Jathan Martin ’21 M.Div. is the curator of an exhibit titled “I’m Buildin’ Me a Home” on display in the Divinity School’s Sarah Smith Gallery since September. The exhibition uses photos, text, artifacts, and a shelf of seminal books to tell the story of a church tradition that has been an essential source of community, resilience, and dignity for African Americans.

As the exhibit’s three-month run entered its final stretch, Martin sat down with the YDS Communications Office to reflect on the exhibit, the story behind it, and the conversations it has prompted.

What inspired you to create this exhibition?

The exhibit was birthed from my passion for recording and telling the histories of black churches across the United States. My home church in Apalachicola, Florida, pastored by my parents now, was founded in 1946 by my great-great-grandfather. In 2011, our church was burned down by a white teenager. I remember standing in front of the fire, just watching as so many memories burned right along with that building.

The exhibit was birthed from my passion for recording and telling the histories of black churches across the United States. My home church in Apalachicola, Florida, pastored by my parents now, was founded in 1946 by my great-great-grandfather. In 2011, our church was burned down by a white teenager. I remember standing in front of the fire, just watching as so many memories burned right along with that building.

The memorabilia, the records, so many memories— the church was like another home for me. There was no way to get the photos and other artifacts back—they were all destroyed.

From this experience, I recognized the necessity of digitally recording the histories of Black churches and their material artifacts. Black churches continue to burn, so it’s important to maintain their histories and artifacts in some way.

How have exhibit visitors been responding—what kinds of conversations has it evoked?

I was blessed to receive an email from an 86-year-old African American man in New Haven that reminded me that this work is not unique to me. This particular man—he’s a member of the Dixwell Avenue Congregational UCC—has been doing this work over the span of his life. The interaction helped me realize that I have taken up a worthy mantle by recording Black church histories, and quite possibly, folks after me will use my work as they continue to record and tell these stories.

***

Jathan Martin’s project team includes Amina Shumake ’21 M.Div., Martine Bruno ’21 M.Div., Jyrekis Collins ’22 M.Div., Naja Grasty, Neil Grasty, Josh Huber ’22 M.Div., and Jalen Parks ’22 M.Div. Learn more about them and the exhibit by visiting buildinmeahome.com.

***

Beyond the practical considerations, why did you and your team make New Haven such a strong focus of the exhibition?

New Haven has a rich African American history. The city was a stop on the Underground Railroad, including some of the churches that are part of the exhibit. New Haven was where much of the Amistad history took place. The famous Black Panther trials were here. Those are just a few examples …

The city also has a rich and diverse history of African American churches, ranging from the first Black church in New Haven—Varick Memorial AME Zion Church—to the UCC churches, the other AME churches, the Baptist churches, and the Pentecostal churches. By looking at New Haven, you get a glimpse of what Black churches look like nationally. So the city was the best scene for the story we wanted to tell about the history of the Black Church.

The city also has a rich and diverse history of African American churches, ranging from the first Black church in New Haven—Varick Memorial AME Zion Church—to the UCC churches, the other AME churches, the Baptist churches, and the Pentecostal churches. By looking at New Haven, you get a glimpse of what Black churches look like nationally. So the city was the best scene for the story we wanted to tell about the history of the Black Church.

How do you describe the role that Black churches have played in the United States, historically and today?

From its inception through the present moment, the Black Church has been an epicenter of Black life. From the hush arbors during chattel slavery to the brick-and-mortar churches that followed, the Black Church has attended to the social, economic, spiritual, and mental needs of the Black community.

But the Black Church, like all institutions, has its ills. For example, women make up the majority of the people at these churches, but our pulpits don’t reflect that. We know that in many churches queer folks have to hide their identities to ensure their safety. These have caused ruptures, unfortunately.

But the beautiful thing for me is the way the ruptures have caused other spaces of sacredness to form. I’m thinking about things like the ballroom scene as a sacred space, or the beauty salon or the barbershop—spaces that in so many ways mirror the social life birthed in Black churches and that create another home, another haven, for Black life to come to its fullness. As I expand my work in the future, I’m interested in looking at other secular sacred spaces and the ways they’ve provided a spiritual haven outside of what we understand to be the Black Church.

Definitely. I had the opportunity to partake in protests over the summer here in New Haven. At times I felt I was in church. The call-and-response was reminiscent of what I grew up with in the Pentecostal tradition. The speaker would call out “No Justice!” and the protesters would shout back “No Peace!” The chants, the hugs, the words all made it feel like a church space for me.

It’s clear to me that the protests learned a lot from the Black Church. However, I’m not sure that the Black Church has learned much from the protests. One reason I say this is that the protests were led primarily by Black women, by Black queer women in many cases. This does not fit the male-dominated image of religious social justice leaders that we have from the Civil Rights era. Across our churches, these women protest leaders would not have the ability to shout or preach from pulpits because they are women, because they are queer. This exposes the beauty and the pain of what we understand the Black Church to be.

The pandemic has limited “foot traffic” at the Divinity School and the exhibit. So it’s been tremendously advantageous that the exhibit also exists online and that the web version includes extra features, including recordings of interviews you’ve done with church members. What are some of the recurring themes listeners hear when they engage these interviews?

Most important, each interview conveys an undying love for the person’s institution. Some of the people I interviewed are senior citizens now and they’ve been part of the same church since they were children. Or they’ve pastored their church for decades, or they joined the church because they married into the church many years ago. The church is an intimate place for them, and they care about it just as they would care about their home and their family. The people there are their church family.

You and your team could have mounted this exhibit at any number of places. Why did you choose to have it at YDS, and what do you hope the YDS community has learned from it these past couple of months?

I have found that classes can’t quite capture the full range of experience that forms Black religious life. We have ecumenical worship in our chapel services, but often the only avenue of the Black Church that is included is our music, so much is left unexplored. The exhibition is my attempt to show a fuller range of Black Church experiences and expressions.

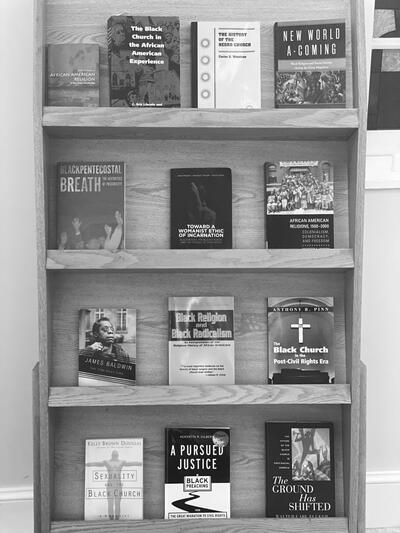

I was also intent on engaging the scholarship around Black churches. One of the elements of the exhibit that I’m most excited about is the small bookshelf in the corner. It seeks to provide a bibliography of scholarship about the issues explored in the exhibit, including YDS Professor Eboni Marshall Turman’s work Toward a Womanist Ethic of Incarnation, where she discusses the experiences of Black women in the church.

I was also intent on engaging the scholarship around Black churches. One of the elements of the exhibit that I’m most excited about is the small bookshelf in the corner. It seeks to provide a bibliography of scholarship about the issues explored in the exhibit, including YDS Professor Eboni Marshall Turman’s work Toward a Womanist Ethic of Incarnation, where she discusses the experiences of Black women in the church.

I also wanted to show the YDS community the importance of materiality in the Black Church tradition—for example the special clothing that ushers wear and the preaching robe of the Rev. Shevalle Kimber (‘21 M.Div.), a current student and a New Haven pastor. The histories, the music, the books, the clothing all work together to make the Black Church what it is.

What you are studying at YDS and what you want to do after YDS?

Currently I’m working on a thesis centering African American homegoings, particularly with respect to racialized terror in America. The project is thinking through the ways that African American Christians have fashioned the funeral space to reinscribe dignity to those who have died through violent acts—racialized violent acts—and how this kind of curating requires a reckoning with racism in this country.

I’m currently applying to Ph.D. programs in American religious history and hoping to pursue an academic career. I want to continue to engage what Black death looks like, particularly from a religious standpoint. I also plan to continue to record and tell the story of Black sacred spaces, including Black Christian churches but also expanding the work to other forms of Black religious practice.

Whatever shape my career takes, my goal is to curate African American religious history and help preserve Black institutions generally—and to support the development and training of future Black curators who can take up the mantle that I’ve taken up and continue doing the crucial work of recording and understanding the complexities, beauty, and strength of these religious institutions.