By Lauren Yanks

For over 40 years, Dr. Richard F. Mollica ‘79 M.A.R. has pioneered the field of refugee trauma. In 1981, he opened one of the first clinics in the country for survivors of mass violence and torture. Now called the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, the clinic has helped thousands of people rebuild their lives. But first, there was a lot to learn.

“When we started, there was this idea in psychiatry that victims of extreme violence were beyond help,” said Mollica, recipient of the Divinity School’s Lux et Veritas alumni award for 2023. “So, my team and I were essentially creating a new field.”

“When we started, there was this idea in psychiatry that victims of extreme violence were beyond help,” said Mollica, recipient of the Divinity School’s Lux et Veritas alumni award for 2023. “So, my team and I were essentially creating a new field.”

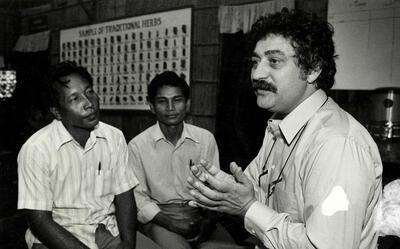

Many of the clinic’s first patients were survivors of the Cambodian genocide.

“We could not believe the stories we heard,” Mollica said. “We didn’t know how to diagnose trauma or torture, especially from another culture. We didn’t have the neuroscience. We were not familiar with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We’ve learned an enormous amount through the years.”

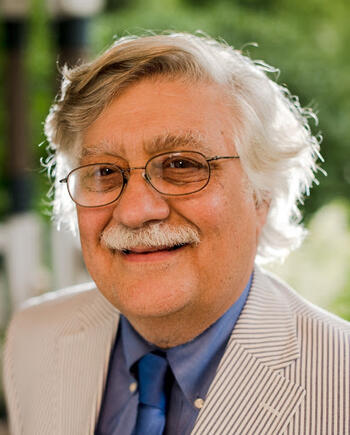

With warm eyes and wavy white hair, Mollica resembles a modern-day Mark Twain. He lives with his wife, a general practitioner specializing in women’s health, in an idyllic setting near Walden Pond in Concord, Mass. A lifelong Catholic who adores Saint Francis, Mollica also considers himself a Transcendentalist.

“The Transcendentalists believed that there’s a spirituality in nature which creates beauty and brings peace, harmony, and goodness to the world,” he said. “And Saint Francis is the Patron Saint of Ecology. I incorporate their ideas into my work.”

A Bronx tale

Mollica has a great fondness for the South Bronx, his childhood home. Neither of his parents finished high school.

“My grandparents were poor Italian immigrants, and my mother’s mother died in childbirth,” he said. “My mother was sent away and raised in a convent. It was traumatic.”

His mother struggled with depression throughout her life but held firm to the Italian tradition.

“She believed in la bella figura, which means that when you do something, you do it the right way, the beautiful way,” said Mollica. “Even if you’re just making raviolis, you need the perfect flour and the perfect cheese. It can take ten hours.”

Mollica’s father also faced tragedy while growing up. At just six years of age, he found his father—Mollica’s grandfather—lying in a pool of blood in front of his vegetable stand.

“My grandfather was murdered by the mafia,” Mollica said. “We don’t know why. There was a lot of violence at this time.”

A few years later, Mollica’s father contracted meningitis and was left legally blind, something he managed to keep to himself.

A few years later, Mollica’s father contracted meningitis and was left legally blind, something he managed to keep to himself.

“I only learned he was legally blind when he came for a checkup at my medical school,” Mollica said. “I couldn’t believe it. I remember my father just laughed and said, ‘Now you know my secret. Don’t tell your mother.’ Till the day she died, my mother never knew.”

Mollica peppers his conversations with his father’s favorite sayings, including, “It doesn’t matter if you are poor, always help others,” and “See reality clearly, but never give up your dream.”

Mollica has done just that. After excelling in math and science at Brooklyn Technical High School, he received a scholarship to Reed College, a liberal arts school in Portland, Oregon.

“It was at Reed that I learned about philosophy and religion, and decided to go to medical school,” he said. “I considered medicine applied religion.”

After medical school in New Mexico and a neurology internship at the University of Toronto, Mollica chose Yale for his psychiatric residency.

“I liked that I could do my residency and go to the Divinity School at the same time,” he said. “Both experiences were life changing.”

Life at Yale

When Mollica started in 1974, he formed a deep bond with Dr. Fritz Redlich, dean of the Yale School of Medicine. Originally from Vienna, Redlich was a psychiatrist who led the famous 1950s study, “Social Class and Mental Illness.” It highlighted the stark disparities in mental healthcare treatment between the rich and the poor, catching the attention of people including President Kennedy.

“JFK read the study, and it influenced his policies,” Mollica said.

Near the end of Mollica’s residency, Redlich asked him to lead a follow-up study. Mollica found that while new mental health clinics spurred by the first study helped dramatically, they were still not reaching people of color.

“I wanted to change that,” Mollica said.

While engaged in his research, Mollica relished his time at YDS. He took a course with the renowned Catholic priest and theologian Henri Nouwen, who gifted him some of his private books.

“He wrote The Wounded Healer, which had a huge impact on me,” said Mollica. “And he introduced me to Thomas Merton’s work on contemplative prayer. I still use both in my work.”

After graduation, Mollica was hired as a psychiatrist at Harvard. He went from the hospital to the medical school, seeing clients and conducting research. Shortly thereafter, he opened his refugee clinic.

After graduation, Mollica was hired as a psychiatrist at Harvard. He went from the hospital to the medical school, seeing clients and conducting research. Shortly thereafter, he opened his refugee clinic.

“My goal was to provide the best medical care to the poorest people,” he said. “And I used my mother’s idea of la bella figura—art and tapestries and plants filled our clinic. It was more beautiful than where the rich people went.”

After a few years of on-the-ground learning, Mollica and his team developed the trauma story.

“We came up with an architecture of the trauma story which is part of a profound healing process,” he said. “People have a need to tell their stories. There’s a beauty to the story because it brings imagination, innovation, and altruism.”

The trauma story

Mollica discusses the four dimensions to the trauma story. The first dimension is the facts. The second is the cultural meaning.

“When working with refugees, it’s important to gain an understanding of their culture,” he said. “You cannot be fully present otherwise.”

The third dimension is what Mollica calls revelation, drawn from Thomas Merton’s work on contemplative prayer and the idea of “looking behind the curtain.”

“When people suffer, they lose their world and everything they believe in,” Mollica said. “They must find the strength to recreate their world, and in that process, they discover the things in their old world that no longer serve them. They acquire wisdom and revelation. Merton called this ‘looking behind the curtain.’ This looking and rebuilding brings new understanding. It also brings virtue and a desire to serve others.”

Mollica shares some of the revelations experienced by the Cambodian women he treated.

“These women were not only liberated from their trauma, but from patriarchy,” he said. “When your whole family is killed, you have to go out and make a living and rearrange the cultural norms. You’re forced to look behind the curtain, and there you find insight and liberation.”

The fourth dimension of the trauma story is the relationship between the storyteller and the listener. Mollica is passionate about deep listening.

“Deep listening is the single most important thing I’ve done in my life,” he said. ”Sometimes I wait 30 years for a patient to tell me the story, but I’m ready for it.”

Mollica seeks to integrate trauma care into primary healthcare, but it is an uphill battle. Most primary physicians, he says, interrupt their patients after around 10 seconds.

“They don’t want to hear a patient’s trauma story because they don’t have the time or training, they’re not paid for it, and it’s upsetting,” Mollica said. “While trauma stories are used in the humanitarian world, the medical world remains wary.”

Lately, Mollica has focused on creating buildings that are healing environments, including ecologically sound homes for trauma victims. Last January, he opened one of these healing structures in Haiti with the help of Father Jean-Charles Wismick, a Haitian priest currently living at the Vatican as head of the Montfort Missionaries Order. The two men met when Wismick, also a psychologist, attended one of Mollica’s trainings.

“There is great trauma in Haiti and much work needs to be done,” Wismick said. “I learned a great deal from Dr. Mollica’s training. He is a wonderful person with a brilliant mind and compassionate heart. He changed my life.”

“There is great trauma in Haiti and much work needs to be done,” Wismick said. “I learned a great deal from Dr. Mollica’s training. He is a wonderful person with a brilliant mind and compassionate heart. He changed my life.”

Shortly thereafter, Mollica visited Wismick in Haiti, and they decided to build together. Their new holistic healing environment includes a family therapy room, a play area for kids, a bird sanctuary, and a garden for peace, meditation, and beauty. They also ask each visitor to plant a tree.

“We educate about the importance of giving back and that people can build their own beauty anywhere,” Wismick said. “As Dr. Mollica believes, there is no healing without beauty.”

The new holistic healing center in Haiti: Watch this brief video.

Born in Sarajevo, Aida Kapetanovic was working as a medical doctor when the Bosnian War broke out. Responding to the crisis, she provided healthcare and psychological support to Bosnian refugees in Croatia.

Kapetanovic met Mollica in 1995 when he and his team traveled to Bosnia to educate healthcare practitioners.

“We discussed philosophy, PTSD and depression, elements of trauma story, and many other things,” she said.

Kapetanovic became the director of the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma in Bosnia for five years, overseeing several projects, including the introduction of mental health teams into primary healthcare.

“With the help of Professor Mollica, it became a model that spread throughout the country,” Kapetanovic said. “He is a great being with enormous strength and heart.”

Mollica is currently writing his second book, New Medicine for a Wounded World from Oxford University Press. Due out next year, it examines the future of mental healthcare interspersed with reflections on his life’s journey. Overall, Mollica expresses profound gratitude for all the people he’s worked with through the years, especially his patients.

“Their courage and wisdom have given me deep insights into the human condition,” he said. “They provide healing not just for themselves, but for the world. This work is truly miraculous. Each patient is a miracle.”

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.