By Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R.

Earlier this year, Michael Peppard ‘03 M.A.R. published an op-ed article in the Sunday New York Times proposing that the Yale University Art Gallery may be home to the earliest verifiable picture of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The article’s provocative headline, “Is This the Oldest Image of the Virgin Mary?” upended decades of certainty about the painting, one of a group of wall paintings from the world’s oldest Christian church.

The image is on permanent exhibit in the Yale Art Gallery’s Ancient Art collection, part of an installation of artifacts taken from a third-century military outpost known as Dura-Europos, in eastern Syria. Before Peppard’s article, it might have been overlooked amid the display, a modest, brownish scene of a lone woman drawing water from a well and looking up with a questioning gaze. It was discovered in the 1930s as part of the excavation of the Syrian site by Yale archeologists, and for 80 years has been identified by scholars as the Samaritan woman at the well from the Gospel of John.

Now Peppard has questioned that designation, and claims that our earliest picture of the Virgin has been hiding in plain sight in the Dura-Europos gallery. His theory has attracted worldwide attention, altering the conversation about Christian art and ritual on the eastern edge of the Roman Empire, while establishing Peppard as a scholar of rising authority.

Peppard, an associate professor in the Department of Theology at Fordham University, made his findings using the same scholarly detective work all academics use. But the questions he asks and the possibilities they yield are more audacious than most.

The intellectual boldness of Peppard’s work marks him as a rising star not just in his specialized field, but across the academy and beyond. At age 39, he has forged twin careers as both a respected scholar and a public intellectual. In the popular media, Peppard has written articles and opinions on topics ranging from the destruction of holy sites by ISIS to Pope Francis’s political leanings, from gay marriage to the NRA. He frequently appears as a religious expert on MSNBC, CNN, PBS, and other networks, and is a contributing editor for the Catholic journal Commonweal. In 2014, he was in the national spotlight when the media sought him out to judge the veracity of a sensational papyrus fragment whose ancient inscriptions proclaimed that Jesus was married.

‘Exceptional gifts’

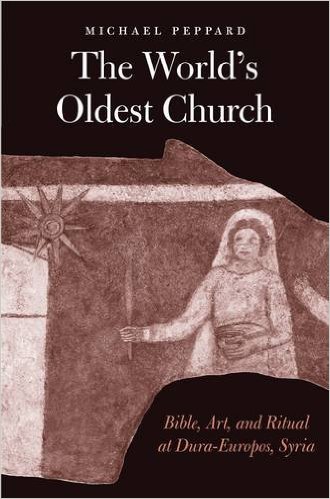

Peppard’s academic career is distinguished by an ever-rising curve. He is tenured at Fordham, where he also serves as an associate director at the Curran Center for American Catholic Studies. He has authored numerous scholarly articles, addresses, and reviews, and his 2011 book, The Son of God in the Roman World: Divine Sonship in its Social and Political Context, offers fresh, sometimes-controversial readings of Christian scripture and early texts. The book won the Manfred Lautenschlaeger Award for Theological Promise from the University of Heidelberg.

Peppard earned a double B.A. in philosophy and theology from Notre Dame, where he studied New Testament with Greg Sterling, now Dean of Yale Divinity School. One class was a rigorous graduate-level seminar that required the undergraduate to get special permission to enroll. Then-professor Sterling did not regret granting it.

“Michael more than held his own against the graduate students,” Sterling reports. “He has exceptional gifts intellectually.”

After a slightly circuitous route, Peppard came eventually to YDS and the Yale Institute of Sacred Music. He received his Master’s magna cum laude in Bible and remained at Yale for a Ph.D. in Religious Studies. At the Divinity School, he was part of an exceptional group of peers who included Timothy Luckritz Marquis ‘02 M.A.R. and Candida Moss ‘02 M.A.R.. All three studied with Harold Attridge, Sterling Professor of Divinity, who recalls that Peppard possessed “a certain independence … a willingness to take risks that has served him well.”

Peppard is not afraid to introduce scholarly imagination, one might even say artistry, into his research. A full account of his work on the woman at the well appears in his book, The World’s Oldest Church: Bible, Art, and Ritual at Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale, 2016). The book reassesses the church’s numerous wall paintings and reinterprets their theological meaning. To animate his narrative, Peppard introduces an imagined character, a Christian initiate called Isseos the Neophyte, who moves through the house-church encountering its art in the various rooms. A painting in the baptistry contains a procession of veiled women, an image scholars have long held represents the women at Christ’s tomb. Peppard demurs, asserting instead that it depicts a wedding procession. If he is right, the image suggests that initiation rituals at Dura did not embody symbolic death and resurrection, a theology of baptism extending back to Saint Paul. Instead, Peppard wrote in the Times, the Syrian paintings “[celebrate] salvation through images of marriage, pregnancy, and birth.”

Peppard is not afraid to introduce scholarly imagination, one might even say artistry, into his research. A full account of his work on the woman at the well appears in his book, The World’s Oldest Church: Bible, Art, and Ritual at Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale, 2016). The book reassesses the church’s numerous wall paintings and reinterprets their theological meaning. To animate his narrative, Peppard introduces an imagined character, a Christian initiate called Isseos the Neophyte, who moves through the house-church encountering its art in the various rooms. A painting in the baptistry contains a procession of veiled women, an image scholars have long held represents the women at Christ’s tomb. Peppard demurs, asserting instead that it depicts a wedding procession. If he is right, the image suggests that initiation rituals at Dura did not embody symbolic death and resurrection, a theology of baptism extending back to Saint Paul. Instead, Peppard wrote in the Times, the Syrian paintings “[celebrate] salvation through images of marriage, pregnancy, and birth.”

Self-discovery

Peppard said writing the Dura book was as much an act of self-discovery as of scholarly expression. He discussed his process last month in an interview at the Yale Art Gallery. Typical of his dual roles in the academy and the public square, he was in New Haven to deliver a paper at a liturgy conference at the ISM and to meet a CBS News crew filming a program on his Dura findings.

“I learned about myself through this process” of writing, he said in the interview. “I learned that my interest and my method were going to be a little more imaginative, a little bit more provocative—not in the sense of controversy, but in the sense of provoking both the field of religion and art history to ask more questions about the evidence we thought we had covered really well.”

Nowhere is this challenge to received opinion more evident than in his work on the woman at the well. Peppard is skeptical that the image represents the Samaritan divorcee who offers Jesus water in John 4, because all known depictions of the episode include both the woman and Christ, never her alone. He sees the painting as a visualization of the Annunciation, but not the familiar one from Luke’s Gospel and Renaissance scenes where Gabriel appears to a Mary seated indoors, reading scripture or at prayer. Peppard draws instead from an Annunciation story described in a venerable Syrian “biography” of Mary, which places the moment when “an angelic visitor informed [the Virgin] of her miraculous pregnancy” beside a well or spring, where she had gone to fetch water.

In this textual tradition, the angel hails Mary as a disembodied presence, a voice in thin air. She is startled, hesitant, confused, as the woman in the Dura painting appears. Across centuries of Christian art, Peppard traced a lineage of visual representations of this alternate Annunciation, all set around water. He then reexamined the excavation field notes from the 1930s and discovered clues to the woman’s identity that are no longer visible on the painting. From this evidence, Peppard arrived at his conclusion that the image depicts the Virgin.

“I had to convince myself for quite a while, because [identifying the woman as Mary] seemed a little crazy to me,” Peppard admitted. “Why would everyone have thought it was something else? Am I really a better interpreter of ancient art than all these experts who have looked at it before?”

‘Angry’

A more conservative scholar might have shied away from answering that question in the affirmative and risking the likely ridicule. An episode from Peppard’s past helps explain where he gets his daring.

A more conservative scholar might have shied away from answering that question in the affirmative and risking the likely ridicule. An episode from Peppard’s past helps explain where he gets his daring.

It happened after his sophomore year at Notre Dame, where—inscrutably, for someone who knows him only as a religion scholar—he had completed two years of study in chemical engineering. That summer, Peppard toured Europe with the university glee club, viewing cathedrals and historic sites, relics and masterpieces. The trip ended in Rome, where a friend gave Peppard a hard-to-come-by ticket to the Vatican Necropolis, beneath Saint Peter’s Basilica. The ancient crypt, said to contain the tomb of the apostle Peter, is only accessible by special arrangement to small groups.

As he wandered the paths among the ancient monuments and sepulchers, Peppard experienced predictable waves of admiration and awe. But he was also charged by a darker and more clarifying emotion.

“I was spiritually uplifted and all that,” Peppard remembers, “but primarily I was angry. Everywhere I’m seeing Greek and Latin and symbols I didn’t know … and artistic imagery I didn’t know how to interpret. I [became] angry at my education and my upbringing. My history of Christianity was Jesus, Paul, Augustine, the Dark Ages, Luther, C.S. Lewis. Honestly, that was my time line. [Now] here’s a whole world that nobody ever showed me. These are my people and I don’t know what they’re saying. These Christians in these tombs, I’m in a lineage with them. I had all this Christianity in my life, but no way of interpreting what I was looking at. It made me mad.”

Almost on the spot, Peppard scrapped engineering and decided to pursue a dual degree in philosophy and theology. He completed the double major in just four semesters and graduated with his class.

The same passionate resolve he had as a student informs who Peppard is now as a scholar and writer. When he speaks of a colleague, the interdisciplinary historian Peter Brown, he describes his own ethos as well.

“Interdisciplinary scholarship … tends toward the bold, toward synthesizing,” he said. “When you bring two fields together, you necessarily innovate with a method and you see new things…. Are all [the] arguments open and shut? No. They … characterize a world that invites in the reader—there’s no way you could agree with every sentence in there, because that’s not the style of scholar he is.”

The scholarly world has yet to offer formal comment on Peppard’s Mary findings. But the Yale Art Gallery considered his claims sufficiently authoritative to incorporate them into the text that accompanies the painting.

—

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. is a writer specializing in religion and the arts.