By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

As a child growing up in Panama, Marta Illueca ’18 M.Div. became accustomed to life in the public eye.

“My father was dedicated to social justice,” she said, “and very active in politics.”

“Starting in 1984, my father was president for a year and a half,” Illueca said. “Suddenly, each family member had a bodyguard and code name. But my father was very humble and made sure we all stayed grounded.”

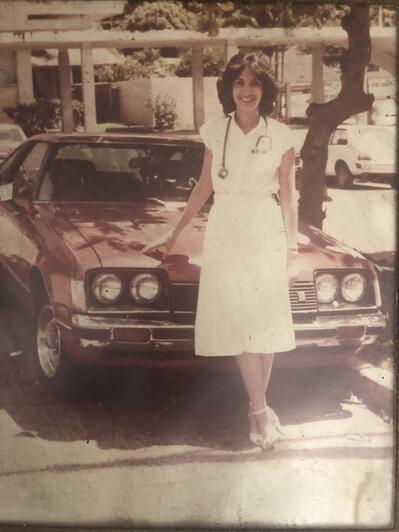

While her father worked on housing for the homeless and other progressive reforms, Illueca’s mother was also busy serving her country. Passionate about health, she was a nurse who founded Panama’s first nursing college.

“My mother really elevated Panama’s nursing education,” said Illueca. “It was her calling. Both my parents were great role models for me and my siblings.”

Tragedy hits home

While her mother sparked Illueca’s initial interest in medicine, it was a family tragedy that would ultimately lead to a lifelong healing quest for herself and others.

“When I was 12 years old, my sister—who was nine years older than me—died suddenly from an undiagnosed heart condition,” Illueca said. “It was extremely traumatic, and it pushed me towards medicine. I wanted to understand why her condition went undiagnosed.”

The death of her sister affected other aspects of Illueca’s life as well.

“Internally, it started my whole spiritual journey,” she said. “I began having intense mystical experiences.”

Illueca describes moments of feeling as if she were outside her body, seeing lights, and having detailed dreams.

“I realized we are more than the physical body,” she said. “We have a spirit and different layers to our constitution.”

Raised in a traditional Roman Catholic family, Illueca started researching other beliefs, including Eastern spirituality, theosophy, and Jewish mysticism.

“I found beauty and wisdom in everything I studied,” she said. “The mystical experiences stopped when I was around eighteen, but my outlook on life changed forever.”

A life in medicine

Illueca would go on to college and medical school, graduating at the top of her class.

“I was valedictorian and accepted to Cornell University Medical College for a pediatrics and gastroenterology residency,” she said.

After her successful training, Illueca continued to practice medicine at Cornell for the next two decades. In 2003, she sought to learn how to develop new medical treatments and moved to Delaware to work for AstraZeneca in the pharmaceutical industry.

After her successful training, Illueca continued to practice medicine at Cornell for the next two decades. In 2003, she sought to learn how to develop new medical treatments and moved to Delaware to work for AstraZeneca in the pharmaceutical industry.

“I wanted to be part of therapy research and development, not just limited to prescribing existing treatments,” she said.

Illueca led the company’s Nexium pediatric program, helping children who suffered from acid reflux.

“We developed an FDA-approved pediatric treatment that can be used as early as one month of age,” she said.

While immersed in the world of medicine, Illueca never abandoned her spiritual journey. One day, after catching a Broadway show in New York, she stepped outside of the theater and was immediately captivated by a beautiful church.

“Something about that church just drew me in,” she said. “It was during a high church mass and there was lots of incense. As a Roman Catholic, I liked ceremony and ritual. I had no idea it was an Episcopal church.”

Illueca felt connected to this “very sacred space” and went on to find a similar Episcopal church near her home in Delaware.

“I found this beautiful Episcopal church where the rector was a woman, so she became my role model,” said Illueca. “I needed to be in a place where I could see the possibilities for a woman. Before that, I never thought I could become a priest. That church became my temple.”

Back to school

While growing more active in her church, Illueca felt called to delve deeply into the world of spirit. She decided to attend Berkeley Divinity School, the Episcopal Seminary at YDS. As Illueca prepared to enter Berkeley, she began her last project at AstraZeneca.

“My final project dealt with chronic pain,” she said. “It was then I saw a presentation by Dr. Daniel Carr, the director and founder of Tufts University’s Pain Research, Education & Policy Master’s program. I was so impressed with his depth of knowledge.”

Carr’s program at Tufts looked more deeply at pain through a variety of disciplines, including ethical, sociocultural, and spiritual dimensions. Illueca says that watching his presentation and speaking with him afterward felt “like an epiphany.”

“At that moment I realized that my true calling is to bring spirituality and medicine together,” she said. “Carr’s comprehensive pain program appealed to my holistic outlook on medicine, and I wanted to learn more. I began studying at Berkeley and his program at the same time. It just felt right.”

Carr refers to Illueca as “a real standout” and believes her work exemplifies the shift in emphasizing pain “as an experiential thing and not just what happens when you injure tissue.”

“Marta is drawing together different fields of knowledge and helping to further our understanding,” he said. “She is addressing the fundamental question of defining pain, including spiritual pain.”

At YDS, one formative class for Illueca was Theology and Medicine with Dr. Benjamin Doolittle ‘91 B.S., ‘94 M.Div., ’97 M.D. The course explores contemporary medicine from a theological perspective and covers such topics as suffering and healing that resonate in both fields.

Among a number of positions, Doolittle is the Program Director of the Combined Internal Medicine-Pediatrics Residency Program and the Director of the Yale Program for Medicine, Spirituality & Religion. His research interests explore “the intersection of medicine and spirituality, wellness and burnout.” He is also the pastor of Pilgrim Congregational Church in New Haven.

“I pastored as a medical student and as a resident, and I’m still doing it,” Doolittle explained. “I love it.”

Studying with Doolittle was informative for Illueca, and she decided to apply some ideas from class to her master’s thesis at Tufts.

“I wanted to do a formal, systematic review on the clinical research about pain and prayer,” she said.

Illueca asked Doolittle if he’d be her thesis director, and he was up for the challenge.

“It was a joyful collaboration,” Doolittle said. “In modern society, we often separate things like pain and prayer. We talk about the body, spirit, and mind, but it seems to me that they’re all part of the same thing. We can’t really separate them because the deepest questions of meaning and life and love are always spiritual questions. What it means to be healthy in body can never be separated from a person’s emotional wellbeing or spiritual health.”

“It was a joyful collaboration,” Doolittle said. “In modern society, we often separate things like pain and prayer. We talk about the body, spirit, and mind, but it seems to me that they’re all part of the same thing. We can’t really separate them because the deepest questions of meaning and life and love are always spiritual questions. What it means to be healthy in body can never be separated from a person’s emotional wellbeing or spiritual health.”

Illueca and Doolittle adhered to the stringent criteria of analyzing over 400 previous study reports, with only nine fitting their standards. After their analysis, they found that personal prayer—as opposed to group or distant prayer—is more helpful for healing pain. The research also shows greater positive results when a person uses “active prayer,” a term coined by Samantha Meints, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Active prayer is like asking God to empower you and provide you with the tools needed to overcome the pain,” Illueca said. “It’s a more beneficial coping strategy than just passively asking God to take the pain away.”

During Illueca’s thesis preparation, she contacted Meints and proposed that they develop an instrument or scale dedicated to characterizing prayer used by people with chronic pain. Meints enthusiastically agreed.

A new vocation and a new study

Illueca is now an ordained Episcopal priest at Brandywine Collaborative Ministries in Delaware and spends much of her time giving sermons and providing pastoral care. Although her life looks different now, medicine still plays an important role. She is a COVID advisor for the country of Panama and is conducting an in-depth study on pain and prayer. The ongoing study began last October and is partially funded by the 2020 United Thank Offering grant, a ministry of the Episcopal Church.

“Meints and I are creating what will be the first-ever scientifically validated prayer scale and will ultimately use it to design a bedside prayer tool,” Illueca said.

While not a spiritual person, Meints believes it’s important to research the intersection between science and religion—an area she calls “understudied and often overlooked.”

“Much of our world is religious or spiritual, yet this is often seen in opposition to science and Western medicine,” she said. “We are studying the overlap between these areas to better understand how we can harness the power of prayer in helping folks manage chronic pain.”

The study is unique for Meints, as well as challenging.

“I lean on science and hard data to guide me,” she said. “Marta, however, has been able to blend medicine and religion through the course of her career. I find it inspiring that she is a strong proponent of how these worlds can mesh together quite seamlessly.”

Indeed, Illueca hopes that this study will help strengthen the connection between medicine and religion.

“We are creating a new research model where church and academia collaborate,” she said. “For too long, spirit and medicine have been unnecessarily separated. I want to bring these worlds together in ways that are both scientifically validated and holistically healing.”

Illueca talks about her work with great passion and energy, and she credits her faith for her vitality.

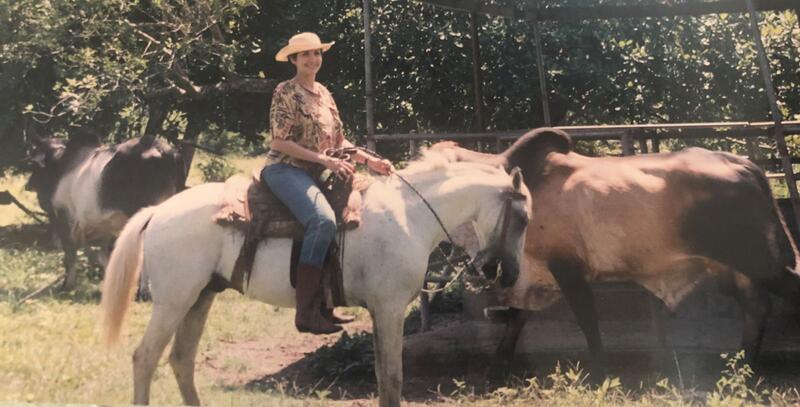

“I am inspired by life, and at 61, I’m just getting started,” she said. “The first thing I do every morning is to thank God for a new day. I try to see God in everyone I see and in everything I do. I believe I am being guided, and I am deeply grateful for everything in my life—past, present, and future. I feel very blessed.”

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.