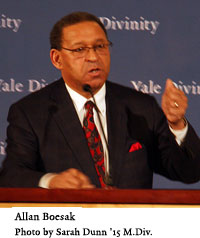

The Rev. Dr. Allan Boesak, a South African liberationist theologian and minister known by many for his leadership against apartheid and for serving as president of the World Alliance of Reform Churches, is not one to shy away from speaking and preaching the truth of justice and reconciliation. His February visit to YDS was no exception.

As a young minister, just after completing his graduate studies in Europe, Boesak returned to his homeland to find himself at the front of the battle to end apartheid. Along with his activist ministry in Cape Town, Boesak was instrumental in the establishment of the United Democratic Front—one of South Africa’s most important anti-apartheid organizations in the 1980s. Two years before the infamous Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the TRC) in 1995, South African apartheid ended over a three-year period of negotiations in a city called Kempton Park, north east of Johannesburg. Boesak’s lecture, entitled ‘Reconciliation, Justice, and the Spirit of Ubuntu,’ focused on understanding the failings of Kempton Park and the TRC in achieving justice in South Africa.

As a young minister, just after completing his graduate studies in Europe, Boesak returned to his homeland to find himself at the front of the battle to end apartheid. Along with his activist ministry in Cape Town, Boesak was instrumental in the establishment of the United Democratic Front—one of South Africa’s most important anti-apartheid organizations in the 1980s. Two years before the infamous Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the TRC) in 1995, South African apartheid ended over a three-year period of negotiations in a city called Kempton Park, north east of Johannesburg. Boesak’s lecture, entitled ‘Reconciliation, Justice, and the Spirit of Ubuntu,’ focused on understanding the failings of Kempton Park and the TRC in achieving justice in South Africa.

Nearly two decades have past since the Kempton Park negotiations and the TRC, yet, Boesak stressed, social inequality between blacks and whites remain at frighteningly similar to the levels they did during apartheid. The purpose of Boesak’s lecture was to identify why reconciliation in South Africa has failed so catastrophically at resolving issues of social injustice, where the vast majority of the country’s black population remains racially segregated and economically depressed and exploited.

Boesak is highly critical that the TRC had more in common with the logic of apartheid than one might assume. The TRC only addressed the excessive physical, criminal violence that occurred beyond the law (violence that was illegal even under apartheid law), but it ignored the structural and systemic political violence inherent within apartheid law itself. “In words, the TRC upheld rather than questioned the rule of law under apartheid,” said Boesak, “And this has enormous theological, political, and ethical consequences.”

Following the dismantling of apartheid at Kempton Park, the TRC assumed a model of ‘restorative justice,’ which emphasized the personal conversion of the criminal perpetrators of apartheid and their reconciliation with apartheid’s victims. Boesak, however, insists that the individualistic model of restorative justice failed to address both the long-term societal effects apartheid wrought on blacks and the systemic nature of the wrongs done under apartheid law. As a result, Kempton Park and the TRC inadvertently allowed a social predicament to continue that sustains white wealth and privilege on the one hand, and black poverty, humiliation, and deprivation on the other. Though apartheid was defeated, these historic social injustices—injustices the reconciliation process failed to account for—have persisted unambiguously in the present, most visibly in the massacre of Marikana miners last autumn.

In place of the limited model of restorative justice, Boesak insisted a form of “social and distributive justice, so as to make reconciliation authentic, durable, and sustainable.” Boesak developed this alternative model of justice using liberationist thought and the thought of his former mentor, YDS ethicist Nicholas Wolterstorff, the Noah Porter Emeritus Professor of Philosophical Theology at Yale. Social and distributive justice would not only be effective at the personal level of forgiveness between criminals and victims of apartheid, but it would also, perhaps most importantly, effect apartheid’s beneficiaries and survivors on a social, structural, and systemic level of justice.

Since apartheid ended, much attention and praise has been given to the African concept of ‘Ubuntu,’ which identifies essential human worth and interconnectedness. Boesak admitted that Ubuntu is an indisputable resource South Africans have to offer to the world in terms of personal forgiveness—and he credits TRC chair Archbishop Desmond Tutu for exemplifying this dimension. But, Boesak warned, the reconciliatory power of Ubuntu has been romantically overemphasized because it does not “enable the doing of systemic justice or the undoing of systemic injustice.” Justice may be implied in Ubuntu, but it is not demanded. Thus, contrary to the sentiments of many, for Boesak is convinced that Ubuntu is not adequate “to bring about the justice Christians are called to as required by God” because it does not address inequalities between women and men, rich and poor; it does not speak of rights and wrongs, of liberation and oppression.

Rather than relying on Ubuntu, Boesak followed Wolterstorff’s claim, “The coming of justice requires social inversion.” Additionally, this inversion is impossible “without reciprocal sacrificial acts on the part of the beneficiaries of apartheid.” Boesak expressed his dismay about the prospect of such reciprocation and sacrifice being enacted within countries like South Africa and the United States. He identified the “liberal capitalism, with its in-built need for inequalities and exploitation and greed” as the fundamental barrier to justice and reconciliation. In such capitalist countries, where the disparities between rich and poor are higher than anywhere else in the world, Boesak prophetically associated the coming of justice directly with economic inversion of capitalism.

In a later lecture, Boesak drew on his experience in the anti-apartheid movement to speculate on how Christians today can engage in the coming of justice. More than anything, he underlined the need for Christians to speak openly and with moral authority on matters of injustice. Responding to student’s comment about churches’ declining attendance and relevance in the 21st century, Boesak, recalling churches that silently tolerated apartheid, said, “Either the Church speaks with authority, or it loses its authority.”

Near the end of his visit, Boesak expressed how taken he was with the passion YDS students and faculty have for realizing the justice and reconciliation of God’s Kingdom. Likewise, the reception of Boesak by the YDS community was one of enthusiasm. “I love when people have the courage to take on icons, and Ubuntu is definitely an icon in South Africa,” said Leonard Curry (M. Div ’13).

Nora Tubbs Tisdale, Clement-Muehl Professor of Homiletics, said, “I feel like I’ve heard some of the most prophetic witness in my seven years at Yale Divinity School.” In a country and a world with increasingly greater need for prophetic voices like Rev. Boesak’s, it is assuring to know that a spirit of prophetic justice and reconciliation is growing stronger each day at YDS.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 3.26 KB |