Inspiration for the art exhibit “Between Clock and Bed” came to curator Jon Seals ’15 M.A.R. a year ago while he completed his degree at Yale Divinity School and the Institute of Sacred Music. In a seminar on “Worship in the Face of Death,” co-taught by Teresa Berger and Marcus Rathey, Seals discovered the late work of painter Edvard Munch, who endured the loss of numerous family members and turned repeatedly to the theme of mortality in his art. Seals wrote about Munch for the course’s final paper, an essay he later distilled for the proposal and curator’s statement of the exhibit.

The exhibition, on display through June 2 in the Sterling Divinity Quad’s Sarah Smith Gallery and ground-floor corridors, is presented by the ISM with support from the Divinity School. It features the work of six artists, Kenny Jensen, Stephen Knudsen, Natalija Mijatovic, Kirsten Moran, Laura Mosquera, and Ronnie Rysz, each of whom echoes Munch’s preoccupation with mortal limits. Very different artists whose work spans a variety of media and styles, the six were brought together by Seals in part to further examine his own meditations on death, life, and the afterlife. The resulting show is intellectually complex and intimately personal. “It’s a much better exhibit than it was a research paper,” says Seals wryly.

While preparing the paper, Seals uncovered a lesser-known Munch painting, his “Self-Portrait Between the Clock and the Bed,” completed months before his death in 1944 at age 80. Unlike the amplified angst of “The Scream,” the Norwegian artist’s most famous work, “Between the Clock and the Bed” is a sober reflection on impermanence and eternity. The artist stands rigidly before the viewer, hands limp by his side, his face a mask of reluctant acquiescence. He has turned his back on his artist’s studio and its sunrise-yellow walls crowded with paintings—the splendor and fruits of this world—and hovers with a looming grandfather clock to his right and a metal-frame bed to his left.

Seals reads both objects as symbols of death, and Munch, pinned between them, is a fraught figure in a liminal space. It’s a space that Seals is never far from himself, and one he has permanently inscribed on his being in the form of twin tattoos. On his left wrist is a set of four inked digits, 1514, and on his right, in matching block style, another four, 0748. The first number signifies, using 24-hour notation, the exact moment Seals’s three-year-old son Leo was born, at 3:14 in the afternoon on November 30, 2012. The other represents the time recorded on the death certificate of his brother David, killed in a motorcycle accident in 2006. David was 20; Jon, 25, and anyone who knows the elder brother has observed how the loss is imprinted on his gentle and generous nature. “Almost everything I do has something to do with losing my brother,” he says quietly.

Seals acquired the ink not long after David’s death, as homage and memento mori. “David is my right hand,” he says. His brother’s presence on Seals’s arm is a constant reminder of the precariousness of life. “There’s an urgency—I may never breathe again,” he says of the tattoo’s meaning. Further, the unyielding numbers also issue a challenge to strive towards work of enduring value.

Seals acquired the ink not long after David’s death, as homage and memento mori. “David is my right hand,” he says. His brother’s presence on Seals’s arm is a constant reminder of the precariousness of life. “There’s an urgency—I may never breathe again,” he says of the tattoo’s meaning. Further, the unyielding numbers also issue a challenge to strive towards work of enduring value.

“I wanted something to stop me in my tracks when I was making art,” says Seals, who also holds an M.F.A. in painting from the Savannah College of Art and Design. His brother’s tattoo keeps the painter-curator focused on the theological import of his efforts. “What you make with your hands has consequence, in this life and the next. If your gift is a spiritual gift, it does not die in the flesh, it goes on to the next life. We are called to be co-creators. How are you applying those gifts in this life?”

While the signature of his brother’s passing underscores for Seals our short-lived existence, its counterpart on the opposite wrist celebrates the hope of new life. “As artists, that’s where we all are. We live between these two times,” he says.

The exhibition exploits the friction between the opposing and linked states of being and non-being. The double-wide passage of the Sarah Smith Gallery presents a showcase for work by all the artists, while down the length of the corridor off the Divinity School’s main entrance, each participant is presented in what amount to a half-dozen compact solo exhibits. The artists work in oils, acrylics, video, photography, found objects, and pen and ink; they live in places as disparate as the swamps of Florida’s west coast; Savannah, Georgia; upstate New York; New York City; and New Haven. Each has been connected to Seals’s life in the decade since his brother died—at art school, at Yale, and in Florida, where he lives now with his wife and son and teaches art at Southeastern University.

Psychically, the art ranges over even vaster territory. Kirsten Moran’s oil paintings concern what she calls “our ancient ancestral roots” of matriarchy and “the burden and the joy of mortality’s certitude.” In both her monumental portraits of women and her smaller atmospheric abstractions, the passage of time lies exposed on the surface of the canvas. Moran’s brushstrokes, drips, washes, and translucent layers of paint read like palimpsests of finitude, minor-key sonatas. Beside them, Seals has juxtaposed the garish discord of Laura Mosquera’s acrylic paintings in raucous exchange.

“They tumble down the stairs,” Seals says of the free-jazz exuberance of Mosquera’s geometric studies. Her colors seem to advance and recede all at once, setting the eye off-kilter, as do the lines and edges, which are both sharp and unfinished. “These works are meant to rebuke the notion of an end,” the artist writes, “celebrating what still is, while remaining aware that nothing is infinite. Without that knowledge, joy would be hollow.”

Just as Seals places Moran’s and Mosquera’s paintings in conversation, so he does with Stephen Knudsen’s video and painting installation “Game of Waste,” Ronnie Rysz’s portrait drawings, and the photo-collages of Kenny Jensen’s “Layered Histories,” all of which deal with our harsh legacy of devastation and loss. Knudsen’s 90-second looped video of a hunter walking through a woodland confronts not only the fact that we all die, but that we are also the world’s most advanced killers. This predatory legacy is underscored by Knudsen’s discomfiting canvases depicting corpses of dead deer, painted in disarmingly lovely sunset colors.

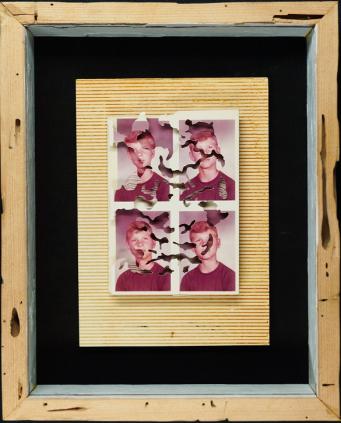

Beside Knudsen hangs Rysz’s equally disturbing portraits made in response to the schoolroom massacre at Sandy Hook, Connecticut. The artist connects that mass killing to the horror of warfare, channeling Goya, the German Expressionists, and the Picasso of Guernica to create two-faced grotesqueries which, like the gunman who killed 20 six- and seven-year-olds, exist in our perception as part human and part monster. The way we make meaning of people and events is the subject of Jensen’s photo-collages as well. On anonymous school portraits salvaged from abandoned photo albums, Jensen has cut away intricate grooves and channels that deface and redefine the images. These cut-outs mimic the patterns of termites as they devour their way through rural Florida, where the artist works. They also evoke the fugitive state of memory and how time alters the past.

Beside Knudsen hangs Rysz’s equally disturbing portraits made in response to the schoolroom massacre at Sandy Hook, Connecticut. The artist connects that mass killing to the horror of warfare, channeling Goya, the German Expressionists, and the Picasso of Guernica to create two-faced grotesqueries which, like the gunman who killed 20 six- and seven-year-olds, exist in our perception as part human and part monster. The way we make meaning of people and events is the subject of Jensen’s photo-collages as well. On anonymous school portraits salvaged from abandoned photo albums, Jensen has cut away intricate grooves and channels that deface and redefine the images. These cut-outs mimic the patterns of termites as they devour their way through rural Florida, where the artist works. They also evoke the fugitive state of memory and how time alters the past.

“These delicate forms are a record of destruction left in the wake of life,” writes Jensen in his statement. His motif of “layered histories” is shared by the exhibition’s sixth artist, Natalija Mijatovic, whose brooding, elegiac paintings are perhaps closest to Munch’s own ethos of loss. Mijatovic was born in Belgrade, Serbia, and experienced the ethnic wars of the 1990s that laid waste to the Balkans. “I remember my previous life as a wintery silence of an empty city, ashes of the burnt home, and snow,” she writes, continuing, “my recurrent interest [is] stillness defined by the … void of human presence.”

Mijatovic’s paintings hint at recognizable objects obscured by time and ruin. Her somber palette of soft grays is built up in layers of thin glazes polished to a lustrous patina. The paintings’ ambiguity between surface and depth, fragility and permanence, physical and metaphysical, mirrors our mortal condition of body and soul.

Speaking of Mijatovic’s paintings, Seals expressed the “wonder and awe” he feels whenever he examines them. The same can be said for the experience of “Between Clock and Bed” as a whole. The closer one looks, the more the exhibition reveals.

Timothy Cahill is an M.A.R. candidate in religion and literature (2016) at the Institute of Sacred Music and Yale Divinity School. A past fellow of the National Arts Journalism Program at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, he served as photography critic and arts correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor and founded the Center for Documentary Arts in upstate New York.