Nathan Empsall ’19 M.Div. is one of six dual-degree students at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and Yale Divinity School, where he is also earning a diploma in Anglican Studies at Berkeley Divinity School at YDS. He recently completed a survey of more than 100 randomly selected Episcopal congregations from across the country, attempting to gauge churches’ level of engagement with creation care and climate change. He has presented his findings at several academic conferences as well as to the Episcopal Church’s Task Force on Care of Creation and Environmental Racism, of which he is a member.

YDS interviewed Empsall about his survey and related projects.

What motivated you to undertake this survey?

According to the Pew Research Center, only 22 percent of church-goers report hearing about the environment in church. I wanted to find out what challenges or objections prevent churches from starting creation ministries. My hope is that the survey’s findings will be useful to environmental communicators and theologians, helping them craft resources that meet parishes where they are.

According to the Pew Research Center, only 22 percent of church-goers report hearing about the environment in church. I wanted to find out what challenges or objections prevent churches from starting creation ministries. My hope is that the survey’s findings will be useful to environmental communicators and theologians, helping them craft resources that meet parishes where they are.

Who responded to the survey?

Just over 100 parishes submitted responses. I have numbers from the first 92, although I still need to add data from a few late responses. One person responded on behalf of each congregation—mostly clergy, but some lay leaders too. The responses were from every part of the country and were split pretty evenly between rural, urban, suburban, and small towns. The demographics were fairly reflective of the denomination as a whole.

What environmental actions did you find churches are the most excited about?

Seventy-one percent of parishes said they’re engaged in “general stewardship (recycling, CFL lightbulbs, non-disposable coffee mugs, etc.).” It’s exciting to see that most churches are willing to take at least small steps.

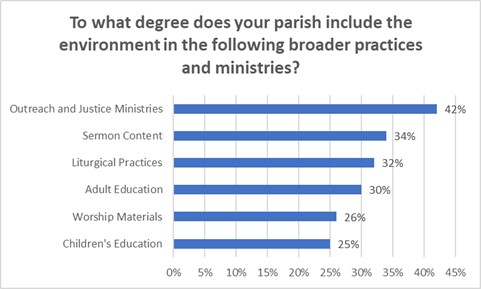

Forty-two percent of parishes said they regularly include the environment in existing outreach and justice ministries. However, when asked what inspires them to do environmental work, “environmental justice” actually came in last. I assume this means churches simply don’t understand the links between the environment, poverty, and racism.

Forty-two percent of parishes said they regularly include the environment in existing outreach and justice ministries. However, when asked what inspires them to do environmental work, “environmental justice” actually came in last. I assume this means churches simply don’t understand the links between the environment, poverty, and racism.

Next on the list was getting outdoors, with 40 percent of churches saying they do it regularly.

How often do congregants hear about climate change in sermons?

Only 34 percent of churches said the environment is frequently part of their sermons, yet most also said that their parishioners understand the connection between faith and the environment. This prompts a question: Where would most people have learned about that connection if not from their pastors? To that end, other research I’ve seen shows that most volunteer-led environmental ministries begin after receiving theological encouragement from the pulpit.

What are the challenges churches report facing in trying to do more of this work?

Fifty-eight percent of churches said they face “too many other competing events, demands, or priorities.” An overlapping 58 percent also reported some form of “survival mode,” meaning they selected at least one of three other options: “not enough lay leaders or volunteers,” “not enough active members,” and/or “financial/budgetary challenges.” Basically, “being green” is seen as just one more thing to do at a time when churches already feel strapped.

In your presentations, you make a distinction between viewing environmental action as a “lens” and seeing it as an “issue.” What is the difference, and why would we want to see a shift to environment as lens?

From our food to our building materials, everything comes from the environment, and from public health to racism and poverty, every issue is impacted by climate change. That means the environment has to be how we look at the world, not what we look at—a lens on other issues.

From our food to our building materials, everything comes from the environment, and from public health to racism and poverty, every issue is impacted by climate change. That means the environment has to be how we look at the world, not what we look at—a lens on other issues.

Asked if the environment is a part of other issues, 76 percent of churches say it is, but I’m not sure we’ve taken that message to heart. Fifty-eight percent of churches say there are competing priorities, but if the environment is a part of every priority, what’s the competition?

We don’t need “green teams.” Creation care can simply be part of all the things we’re already doing, from maintenance to Sunday School to serving local food and less meat at parish events.

To what extent do churches avoid talking about the environment because of the politics involved?

To my surprise, only 21 percent of churches said “The environment is seen as political and we want to avoid controversy.” Perhaps some clergy object to specific political activities, like contacting Congress, but they understand they can still lead nature walks or install solar panels. Perhaps some are willing to talk about nature generally, but not climate change specifically. Or maybe politics really isn’t the issue after all!

This survey was only of Episcopal churches. Do you think its findings can be relevant for other denominations?

Absolutely. The Episcopal Church is similar in culture and theology to other mainline Protestant denominations, which also face “survival mode.” I know our worship in Episcopal churches reminds many people of the Roman Catholic Church as well.

Moving beyond the survey, the political dynamics around climate change seem like a frustrating stalemate to many people. Is society as stuck as we seem?

Gallup recently found that two-thirds of Americans understand the globe is warming because of human activity. It’s not society that’s stuck—it’s our system. Americans are ready for action on climate change, but we won’t see that action until we deal with gerrymandering, fossil-fuel money in politics, antiquated models of representation, and attacks on minority voting rights. It’s up to the people to make sure those systems change. And even after working in Washington, D.C. for years, I still have hope.

What role can churches play in addressing this challenge and galvanizing society-wide – even global – action?

My survey asked what motivates people to do this work. Seventy-four percent said they want to care for God’s creation, and 62 percent said they want to connect to God through nature. In other words, people are inspired by the beauty of creation, and by the desire to connect to something larger than themselves. That kind of connection, as well as the hope of the resurrection, are powerful things the church can offer.

The Episcopal Church is 49 percent Democratic and 39 percent Republican – and despite those differences, we’re still worshipping together. We’re still talking. Church can be a place where we have important and hard conversations about the moral issues facing society. It’s when we have those personal conversations that things start to change.

You launched and continue to operate Episcopal Climate News. Tell us about that project.

Even if creation-care ministries aren’t typical, there are still a lot of them! In the Episcopal Church alone, official delegations have gone to U.N. climate conferences, our General Convention has passed dozens of environmental resolutions, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants have gone to local projects. Our Church Pension Fund just invested $40 million in clean-energy infrastructure.

Episcopal Climate News tries to bring all these stories into one place, highlighting the spiritual and social-justice sides of climate change. We also share scientific and mainstream news articles to help keep the church informed. In just under a year, we’ve gotten more than 2,300 “likes”! Check us out at episcopalclimatenews.com/ or facebook.com/EpiscopalClimateNews/

What do you plan on doing after graduation?

Sleep and play video games. Oh, sorry, you meant after that!

God willing, I’ll be ordained a priest in June. Before I came to Yale, I worked as an online organizer for progressive causes. I’m going to continue that work, but now from a faith-based perspective, running campaigns for a small advocacy non-profit. I’ll also work as a parish priest part-time.

RELATED CONTENT: Read Dean Greg Sterling’s commentary in Sojourners, “The greatest environmental pollutant is our politics.”