By Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R.

The idea for “The Complexities of Unity,” the current art exhibit at the Yale Divinity School, grew out of last year’s presidential campaign. Idea? It was more like an imperative, as curator Jon Seals ‘15 M.A.R. describes it. He conceived the show last summer during the primaries, well before the shock and awe of the general election. A resident of the swing state of Florida, Jon was swamped by the fractious tone of the public discourse. “We are such a divided country in every way, and I was struck by the irony of the idea, ‘united we stand.’ What does that even mean anymore? Whose unity?”

With works that are expressive, extroverted, and sometimes jarring, the exhibition that grew out of these questions explores principles of harmony and dissonance and ponders the creative tension between order and disorder. The show, sponsored by the Institute of Sacred Music, begins in the Divinity School’s Sarah Smith Gallery and fills the length of the corridor down to the Great Hall in the ISM. It remains on view through June 13.

Jon studied art and religion in the ISM and holds an M.F.A. in painting from the Savannah College of Art and Design.

While at YDS, he continued to make art, once contributing his painting process to the liturgy in Marquand Chapel by working on a canvas during worship. He later added curation to his portfolio, organizing three previous exhibitions at the school, two while a student and a third after graduation.

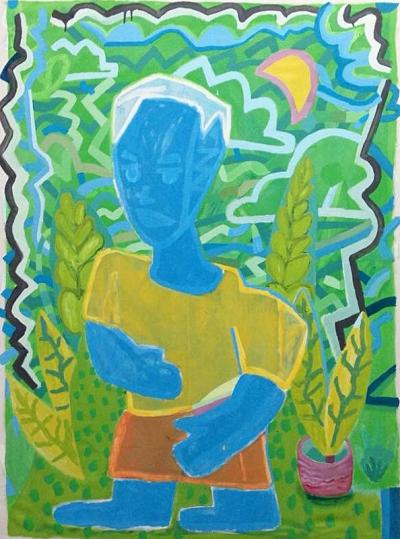

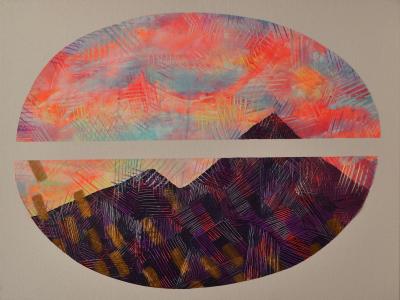

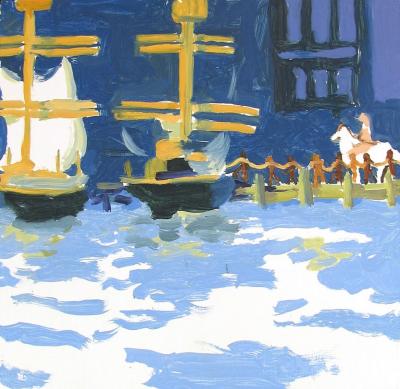

The exhibit features the work of six painters representing a vast diversity of identity, geography, and sensibility. Lily Kuonen is an Arkansas native whose bright landscapes explore juxtapositions of texture and pattern, boundary and passage, and how opposing energies collide and merge. Similarly, Jane Winfield, born in Seattle and now living in Richmond, Va., creates abstractions that blur the line between volume and surface, presence and paint. Jeremy Wright grew up in the surf culture of San Diego, and his multi-panel, collaged paintings display the taut balance required to ride a wave—of ocean or inspiration. Puerto Rico-born Edgard Rodriguez writes that his muscular and tender canvases reflect “the ongoing argument between death and life, ugliness and beauty.” Esteban Cabeza de Baca is from the border town of San Ysidro, Calif. His work addresses the history of his Native American heritage in bright, soft hues that belie the horrors they reveal. New Haven artist Noé Jimenez similarly seduces and subverts. His small abstractions are chromatically seductive, but his portraits are tinged with existential angst.

The exhibit features the work of six painters representing a vast diversity of identity, geography, and sensibility. Lily Kuonen is an Arkansas native whose bright landscapes explore juxtapositions of texture and pattern, boundary and passage, and how opposing energies collide and merge. Similarly, Jane Winfield, born in Seattle and now living in Richmond, Va., creates abstractions that blur the line between volume and surface, presence and paint. Jeremy Wright grew up in the surf culture of San Diego, and his multi-panel, collaged paintings display the taut balance required to ride a wave—of ocean or inspiration. Puerto Rico-born Edgard Rodriguez writes that his muscular and tender canvases reflect “the ongoing argument between death and life, ugliness and beauty.” Esteban Cabeza de Baca is from the border town of San Ysidro, Calif. His work addresses the history of his Native American heritage in bright, soft hues that belie the horrors they reveal. New Haven artist Noé Jimenez similarly seduces and subverts. His small abstractions are chromatically seductive, but his portraits are tinged with existential angst.

For the curator, the exhibit became a vehicle to address the turmoil of the election and its aftermath. Jon is a Kentucky native and works now as Director of Fine Arts at Calvary Christian High School in Clearwater, Fla. A “red state” Southerner, he has his share of ‘blue state” in him too, thanks in part to his time in New Haven. The complexity of influences exposed him to rifts both internally and among family and friends. “The electoral process revealed and magnified things so many of us were unaware of,” he said. “The sense of disunity as it developed over the political year is still right in front of us. We can’t escape it.”

In his curator’s statement, Jon writes, “From this diverse collection of artists’ work, viewers may become artists themselves as they seek to find a harmonious sense of unity within the boundaries of the exhibition space and possibly build upon their own strategies of reconciliation beyond those boundaries, into the urgent social, political, and spiritual realities of our time.”

I met Jon in August 2013, on the first day of BTFO, the “Before the Fall Orientation” at YDS. He introduced himself amid the milling crowd of our incoming class, saying that someone had pointed me out as having once been an art critic. We found an instant rapport. In the several courses we took together, I was always impressed by Jon’s searching and sensitive intelligence, the way he saw things simultaneously from his heart and head. His gentleness of spirit made his intellectual courage all the more compelling.

Having been asked to write about Jon’s new exhibit, I took the opportunity to continue our four-year conversation about art, faith, and the surprising unities of complexity. In the interview below, he describes his vision of his new exhibition, the ways he uses art to unravel the mysteries of life, and how his YDS education continues to shape his thought and practice. For purposes of clarity and compression, the interview has been redacted by me with Jon’s input.

Jon Seals: And then the election happens, and things are so upside down I can’t even bear to watch the media, so where do you go? You go to your friends and family. And you realize there are really difficult conversations to be had at Thanksgiving and Christmas. This is not some abstracted “us-vs-them,” this is your family and friends, these are people you love. This electoral process revealed and magnified the condition of things that so many of us were unaware of, or perhaps just chose not to engage.

Jon Seals: And then the election happens, and things are so upside down I can’t even bear to watch the media, so where do you go? You go to your friends and family. And you realize there are really difficult conversations to be had at Thanksgiving and Christmas. This is not some abstracted “us-vs-them,” this is your family and friends, these are people you love. This electoral process revealed and magnified the condition of things that so many of us were unaware of, or perhaps just chose not to engage.

Timothy Cahill: So that’s the genesis of the exhibit, the sense of unity and disunity as it developed over the political year?

But I didn’t want to do a show that had a bunch of political slogans. The agenda of this show is to explore how complicated unity really can be. In a work of art, too much unity can be boring. A two-dimensional piece that is too unified might become dull. On the other hand, if a piece is too chaotic, and if it’s not pulled together somehow just enough, it may never hold an audience long enough to be considered. Artists dealing with unity in our contemporary art time have to toe a line. They have to give unity its chance to harmonize a piece, but they also have to not go too far, because you need that tension. There are, of course, other ways around this, perhaps a body of work intentionally filled with discord, meant to offset or react to a body of work perceived as too unified or easy to take in. Either way, striking the right amount of tension is necessary.

How does that tension manifest in this exhibit?

There are lots of connections to edges and borders in the exhibit that speak to this tension. Who’s in, who’s out? The breaking of boundaries. Edges are incredibly important visually. Is an edge soft? Is it a hard edge? Is it feathered? Is it spray-painted? Not just the materials, but the processes by which artists are creating edges and boundaries. When I thinking about this work, I learn lessons about how to stand with those who I disagree with.

What kind of lessons? What have you learned?

What kind of lessons? What have you learned?

My first response to politics in the U.S. is just to throw up my hands and bury my head in the sand. After dealing with this work for a while, I’m thinking there can be productivity amidst the differences and amidst the challenges. Those hard boundaries and those soft edges could maybe work together to create something that is compelling, interesting, dynamic. I suppose I’m becoming a little bit more willing to engage in meaningful conversations after seeing this body of work.

That’s a big statement, granting these artworks that kind of influence and potency.

That’s true. It’s a little bit easier for me to voice the idea when I talk about it in visual-art terms. It’s harder to have a conversation, because you’re trying to stay away from buzzwords and avoid all the little catches. I’ve noticed that. Folks who are watching the news every day pick up on the language the talking heads use. It can almost be impossible to have meaningful conversations, because it’s just a bunch of catch-phrases bouncing in the room. Sometimes a really good way to talk about something is to not directly address it, but to use parallels and some other language, some other shop talk, but really you’re also commenting on what has to be dealt with. I can talk art language and have it really be about the politics. I hate even using the word politics. I really don’t want to use that word. I’m heartbroken right now, and it’s not some abstraction. It’s everyone, not just me engaging with my friends and my family—everybody’s having to do that. And if they’re not, maybe they should be. If everyone within your sphere of influence is in agreement, that’s too much unity. That can get pretty ugly. You need some complexity in that. You need some tension.

It’s like my Facebook feed. Somedays I think, please, spare me from my Facebook feed, where everybody hates Trump! They’re apoplectic. “He has to be impeached before Christmas!” Some days I’m in total agreement, but on others it’s too much.

It’s like my Facebook feed. Somedays I think, please, spare me from my Facebook feed, where everybody hates Trump! They’re apoplectic. “He has to be impeached before Christmas!” Some days I’m in total agreement, but on others it’s too much.

My newsfeed is like the United States. It’s like Florida. It’s divided almost down-the-middle.

You’re a Southerner, so you’re connected to a lot more people with divergent political views.

That’s what got my head spinning. These are people I love and care about who have very, very different opinions. What am I going to do about that? I don’t feel qualified to speak directly into this thing. I know everybody’s supposed to have a voice and all that, but that’s not my nature for this topic. But now it’s like, “OK, I have to talk, I have to contribute.” So, I did what I do with everything else. Do an art show about it. Get some artists together and have them talk about the matter, see if I can learn something from them. And I have.

Yet there is no overt political content in the exhibit. Even the artist statements are largely apolitical, in the sense they speak much more from a biographical or formal or theoretical perspective. There’s a lot of art school in the statements, but not a lot of politics.

That’s right. And I wanted it that way.

Your curator’s statement is also mostly devoid of anything—

Your curator’s statement is also mostly devoid of anything—

Only until the last sentence, “into the urgent political issues of our time.”

Yes.

And that was very intentional. Right now, it’s in vogue to make art and do shows that are overtly political.

Yes, to be transgressive, confrontational, resistant. …

This is more of a subtle, intimate, reflective exhibition.

What are the artworks metaphors of, then?

It’s like looking under a microscope. What we’re doing is looking at life, at cell divisions, synapses, the exchange of substances and ideas. Some things are nutrient, and some are excrement and need to be expelled. But even that, I want always to be reverent towards people who disagree with me. So, here’s the work. Think about edges, think about boundaries, think about the nature of life.

Did you talk to the artists about your political concept of the show?

Yes, and it connected with them. They see the tensions in the United States that are exposing the fibers. During the election, both parties struggled with division and direction. I want to be clear, I’m not saying we should just normalize Trump’s language or outrageous behavior. I’m not saying that at all. What’s wrong is wrong. I’m not trying to normalize that. What I am trying to say is, on matters of policies or perspective, in many ways we’ve lost the capacity for dialogue.

That’s a good word, dialogue. The give and take of the community. I know I have nothing in common politically with many—maybe most—of the people I take Communion with on Sunday. And yet we’re there as a community. There’s something that binds us and bridges our differences.

That’s a good word, dialogue. The give and take of the community. I know I have nothing in common politically with many—maybe most—of the people I take Communion with on Sunday. And yet we’re there as a community. There’s something that binds us and bridges our differences.

Yes, that’s great. Exactly right. And that brings us to YDS. Why do a show like this here? Because YDS is really doing a good job with bringing people who are different together and finding commonalities, celebrating differences in healthy ways and building bridges. I can speak into that here. I like doing shows for the ISM because there are people in all camps and ideologies at YDS, yet we all share an agenda to go out and make the world better through service. It’s intellectually rigorous here, and there are people who know enough of the language of art and who can talk about faith, so it’s a unique setting to present these ideas.

How did your education here change you? You already had a highly developed artistic sense. You were already thinking in a dynamic, questioning way. What was it for you about being here?

It was about zooming out and seeing a bigger picture. I was introduced to a bigger world, a more diverse group of people. When you’re in one corner too long, you start to get closed off. Being here, being in ISM, opened me up to people to my left and my right. It opened me to thinking globally and tp public works, public art, dealing not just with the personal issues that everyone carries, but with compassion and outward care toward others. There’s a sense of limitlessness here. Everybody works really hard. And it’s not just the teachers, the professors, who push you to think bigger. Sometimes even the architecture makes you want to do better. When you’re studying in the Div Library’s Day Mission Room, surrounded by books, even the walls kind of say, “Keep going.” There’s a history here and it’s bigger than you. You’re just contributing. And what are you contributing? That atmosphere changes you.

There’s a feeling at Yale like there are no locked doors. Everything can be opened if you find the right combination, the right key. If you apply yourself, you can walk through. It’s not blind permission or privilege. The professors sober you up pretty quick when those first papers come back! … I’ve kept those papers. I have an envelope on my desk, and I’ve told [my wife] if anything ever happens to me, give it to Leo [their four-year-old son] to read later. Many of the things in that envelope are papers that I wrote here, including papers where I was very bluntly criticized.

There’s a feeling at Yale like there are no locked doors. Everything can be opened if you find the right combination, the right key. If you apply yourself, you can walk through. It’s not blind permission or privilege. The professors sober you up pretty quick when those first papers come back! … I’ve kept those papers. I have an envelope on my desk, and I’ve told [my wife] if anything ever happens to me, give it to Leo [their four-year-old son] to read later. Many of the things in that envelope are papers that I wrote here, including papers where I was very bluntly criticized.

At the high school where you work, you’ve developed a guest artist series inspired by ISM Colloquium, where you bring artists together with the school community and the public to talk about art, life, and faith. What’s your perspective on the intersection of art and faith?

It’s symbiotic. They are different languages expressing similar truths. If you’re a person of faith and you’re making art, you really can’t make it without your faith coming into the work in some way, shape, or form, obvious, subtle, subconscious—whatever. You really can’t separate those two things if you start from the position of faith. And then, sometimes, if you’re not a person of faith, you can find spiritual truths in your art practice that may lead you on a path toward revelation, toward growing in faith.

Do you see what you do as ministry in any sense?

I think of ministry as service, and I think I’m serving artists by giving them a place to exhibit. And I’m serving the community here by challenging them with compelling work. Finally, it’s a service to myself [chuckles]. I’m getting to hang out with artists, to listen to them and talk with them.

It’s about bringing people together.

Yes, and that’s so much fun. My grandmother had a saying. I remember as a child going to her house in Kentucky, and she had all these cats, like twenty feral cats. These were not cats you pet. These were wild creatures. Clawing at each other, hissing. They were scary. And I remember asking her, “Mamaw, how do you take care of all these cats?” And she said, “You gotta put the milk out.” There they were yowling at each other, fighting and clawing, and she put the milk bowl out and these cats would all kneel before that bowl, one next to another, and drink substance, they’d drink life, in harmony with one another. You have to put the milk out. That’s what I hope this exhibition can do.

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. is a writer specializing in religion and the arts.