By Timothy Cahill ’16 M.A.R.

On a late September Sunday two years ago, some 45 members of the United Church of Christ gathered at the outdoor sanctuary of the Cathedral of the Pines in southern New Hampshire to remember the words of a dying man.

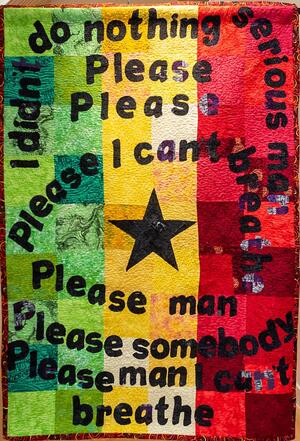

Please man. Please. I can’t breathe.

Four months earlier, on May 25, 2020, America and the world had watched in horror and outrage the public murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Handcuffed and pinned to the pavement, Floyd pleaded for eight minutes and forty-six seconds as his life ebbed away under a policeman’s knee.

How to respond to such brutality? Ten days after the video of Floyd’s death went viral, Rev. Mark Koyama ’15 M.Div. offered UCC churches across New Hampshire an answer. Koyama, pastor of the United Church of Jaffrey, invited congregations statewide to design and stitch quilts based on George Floyd’s last words. Nine churches responded to his “Sacred Ally Quilt Project” and over that summer worked in pandemic isolation to create 10 quilts.

How to respond to such brutality? Ten days after the video of Floyd’s death went viral, Rev. Mark Koyama ’15 M.Div. offered UCC churches across New Hampshire an answer. Koyama, pastor of the United Church of Jaffrey, invited congregations statewide to design and stitch quilts based on George Floyd’s last words. Nine churches responded to his “Sacred Ally Quilt Project” and over that summer worked in pandemic isolation to create 10 quilts.

Now, masked and socially distanced, they’d brought their creations to the open-air cathedral for a service of blessing led by Koyama. The quilts were later displayed in a nearby reception hall, the first time anyone had seen them in one place.

The scene is captured in Stitch, Breathe, Speak: The George Floyd Quilts, a new film that documents the project. The experience of seeing the ten quilts together for the first time, Koyama recalls in the documentary, “was one of those moments where the hair stands up on the back of your neck.”

As the second anniversary of Floyd’s death approached, the UCC minister was experiencing more of the same frisson as the quilts left New Hampshire for New York City. On May 22, Positive Exposure 109, an East Harlem gallery and performance space, unveiled the project and hosted the film’s world premiere. Three days later, on the anniversary of the killing, the quilts were installed for one day only in Manhattan’s Riverside Church, where Koyama was guest preacher at the evening service. From May 26 through June 10, the quilts are back on exhibit at PE 109.

Please, somebody. I can’t move. My neck hurts. Some water or something.

Reflex toward activism

When he preached on May 25 under the Gothic roof of the Riverside Church, Koyama was returning to the place where he worshipped as a teenager in the 1980s. His family lived across the street from the storied edifice while his father, Japanese theologian Kosuke Koyama, taught next door at Union Theological Seminary. Theology superstars like James Cone and Cornell West were neighbors, and at Riverside, Koyama listened to the sermons of Senior Minister, former Yale chaplain, and prototypical radical churchman William Sloane Coffin ’49 B.A., ’56 M.Div. Koyama’s mother participated with the church in protesting the policies of Ronald Reagan, and he remembers meeting Salvadoran refugees given illegal sanctuary in one of the cathedral towers.

“That was definitely where my early reflex toward activism came from,” he said in a recent interview.

It was second nature for Koyama to use a seemingly benign craft art as a hammer against racist violence. “I knew there was a demographic of people in churches in New Hampshire who wanted to be allies but didn’t know how,” he explains in the film. “I felt like [quilting] might be a way.”

The quilts, each four feet wide and between three and six feet long, exploit all the techniques of fabric art, including vibrant colors, diverse textures, expressive needlework, and designs inspired by traditional New England forms, contemporary art, and African aesthetics.

The quilts, each four feet wide and between three and six feet long, exploit all the techniques of fabric art, including vibrant colors, diverse textures, expressive needlework, and designs inspired by traditional New England forms, contemporary art, and African aesthetics.

Stitched in four-inch letters across each surface, Floyd’s words have a searing effect. They evoke the “last seven words” of Jesus, his expressions of pain, abandonment, and entreaty from the cross as recorded in the Gospels. They resonate too with the cries of Black men and women extending back through centuries of American history.

“Those words are the distillation of four hundred years of oppression,” said Koyama.

They gon’ kill me, man. Please. I can’t breathe, officer. Don’t kill me.

Racial justice allies

The agony in Floyd’s last utterances is far too familiar to Sacred Ally quilter Dr. Harriet Ward, who as a Black woman knows the history of racist atrocities.

This ancestral knowledge at first made Ward, a retired cortical-vision scientist, less than sanguine about Koyama’s motives for his project. She is a member of the New Hampshire UCC’s Racial Justice Mission Group, which had to give approval to the quilt proposal.

“I didn’t know [Mark] from Adam, and I immediately didn’t trust him,” admitted Ward during a Zoom interview from her home. “He wanted to know if we would endorse his quilt project. I was initially wary, as were the other two Black women in our conference. We were all a little wary.”

The initial suspicion, Ward makes clear, is a protective reaction by Black Americans toward outbursts of benevolence from the white world, a realm (though Koyama himself is half Japanese) thoroughly embodied by New England congregational churches.

She soon discovered that in the minister she had found a true racial-justice ally, simpatico to her resentment not just toward white cruelty, but white complacency as well.

In the film, Ward makes a haunting observation about Floyd’s dying pleas, as captured on the two quilts she made. “These words?” she said. “Not a current event. I know that the people around me here were looking at [them] as a ‘now,’ but I wasn’t.”

In the film, Ward makes a haunting observation about Floyd’s dying pleas, as captured on the two quilts she made. “These words?” she said. “Not a current event. I know that the people around me here were looking at [them] as a ‘now,’ but I wasn’t.”

A chief goal of the quilts for both Koyama and Ward is battling the white response she calls in the film “outrage and amnesia,” where commitment to reform lasts barely longer than the news cycle. Amplifying her emotion, she said in an interview, “ephemeral outrage—temporary outrage—convenient outrage.”

C’mon man, I cannot breathe. I cannot breathe. They gon’ kill me.

A living exhibit

“Taking the step to sustained concern toward someone who’s not you or your family … requires spiritual transformation,” Koyama said. The quilt project is an attempt, “to take the discernment [of anti-racism action] into the prayerful, to make it not just an intellectual encounter, but a spiritual one.”

The quilts convey a “productive tension between suffering and beauty,” said Koyama. They incite a complex feedback that “is not logos driven, it’s pathos driven. And that’s what liturgy is too when it’s most effective. It uses pathos to open you to being receptive to transformation.”

Harriet has observed, he added, that the quilts preach differently to different groups.

Harriet has observed, he added, that the quilts preach differently to different groups.

“They either implicate you or they include you,” he said. “Whites react to them first through aesthetics, then gradually come to the suffering. Then, they get quiet [and] move more into themselves.” In contrast, “Black audiences get excited by the quilts, take selfies, get up close to them.”

It was Ward who also helped Koyama grasp the deepest truth of his own creation. The quilts’ presence in the world, she told him, constitutes a calling far bigger than the word “project” can contain. More rightly, she said, the quilts should be understood as a sustained service of faith—a ministry.

“Harriet made the case that the quilts should never be in storage,” Koyama explained. “‘If you put them in storage,’ she said, ‘then they’re not alive, they’re not doing their work.’ That was the transition. For me, going into this, it was an expedient way to get people to think more carefully and to be transformed by art. For her, it was a living exhibit that [should] continue and do its work for years to come. It was a completely different way of seeing it.”

At that moment, the effort adopted the name it goes by today, the “Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry.”

Mama, I’m through. Mama. I cannot breathe. They gon’ kill me. Please sir, I can’t breathe. Please. I can’t breathe.

Positive Exposure

The reach of Koyama and Ward’s work expanded dramatically with the debut of the documentary and exhibition. The venue, Positive Exposure 109 on East 109th Street, is high profile, located just north of New York’s famed “Museum Mile” and a block from The Africa Center museum of African art. The gallery was founded 25 years ago by fashion photographer Rick Guidotti to, as the website expresses it, “[impact] human rights, mental health, medicine, and education” through the arts.

Guidotti first collaborated with Ward more than 20 years ago, as part of his work photographing people with albinism, a genetic condition that, among other things, causes blindness. When she described the quilt project to him, Guidotti recalled, “I had goosebumps the whole time she was telling me.” He immediately expressed his enthusiasm to host an exhibition.

“My answer to Harriet will always be yes,” he said.

The documentary Stitch, Breathe, Speak arose from a similar affinity between Koyama and director Chris Owen. The two men had met when the filmmaker interviewed the minister for his “What In God’s Name” podcast in 2019. That conversation was about a similar intervention Koyama had devised with his congregation, the installation of 268 crosses on the lawn of the church to commemorate victims of mass shootings that year.

When Koyama called to pitch a podcast episode about the quilts, Owen said, “I took his offer and raised him to a film.” The 17-minute documentary includes interviews with Koyama, Ward, and other participants about the impact of working on the project, and scenes of people reacting to the finished quilts. An ordained minister himself, Owen sees Stitch, Breathe, Speak as a way to encounter the Divine “during moments of shared public life—how we might see God as present (or not present) in unspeakable suffering.”

Among the film’s most affecting moments has Koyama simply taking a series of deep breaths.

“For me, breath has been central to this whole project,” he tells the camera. “Being created in the image of God is being given breath. This notion that we would deprive each other of that breath is another way of talking about depriving each other to our connection to the holy and to God.”

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. writes about the intersection of faith, ethics, and the arts.