By Ann-Catherine Wilkening ’19 M.A.R.

On a Tuesday last March, I was working my shift as a student worker in the Divinity School’s bookstore. As I placed price tags on a new shipment of books, a woman walked into the store and inquired where she could find pictures of previous graduating classes. I asked my visitor which class year she was looking for, since Yale Divinity School class pictures are hung up in chronological order throughout the building. “Nineteen twenty-eight,” she replied, “that is when my aunt went here.” I offered to accompany her to find her aunt’s picture.

On our way, the woman, introducing herself as Dr. Catherine Kling, disclosed more information about her aunt, Louise Triplett. In the late 1920s, Louise attended Yale in a Master of Education program. However, as Louise’s obituary indicates, she did not receive her degree from YDS since the school did not allow women to seek degrees until 1932. Louise graduated with an Education degree from Yale’s Graduate School in 1928 instead. Yet, Catherine told me her aunt completed most of her coursework at YDS and considered it a formality that her degree was conferred by the Graduate School rather than the Divinity School.

On our way, the woman, introducing herself as Dr. Catherine Kling, disclosed more information about her aunt, Louise Triplett. In the late 1920s, Louise attended Yale in a Master of Education program. However, as Louise’s obituary indicates, she did not receive her degree from YDS since the school did not allow women to seek degrees until 1932. Louise graduated with an Education degree from Yale’s Graduate School in 1928 instead. Yet, Catherine told me her aunt completed most of her coursework at YDS and considered it a formality that her degree was conferred by the Graduate School rather than the Divinity School.

Unsurprisingly, Catherine and I could not find Louise’s picture in the YDS graduating class photo of 1928. Yet, after meeting Catherine, I was intrigued by the story of a woman seeking a religious education at Yale Divinity School before the school’s co-educational reforms took place, and I was determined to find out more about Louise and her position within YDS. Little did I know that I was digging myself an archival rabbit hole that would keep me busy for weeks.

When I initially became of aware Louise’s story, I thought she might have been a singular case. But as I would learn, the history of women attending Yale Divinity School reaches back 20 years before Louise Triplett. As it turns out, Louise was one of many women who attended YDS before co-educational reforms took effect, as either non-degree-seeking students or Yale students enrolled in other schools.

Not stopped by official policy

Before then, Yale promulgated the following policy regarding women students: “Properly qualified women are admitted as candidates for all degrees except those offered by the two Undergraduate Schools, the Divinity School, the School of Forestry, and the higher degrees in Engineering.”[1] Yet this did not stop women from taking classes at YDS. From 1907 on, women appear in the School’s records in lists of students from other departments. The first two, appearing in the Eighth General Catalogue of the Yale Divinity School, were Lottie Genevieve Bishop and Ethel Zivley Rather.[2]

Although women appear only sporadically in the records of the first two decades of the 20th century, they attended YDS continuously beginning in 1920. Their numbers are comparable to the number of women who enrolled in YDS as degree-seeking students from the mid-1930s to the 1950s. I would even suggest that the school’s move to the remote location of the newly constructed Sterling Divinity Quadrangle in 1932 inhibited women from affiliating with the school. In addition to developing statistics and recovering the names of these women, I have tracked down traces of their biographies, though many remain uncovered.

Louise Triplett is listed as an affiliated Education Department student in the Divinity School’s bulletins in 1927-28 and 1928-29, under the heading “Students from other Schools of the University.”[3] The two bulletins list 15 and 16 other women, respectively—mostly from Education, but also from the departments of Religion, History, English, and Economics, and from the Sociology and Government graduate degree programs. In both years, women made up just over 25% of students from other schools of the University listed in the YDS records.

Percentagewise, the statistical high-water mark for women in this era was in 1920-21, when women constituted 63% of students from other parts of the university listed as taking classes at YDS. Between 1921 and 1932, the absolute numbers of women in this group fluctuated while gradually trending upward. These numbers are quite astonishing given the fact that the Divinity School would later limit the women admitted to its degree programs to a maximum of 10 per year until the 1950s.

The vast majority of women who studied at YDS in the 1920s and early 1930s were Master of Arts degree candidates from the Education Department, often with a concentration in Religious Education. At that time, YDS was running a department of religious education, established in 1917,[4] meaning non-Divinity students interested in religious education would have taken classes at YDS.

Louise Triplett, born in 1904, came from a family of ministers. After she graduated from Yale with a Master’s in Education, she began a long career in service to congregational churches. She worked as a director of religious education at a congregational church in Manchester, N.H., and later at Plymouth Congregational Church in Seattle. Later in her career, she was director of religious education and young people’s work in the Congregational church conferences of Wisconsin and Ohio. In the final years of her professional life, she followed a call to serve at a church in Hawaii. There, she became a supporter of the civil rights movement, especially during the Montgomery march, as her niece Catherine proudly told me. She passed away on December 21, 1983.[5]

Beyond Louise Triplett’s story, I found other hints that many women graduate students primarily attended YDS classes: In 1982, the Yale Alumni Magazine published an article on another non-Divinity graduate who appears in YDS records between 1930 and 1933: Lavinia Scott. The magazine later interviewed Lavinia about her time at Yale and her subsequent career. During her interview, Lavinia stated that “she did at least half her work at the Divinity School.” Immediately after her graduation in 1932, Lavinia left America to move to South Africa as a missionary and teacher, a calling that she had felt since her childhood and had brought her to Yale in the first place. In South Africa, Lavinia worked as a teacher and, eventually, the principal of Inanda Seminary, a secondary school for Zulu girls. During the rise of apartheid, Lavinia fought to keep her school from becoming government-controlled and also served as a substitute teacher for the education of black ministers at a theological seminary before returning to and retiring in the States in 1974.[6]

Not all women students from other departments at Yale went on to serve as religious educators for churches and secondary education. Some of them received their doctorates and pursued careers in academia, such as Dr. Shina Inoue Kan.[7] Shina appears as a Philosophy and Psychology graduate student in the 1925-26 and 1926-27 YDS bulletins. She graduated from Yale in 1927 with a dissertation titled “Leibniz and Fichte on the Nature of Will.” After leaving Yale, she pursued further studies at Columbia and Union Theological Seminary. Throughout her career, Shina was heavily invested in Japanese peace work and efforts to continue the education and emancipation of Japanese women.[8]

Between 1920 and 1927 the YDS Bulletin also lists students who were not enrolled at Yale but took classes at the school as non-degree seeking students. Women in this group rose from 27% (seven out of 26) in the 1920-21 academic year to 47% (eight out of 17) in 1926-27. After that, the bulletin no longer lists non-degree students, and it is unclear if the school still allowed non-Yalies in the classroom. Nonetheless, some of these students stayed at YDS for more than one year, demonstrating another way women found to obtain a Yale Divinity education without seeking a degree from the school.

One of these women was the Rev. Elsie Stowe, a pioneer in women’s ministry and ordination who appears in the records as a student “pursuing resident study not leading to a degree” for three consecutive academic years from 1920 until 1923. Elsie was the first woman ordained in the New York East Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. She first came to New Haven in 1916, where she enrolled for two years at the Blakeslee Deaconess Training School. She served as pastor and deaconess in various Connecticut and New York churches from 1917 onwards. In 1920, the same year she came to Yale, she was consecrated as a Methodist Episcopal Deaconess and granted a local preacher’s license at the First Quarterly Conference of the Newtown Church. With this license she had the opportunity to perform wedding, baptismal, and burial ceremonies. Elsie indeed officiated the wedding of her own brother in September 1924.[9]

New location up the hill

Another factor contributed to so many Yale women affiliating with YDS before the admissions reform: the school’s location. Until 1932, the Divinity School was located in the heart of Yale’s downtown campus at the present-day site of Grace Hopper College. This location made it easier for students from other departments to take classes at YDS and placed the school in closer proximity to broader campus life.

In 1932, however, big changes came to YDS. The school moved to Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, approximately one mile up Prospect Hill. The relocation contributed to women’s struggles to attend the school in subsequent years. Around the same time, YDS decided to admit women to the Bachelor of Divinity program (the equivalent of today’s M.Div.). In 1933, the percentage of students who were women affiliates from other parts of Yale dropped to its lowest point since 1919, at 6%. Women affiliates rose to 16% over the next two years—still well below the figures of the late twenties.

Esther Temperly Barker, who was a degree-seeking student at YDS in 1936, remembers the difficulties of being a woman at YDS at the time. Among other obstacles, women had no place to live on Sterling Divinity Quadrangle. In February, after a snowstorm, Barker was “one of the very few people who got up there that morning.” The men who lived in the Quad residences, however, enjoyed the snow, donning swimsuits and hamming for photos.[10]

Bernice Buehler ’35 B.D., one of the first women to graduate from YDS, remembers that the school “did not make any arrangements for women to be in the dorms at that time.” Although they appreciated the resources available to them as full-fledged divinity students, “the women felt a little left out that we could not [live] on campus, she said.”[11] In the end, the move to Sterling Quadrangle, which secluded YDS from the rest of campus downtown and made it more self-contained with its own refectory and (male) dormitories, gave the school more of a boy’s club feel than it had in the 1920s when it was in the vicinity of other graduate programs and more easily accessible for Yale women.

Recovering the lost stories

The stories of the first women attending YDS have often been ignored outside of commemoration anecdotes. Further, the women who attended YDS before 1932 are not part of the narrative that the school tells about its institution today. The YDS website and the school history displayed on a wall near the Admissions Office mention nothing about the earliest women at YDS. According to the school’s website, the “first women of YDS” were Buehler and Thelma Diener Allen ‘35 B.D., “the first two women to complete the full course of study and graduate from YDS in its current location.”[12]

Whether women received degrees is an important question because degrees are credentials that provide proof of one’s education and help one to find a job within a professional field. Yet, there were many women of YDS who came before Bernice and Thelma, though marginalized by the school’s admission policy. Even without seeking YDS degrees, their presence would have shaped the school, including the classroom, as much as they were shaped by it. Some of them considered the Divinity School their primary place of educational belonging while they studied at Yale. Later in their lives, many of these women influenced the worlds of religion in important ways. Their education at Yale took them along diverse career paths in the field of religion and ministry, as they became professors, preachers, missionaries, and religious teachers.

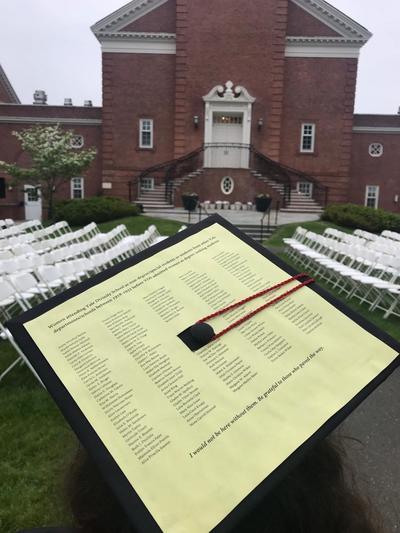

My research has only scratched the surface and has highlighted just a few early YDS women. Much work remains to be done, especially with respect to the history of early women of color, such as the aforementioned Dr. Shina Inoue Kan. In light of the 150th anniversary of women at Yale being celebrated this year, it is imperative to think hard about and, indeed, revise who we remember as a school and who we leave out. The recovery of the names and stories of the women who slipped through our institutional memory can challenge our established narratives.

In recent years, YDS has, thankfully, made efforts to remember and celebrate its first black student, the Reverend Dr. James W.C. Pennington, an escapee from slavery who attended Divinity School classes in the 1830s and, like the women I researched last spring, never received a degree from the school. Many of the women who attended YDS before 1932 were pioneers in a larger historical trajectory of women’s emancipation in ministry, theology, and religious studies. Women such as Louise Triplett likely influenced and paved the way to the later decision to grant women full and equal access to a Divinity School education. It is my hope that YDS eventually finds a way to memorialize these women more permanently and acknowledge their stories as part of the school’s history.

Ann-Catherine Wilkening ’19 M.A.R. is entering a Ph.D. program at Harvard in the Religions of the Americas subfield. She is particularly interested in how non-English archival sources might be better incorporated into historical research in order to tell the stories of often disregarded and marginalized groups in American history, as well as how these stories might shape our historical understanding of religion, race, gender, and sexuality in early North America. She also enjoys taking her family’s pony, Stella, on long rides through the southern German countryside.

Ann-Catherine Wilkening ’19 M.A.R. is entering a Ph.D. program at Harvard in the Religions of the Americas subfield. She is particularly interested in how non-English archival sources might be better incorporated into historical research in order to tell the stories of often disregarded and marginalized groups in American history, as well as how these stories might shape our historical understanding of religion, race, gender, and sexuality in early North America. She also enjoys taking her family’s pony, Stella, on long rides through the southern German countryside.

Sources Cited

“Bulletin 1856-1959,” Yale University Divinity School memorabilia collection RG 53 Series IV Box IV-2. Yale Divinity Special Collections.

Doctors of Philosophy of Yale University: With the Titles of Their Dissertations, 1861-1927. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1927.

“Eight Decades of Women at Yale Divinity School.” Yale Divinity School, n.d. http://divinity-adhoc.library.yale.edu/Exhibits/Eight%20Decades%20of%20Women%20at%20YDS.pdf.

“First Women of YDS.” Yale Divinity School. Accessed April 14, 2019. https://divinity.yale.edu/gallery/first-women-yds.

“New Department of Religious Education at School of Religion.” Yale Daily News. March 1, 1917, Vol. XXXX No. 119 edition.

“Shina Inoue Kan 1949.” Newspapers.com. Accessed May 5, 2019. http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397346/shina_inoue_kan_1949/.

“Shina Inoue Kan 1955.” Newspapers.com. Accessed May 5, 2019. http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397477/shina_inoue_kan_1955/.

“Shina Inouye 1922.” Newspapers.com. Accessed May 5, 2019. http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397268/shina_inouye_1922/.

“Shina Kan 1950.” Newspapers.com. Accessed May 5, 2019. http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397651/shina_kan_1950/.

Stearns, Catherine. “‘The Power of Love’: A Missionary Finds Her Niche in South Africa’s Stormy History.” Yale Alumni Magazine, November 1982.

United Methodist Church. “Rev. Elsie F. Stowe Spring 2011.” Accessed May 3, 2019. https://www.nyac.com/revelsiefstowespring2011.

“Yale Divinity School’s Women’s History Project,” n.d. Yale University Divinity School memorabilia collection RG 53 Series VI Box II. Yale Divinity Special Collections.

Yale University, ed. Eighth General Catalogue of the Yale Divinity School, Centennial Issue, 1822-1922. Bulletin of Yale University. New Haven: Yale University, 1922.

[1] See e.g. “Bulletin” (1931/32), Yale University Divinity School memorabilia collection RG 53 Series IV Box IV-2, Yale Divinity Special Collections.

[2] See Yale University, ed., Eighth General Catalogue of the Yale Divinity School, Centennial Issue, 1822-1922, Bulletin of Yale University (New Haven: Yale University, 1922), 422, 427. Interestingly, Lottie Bishop was also one of the Yale alumni administrators in charge of putting together this catalogue. Other women attending YDS before 1918/19 appear on ibid., 334, 440, 443, 446, 457,460, 470, 479, 509.

[3] All bulletins I used as primary sources for m study can be found in “Bulletin 1856-1959”, Yale University Divinity School memorabilia collection RG 53 Series IV Box IV-2, Yale Divinity Special Collections.

[4] See “New Department of Religious Education at School of Religion,” Yale Daily News, March 1, 1917, Vol. XXXX No. 119.

[5] See Appendix II. Illustration 1 and Louise Triplett, Presenting Missions: Methods for Youth Groups (New York: Friendship Press, 1948).

[6] Catherine Stearns, “‘The Power of Love’: A Missionary Finds Her Nice in South Africa’s Stormy History,” Yale Alumni Magazine, November 1982.

[7] She also appears in records as Shina Inouye.

[8] See Doctors of Philosophy of Yale University: With the Titles of Their Dissertations, 1861-1927 (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1927), 150; “Shina Inoue Kan 1949,” Newspapers.com, accessed May 5, 2019, http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397346/shina_inoue_kan_1949/; “Shina Inoue Kan 1955,” Newspapers.com, accessed May 5, 2019, http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397477/shina_inoue_kan_1955/; “Shina Inouye 1922,” Newspapers.com, accessed May 5, 2019, http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397268/shina_inouye_1922/; “Shina Kan 1950,” Newspapers.com, accessed May 5, 2019, http://www.newspapers.com/clip/25397651/shina_kan_1950/.

[9] See United Methodist Church, “Rev. Elsie F. Stowe Spring 2011,” accessed May 3, 2019, https://www.nyac.com/revelsiefstowespring2011. Reverend Stowe’s papers are housed at the United Methodist Christman Archives in White Plains, NY.

[10] “Yale Divinity School’s Women’s History Project” (n.d.), Yale University Divinity School memorabilia collection RG 53 Series VI Box II, Yale Divinity Special Collections, 2.

[11] Ibid., 3.

[12] “First Women of YDS,” Yale Divinity School, accessed April 14, 2019, https://divinity.yale.edu/gallery/first-women-yds.