By Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R.

Among its numerous and far-reaching effects, the Coronavirus pandemic compelled many to reassess the directions of their lives. This “Covid pivot” inspired new identities for people of all description: the aquarium keeper who became a “death doula”; the insurance salesman who transformed into a landscape gardener; the wedding planner who opened her own editing service. For Khaleelah Harris ’21 M.A.R., last year’s lockdown led her from thoughts of ministry and a Master of Divinity to becoming an artist and historian with a powerful social vision.

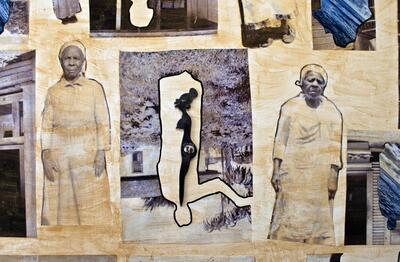

Harris’s collage work is part of an exhibition she co-curated that runs through January at Yale Divinity School. The show, Allegories, Renditions, and a Small Nation of Women, brings together 16 artists working in collage and mixed media to explore how Black women enlisted Christianity to forge their identities in a context of racism, social change, and cultural migration.

Harris’s collage work is part of an exhibition she co-curated that runs through January at Yale Divinity School. The show, Allegories, Renditions, and a Small Nation of Women, brings together 16 artists working in collage and mixed media to explore how Black women enlisted Christianity to forge their identities in a context of racism, social change, and cultural migration.

Harris was halfway through her Yale M.Div. when the shutdown separated her from classrooms and classmates. Her divinity school experience had been defined by her coursework with Prof. Willie Jennings on the intersection of race, theology, and liberation. “In each course,” she recalled during a recent telephone conversation, “he said things that opened my mind.”

Under Covid, with all the academic rules in flux, and having lots of alone time, Harris began an independent reading program on how the story of African-American women could be told more truthfully.

Her reading led her to scholars of Black women’s history, literature, and sociology. By far the most influential title was Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals, by Saidiya Hartman ’92 Ph.D. In her book, Hartman, a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, enacts what she describes as “critical fabulation,” a writing methodology “that combines historical and archival research with critical theory and fictional narrative.”

As the subtitle suggests, Wayward Lives presents “intimate histories” of Black women (and some men), including historical figures like Ida B. Wells. Mostly, though, Hartman’s focus is on young women whose existence is fictional, but whose truth, she avers, can be reasonably accepted as literal. Critical fabulation is a tool the scholar and author uses to recover “absent voices” that are latent in archives created in a system of white hegemony. “I think of my work as bridging theory and narrative,” she noted in an early essay outlining her theory.

Hartman’s work touched a chord in Harris. She’d grown up in southern Florida and earned a B.A. in religion and philosophy from Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, starting at YDS immediately after finishing her undergraduate studies. The summer after her first year at Yale, she was a research fellow at the W.E.B. Du Bois Center at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

On her website now, Harris lists research interests including 19th and 20th Century African-American Women’s Cultural History; race, gender, and the Black middle class; W.E.B. Du Bois; and African American religious thought and freethought. She is currently studying history in a master’s degree program at Howard University.

Harris had taken a few art classes as a child, but she’d not made art for many years. Hartman’s book led her to return to her creative roots and begin making collages.

Harris had taken a few art classes as a child, but she’d not made art for many years. Hartman’s book led her to return to her creative roots and begin making collages.

“I got back into the art once I noticed the similarities between collage and critical fabulation,” she said. Just as Hartman’s fictive profiles are assembled through a process of composite research and conception, the essence of collage is the combination of disparate visual elements to form a unified picture. The juxtaposition of otherwise unconnected visual cues sparks associations that arc across the image, conjuring new meanings in the viewer. Harris used collage’s inherent power of suggestion to create richer identities for Black ancestors and to reanimate lives that were “intentionally hidden.”

“That is collage art,” said Harris. “It’s about discovery, recovery, filling in the blanks. As I began doing my own research on particular sects of African-American women, I noticed there were very few photographs, and for some women, there are no pictures.” Given the importance of visual evidence in the historical narrative, she continued, “I wanted to do with images what Professor Hartman had done with her words.”

Specifically, her interest focused on African-American church women from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, a period of spreading Jim Crow violence and Black migration from the rural South to industrialized Northern cities. The Black Christian church played a key role in educating and empowering one-time enslaved peoples and their descendants. Harris created a series of “portraits” of the “small nation of women” who, though central to the church’s history, were often erased from the visual record.

She launched an Instagram page to display her work and quickly attracted the attention of like-minded artists. The idea for mounting the current exhibition was born in the spring of 2021, as Harris was completing her YDS studies after transferring to the Master of Art in Religion track. Having become part of a diverse, worldwide culture of collage artists, she began to wonder how others would interpret the subject matter she was committed to.

With co-curator Teri Henderson of the Black Collagists Incubator, Harris posted a call for entries for works exploring “The Makings of a Race Woman: Christian Identity & Assimilation.” Artists from as far away as Australia responded. The resulting exhibition is now on display in the Sarah B. Smith Gallery, just inside the main entrance of Yale Divinity School.

Allegories, Renditions, and a Small Nation of Women can be viewed as a triumphant family album of Black Christian women, a gathering of unsung heroines joined in faith to transcend the cruelty, indignity, and forced anonymity of racism. The 33 photo-based collages are augmented by acrylic paint, watercolor, ink and gold foil, and found objects ranging from old letters and other text fragments to lace and plastic swizzle sticks. Some women depicted in the show present themselves in the elegant high-collared dresses and feathered hats that marked high fashion a century ago, while others wear plainer clothes, including the shapeless frocks and bandanas of women in service.

Allegories, Renditions, and a Small Nation of Women can be viewed as a triumphant family album of Black Christian women, a gathering of unsung heroines joined in faith to transcend the cruelty, indignity, and forced anonymity of racism. The 33 photo-based collages are augmented by acrylic paint, watercolor, ink and gold foil, and found objects ranging from old letters and other text fragments to lace and plastic swizzle sticks. Some women depicted in the show present themselves in the elegant high-collared dresses and feathered hats that marked high fashion a century ago, while others wear plainer clothes, including the shapeless frocks and bandanas of women in service.

Nature imagery is a recurring metaphor, both of beauty and spiritual ascent. Ten of the pictures incorporate images of flowers, four contain butterflies, three include birds or wings. Twiggy Boyer’s roundel Flowers in the Garden shows a pair of young women surrounded by a paradise of daisies and other blooms. The work’s overlapping layers of paper fragments, some photographic, some drawn or painted by the artist, create a densely textured Eden.

The exhibition’s theme of religious identity naturally invited frequent riffing on Christian motifs. Trinity, by Jessica Whittingham, sets a trio of elegantly formal women against an ornate gilded iconostasis, a screen found in Orthodox churches containing the icons of saints. Here, the images are of powerful Black women, including Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. Similarly, the central female figure in Melissa Sutherland-Moss’s Undeniable Trinity is repeated three times, becoming mother, daughter, and guiding spirit to the 1960s-era Black Power activists who trail in the hem of her skirt.

Emily Marbach creates an ambivalent portrait with Matti as Mother Mary. The sepia face of a pensive young woman gazes out at the viewer, while the figure’s dark hands, taken from a black-and-white photograph, cradle what appears to be a white child. A take on the Eastern European image of the Black Madonna (complete with halo), the work also comments on the paradox of Black Christianity in a country that typically depicts Jesus as white.

Black fractured identity is explored by Sameena Sitabkhan in a pair of portraits constructed from torn and recombined photographs. There’s an unsettling eros to Faceted, where a black-and-white image of a woman wearing the stereotypical white head scarf of a domestic (or, earlier, a “house slave”) collides with a color fragment of a bared Black shoulder, neck, and gold earring. The artist’s Mary Ellen renders a woman’s face as a sort of mask of its own authenticity, literally stitched together with red embroidery thread.

Black fractured identity is explored by Sameena Sitabkhan in a pair of portraits constructed from torn and recombined photographs. There’s an unsettling eros to Faceted, where a black-and-white image of a woman wearing the stereotypical white head scarf of a domestic (or, earlier, a “house slave”) collides with a color fragment of a bared Black shoulder, neck, and gold earring. The artist’s Mary Ellen renders a woman’s face as a sort of mask of its own authenticity, literally stitched together with red embroidery thread.

Artist as well as curator, Harris confronts the idea of disguise and impersonation in her work When I Was a Child, an image of a melancholy Black girl holding a Caucasian mask.

As a white male who grew up in the 1960s, I was continually challenged by the exhibition to reckon with questions of culpability and complicity. But more than embarrassed white guilt, the issues grappled with in the show elicited the compassion, grief, and revulsion any empathetic individual must feel observing the virulence of white privilege.

Three works by CoCo Harris drove home these sensations like spikes. Meticulously crafted photo collages encased in resin, the works are visually diverse, ranging from imagined heavens to the legacy of slavery, but linked by the inclusion in each of so-called “Zulu Lulu” swizzle sticks. These black plastic drink stirrers, remnants of the 1960s, are appalling, dehumanizing caricatures of African women depicted in silhouette. Artist Kara Walker has used silhouetted racist tropes to great effect, but her work sets those clichés at an ironic critical distance. Harris’s collages offer no such remove; the sickening actuality of her artifacts bear witness to the sin of white supremacy, made more brutal by being so casual.

As exhibition organizer, Khaleelah Harris found the variety and intensity of the art she elicited a revelation.

“I didn’t have that much experience around collage, so coming into this kind of art and into these interpretations has been beautiful and overwhelming at the same time,” she said. “Overwhelming because it’s giving me the same feeling when I’m reading text research [about Black history]. I’ve never had that experience looking at art before.”

The artworks reveal a sophisticated understanding of the role and identity of woman in the Black church.

“You can tell that some [of the artists] already understand the way that Christianity and Christian identity can be used by people to succeed and get farther along in this country. They understand that historically for African-American women, religion has helped them get along [and] survive.”

The exhibit evokes a period roughly from the 1880s through the 1910s and expresses the quest for dignity that Black women engaged in, using Christianity as their idiom. “Everybody was trying to figure out how they could gain citizenship,” Harris observed. “The sons and daughters of slaves were figuring out how they could be considered respectable citizens.”

The exhibit evokes a period roughly from the 1880s through the 1910s and expresses the quest for dignity that Black women engaged in, using Christianity as their idiom. “Everybody was trying to figure out how they could gain citizenship,” Harris observed. “The sons and daughters of slaves were figuring out how they could be considered respectable citizens.”

Christian conformity became a way of modeling white bourgeoise values. Grooming, jewelry, clothes, and Christian symbols—being seen in one’s “Sunday best”—became ways of refuting the degrading image of Blacks that permeated white culture. “If these practices could in some way let people know that ‘Hey, I’m a moral being,’ they were going to be utilized,” said Harris. “You notice [in the artworks] that there are cross necklaces, cross earrings, as well as white dresses, particular hairstyles, and hair jewelry.”

It was virtue signaling as a survival tactic.

“The whole purpose of my exhibit is to talk about Christianity as social capital,” Harris explained. Her work interrogates a stereotype “that Black people are inherently religious, or that they take religion the most seriously, or that they practice Christianity the best or with the most integrity.”

“At the end of the day, Black people have to live in America, and in America, Christianity hasn’t always been [only] about actual faith practice,” she said. “It’s been about a whole lot of other things, and to deny Black [women] engagement with that kind of experimentation is ultimately to deny them some humanity. It’s also to deny them a level of intelligence and their recognition of politics in America.”

“At the end of the day, Black people have to live in America, and in America, Christianity hasn’t always been [only] about actual faith practice,” she said. “It’s been about a whole lot of other things, and to deny Black [women] engagement with that kind of experimentation is ultimately to deny them some humanity. It’s also to deny them a level of intelligence and their recognition of politics in America.”

Harris’s work, and her exhibition, interrogate the church as a site of Black women’s radical identity formation. “They saw what was going on and said, as a means of survival, ‘Okay, noted.’”

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. writes on religion and art.