By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

Born in Philadelphia in 1943, Marylouise Oates ‘73 M.Div. has spent her life breaking barriers and helping those in need. These values were planted in her childhood.

“My dad was a union organizer,” she said. “He never finished high school but was brilliant. And my mother’s father was a politician. They had a great influence on me.”

Oates—who everyone calls Oatsie—is grateful for the support of her parents. “My parents told my sister and me that we could do anything,” she said. “That was very rare for girls to hear in those days.”

In 1961, Oates enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania and pursued her love of writing.

“I was only there for five semesters and majored in working on the student newspaper,” she said with a laugh.

Oates left school early to work full time as a reporter. As the youngest national reporter for United Press International (UPI), she covered the 1964 Democratic Convention and the Philadelphia race riots.

Oates left school early to work full time as a reporter. As the youngest national reporter for United Press International (UPI), she covered the 1964 Democratic Convention and the Philadelphia race riots.

“The riots stemmed from police brutality,” she said. “They were some of the first riots of the civil rights era and left a deep impression on me.”

After working for UPI in New Jersey and then New York, the renowned journalist Seymour Hersh encouraged Oates to join the Eugene McCarthy presidential campaign as Deputy National Press Secretary.

“Working for the McCarthy campaign with Seymour was a great experience,” she said. “Afterward I covered the Poor People’s Campaign, and then I went to the University of California, Berkeley, to interview the student body president, Charlie Palmer. It was a great interview. Charlie and I became a couple, and I stayed in Berkeley. Activism was a big part of our lives.”

Life at Yale

When Palmer graduated from Berkeley, he was elected President of the National Student Association, so he and Oates moved to Washington. While Palmer helped organized students around the country, Oates ran the press operation for the Vietnam Moratorium and the National Welfare Rights Organization. A year later, the couple moved to New Haven.

“Charlie started Yale Law School in September 1970—the same month we got married,” she said.

“Charlie started Yale Law School in September 1970—the same month we got married,” she said.

While Palmer studied law, Oates was encouraged to study at Yale Divinity School.

“My friend said it was the greatest liberal arts education in America, so I applied,” she said.

Never having finished her bachelor’s degree, Oates was initially turned down by YDS. Oates, however, had an ally on the inside.

“The student on the acceptance committee told me I should write an appeal and talk about all the activism I had done, especially around peace and poor people’s issues, so I did just that,” she said. “The committee changed their minds, and I started in January 1971.”

Oates still remembers her first day of classes.

“I didn’t think I could handle it because the other students used so many words I didn’t know,” she said. “But I just started to look the words up and soon realized that my life experiences were much greater than any fancy language.”

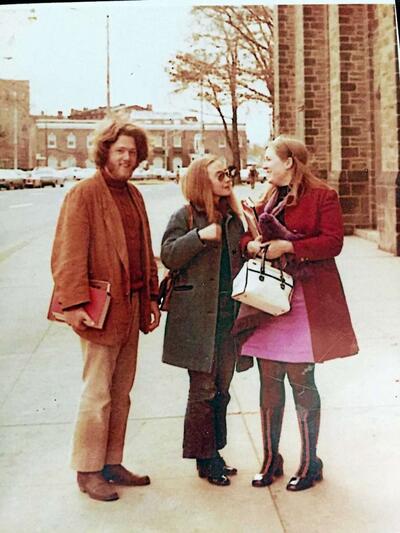

Oates continued her activism while at YDS, including joining a consciousness-raising group, putting together a women’s conference, and helping Yale’s female staffers to organize and fight for their jobs. She also befriended two law students at the time—Bill Clinton and his then-girlfriend, Hillary Rodham. Oates shares how the future President “came to her rescue.”

“My father was in Philadelphia and very ill,” she said. “Bill would lend me his car to go see him. My dad survived, as did my friendship with Bill. Even back then, you couldn’t help but like him. He was so naturally charismatic.”

“My father was in Philadelphia and very ill,” she said. “Bill would lend me his car to go see him. My dad survived, as did my friendship with Bill. Even back then, you couldn’t help but like him. He was so naturally charismatic.”

In the classroom, Oates remembers two professors who had a profound impact on her.

“I took Sydney Ahlstrom’s big lecture course on the religious history of the American people,” she said. “He was brilliant. I learned so much.”

One day, Oates approached Ahlstrom and said she’d like to do an independent study on the McCarthy era.

“He said he didn’t know very much about it, and then suggested we research it together,” she said. “So, I had Sydney Ahlstrom alone for two hours every Friday. It was such a gift.”

Another influential professor for Oates was Harry Baker Adams, an assistant dean who taught expository preaching.

“I didn’t want to preach and didn’t know what to do,” she said. “Adams told me to go home and read the story about the loaves and fishes ten times. I did just that and came to a realization: The real miracle in that story was that the crowd opened their bags and shared. How beautiful is that?”

After graduating in 1973, Oates and Palmer moved to California. Palmer started a job at a law firm while Oates worked as a writer for Lutheran Social Services.

“I became pregnant shortly after moving to California,” she said. “I had toxemia and was in bed for many weeks, but I finally gave birth to my son Michael in September 1974.”

Shortly after giving birth, Oates was approached by the California Rural Legal Assistance and began working with them on a food stamp program.

“We started the Hunger Hotline, and it was on the TV news,” she said. “The phones just blew up. There were so many people in need.”

A writer’s life

In tandem with motherhood and activism, Oates picked up part-time work reviewing fashion books and was hired as a copy editor at the Los Angeles Times. Not one to wait for opportunities, Oates decided to pitch a story on religion. Her first piece was about the Jews in Los Angeles who had given up attending synagogue on Friday nights and instead had havurahs—small groups who gathered regularly for prayer and study—in their homes.

“I turned in the piece to one of the editors and was told that I wouldn’t hear for a few weeks,” she said. “It was on the front page the next day. The story would never have happened if I hadn’t attended YDS. It helped make my career.”

Oates was soon hired to work for the society pages and would eventually have her own column. Although the column had previously been written in a more conservative style, she made it her own by highlighting issues of justice. There were light-hearted assignments as well.

“I followed Bob Hope around for three weeks when he was turning eighty,” she said.

“His PR guy told me not to ask him about women, but I did anyway. Hope just laughed and said, ‘I’ve always loved the ladies.’ His politics weren’t my politics, but he was charming and great.”

Oates’s column soon grew to three times a week, and she made sure to use the space wisely.

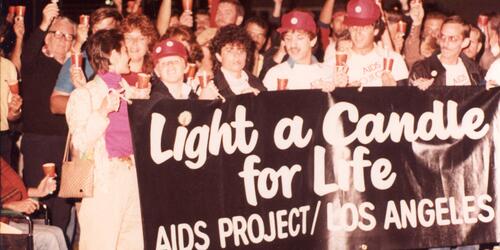

“I started writing about AIDS in 1985,” she said. “Betty Ford got involved in the issue, and she got Elizabeth Taylor involved. AIDS Project Los Angeles had a big fundraiser put together by prominent AIDS activist Peter Scott. It was a huge success, made money for direct services, and helped raise awareness.”

In her column and pieces for the View section, Oates emphasized inclusivity. She wrote about Black sororities and did a “huge piece” on quinceañeras.

“I got to cover everything,” she said. “I wrote a piece on Betty Ford when she opened her center. She was a remarkable woman. I also covered movie, music, and TV stars, the glitterati, along with political money.”

Another issue she focused on was the cost of the centerpieces and decorations at charity dinners.

“My campaign worked,” Oates said. “People started to feel ashamed about the money spent on flowers and favors and scaled back.”

Kathleen Hendrix was also a writer at the Los Angeles Times with Oates. They remain close to this day.

“We worked together and realized we had a lot in common,” Hendrix said. “Marylouise has an extraordinary understanding of how power is used, which is society writing at its best.”

Hendrix believes that Oates “widened the column’s scope.”

“She wrote about nontraditional issues like better housing on Skid Row,” she said. “The column took a larger-than-life significance. It became very important.”

After she left the Times, Oates wrote several books and volunteered for causes such as LGBTQ rights and served on the National Board of the Human Rights Campaign Fund. She also spearheaded a project to help the women of Northern Ireland after the Good Friday Accords put an end to the Troubles. She created the Friends of the Communities of Northern Ireland and worked with First Lady Hillary Clinton on the global initiative to empower women.

After she left the Times, Oates wrote several books and volunteered for causes such as LGBTQ rights and served on the National Board of the Human Rights Campaign Fund. She also spearheaded a project to help the women of Northern Ireland after the Good Friday Accords put an end to the Troubles. She created the Friends of the Communities of Northern Ireland and worked with First Lady Hillary Clinton on the global initiative to empower women.

“Hillary is magnificent when she talks to women overseas,” said Oates. “She does not talk down to them, but right to them. She is very empowering. I first visited Ireland with her in 1998 and was inspired to help women from Northern Ireland to speak up for themselves.”

On the home front, Oates and Palmer amicably separated in the early eighties.

“We had a wonderful divorce,” Oates said.

Oates’s son, Michael, is currently a television writer in Los Angeles. He shares what his mother taught him about community.

“When my mom was working at the Los Angeles Times, we’d always have people at the house,” he said. “I grew up with a seat at the table. There were activists, writers, photographers, politicos, and journalists. One of the seminal memories of my childhood is seeing that energy and activity at that table and seeing friendship at work. I thought, ‘This is good. I want this in my life.’”

“When my mom was working at the Los Angeles Times, we’d always have people at the house,” he said. “I grew up with a seat at the table. There were activists, writers, photographers, politicos, and journalists. One of the seminal memories of my childhood is seeing that energy and activity at that table and seeing friendship at work. I thought, ‘This is good. I want this in my life.’”

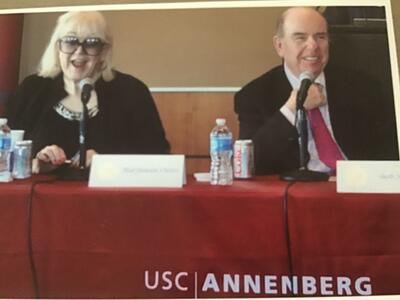

For the past 33 years, Oates has been married to Robert “Bob” Shrum, the renowned political strategist and speechwriter who worked on Senator Edward Kennedy’s presidential campaign as well those of John Kerry and Al Gore. Now the Director of the Center for the Political Future and the Carmen H. and Louis Warschaw Chair in Practical Politics at the University of Southern California, Shrum’s face lights up when asked about his wife.

“She is the spirit of life,” he said. “She’s incredibly smart and a gifted writer. Her commitment to generosity and service runs through everything she does.”

Shrum also offers praise for his wife’s hospitality.

“She happens to be an amazing chef,” he said. “When we were living in Washington, I’d sometimes call her last minute to say people were coming to dinner, and she never complained. She enjoys cooking and opening our home to others. Hospitality is part of her ministry.”

While the quarantine of the past year challenged many couples, Shrum says their relationship thrived.

“My wife is my whole life,” he said. “The pandemic has been a horrible time, but it was a wonderful time in one way because we spent all our time together. The quarantine was a test of whether you not only love each other but like each other. We made it through stronger than before.”

Touching the future

Oates has just finished a memoir about her life in the Sixties, appropriately titled “The Only Girl in the Room.”

“It’s an apt title,” she said. “With my reporting background, I wound up being just that.”

Although she turns 78 in December, Oates shows no signs of slowing down. She spends much of her time working with the Downtown Women’s Center (DWC) in Los Angeles, which offers housing, healthcare, and employment services for 5,000 women a year on Skid Row. Women’s Center CEO Amy Turk is very grateful for Oates’s involvement.

Although she turns 78 in December, Oates shows no signs of slowing down. She spends much of her time working with the Downtown Women’s Center (DWC) in Los Angeles, which offers housing, healthcare, and employment services for 5,000 women a year on Skid Row. Women’s Center CEO Amy Turk is very grateful for Oates’s involvement.

“A few years ago, Marylouise helped pass an important measure in Los Angeles,” said Turk. “The voters agreed to tax themselves a quarter-cent sales tax. The money goes directly to service providers that work with the homeless population. It brings in 400 million dollars a year for the whole system.”

Oates also helped the center establish its big annual fundraising dinner.

“We honored Marylouise at our signature event in 2016, and it has been our largest fundraising event to date,” said Turk. “Everyone came out for Oatsie.”

With the money Oates has helped raise, the DWC is opening four new sustainable houses for homeless women. To honor her contribution, one of the buildings is named “Oatsie’s Place.”

“Some 50,000 people live on the streets of Los Angeles County, and a quarter of them are women,” said Oates. “The DWC staff, its thousands of volunteers, and all its contributors are doing the work of peace and justice every day. And isn’t that what ministry is all about?”

Looking back on the scope of her life’s work, Oates emphasizes the importance of her time at YDS.

“I think Yale helped me to ask different questions,” she said. “It impacted my thinking.”

Shrum agrees.

“When my wife talks about Yale, she is filled with brilliant, shining memories,” he said.

To honor her YDS experience, Oates created a scholarship for mid-career women who want to go into ministry. The Marylouise Oates Endowed Divinity Scholarship Fund was formally established in 2016.

“My time at Yale Divinity School opened my mind and my heart,” she said. “It gave me a broader perspective and made me more sympathetic. No matter what I’m doing, the lessons I learned float in the back of my mind. It is such a gift to share this experience with others.”

—-

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.