By Ray Waddle

Pay attention, urges professor Vasileios Marinis ’03 M.A.R. Slow down and look, he says. Stop and behold. Linger and decode, whether it’s an icon, a church, a printed page, or the natural world outside. Discover something life-enhancing in the focus on a particular image or text amid the unprecedented blur and clutter of messages that define contemporary life.

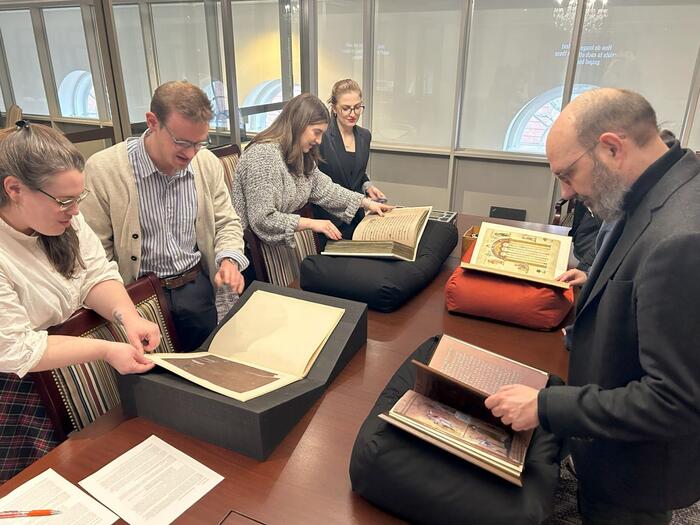

“What I try to convey to my students, if nothing else, is the joy of looking attentively, the joy of discovery and understanding what you are seeing,” says Marinis, Professor of Christian Art and Architecture at YDS and the Yale Institute of Sacred Music.

“What I try to convey to my students, if nothing else, is the joy of looking attentively, the joy of discovery and understanding what you are seeing,” says Marinis, Professor of Christian Art and Architecture at YDS and the Yale Institute of Sacred Music.

“In 20 years you might not remember our class discussion of Hagia Sophia or Justinian, but I hope you’ll remember how to pay attention to a church interior, how it feels to enter it, what you see when you look around. It’s the same with a painting. Very often in museums we spend a couple of seconds with a work of art and move on. Try looking at fewer images but spending more time with each of them. Think about what the work is trying to tell you. That’s more rewarding than taking two seconds with whatever’s in front of you.”

That breakthrough moment

This applies to books, texts, and stained-glass windows, or, for that matter, advertisements and billboards, he said. It’s worth the effort to break through to that moment when you’ve grasped an author’s message, intention, ideological agenda, or emotional effect.

“Our students in general are very good at paying attention, but sometimes, after orientation, they tell me the one thing they’re hearing is to skim through the assigned texts—this is terrible advice!” Marinis said. “I remind them that their YDS experience is one of the few times in life when they can dedicate time to reading closely. Sometimes a text might be difficult or boring—I understand that—but there’s joy and surprise in learning how an author constructs a sentence or builds an argument, even if you don’t like what is being argued. You can’t get that by skimming.”

Born and raised in Greece, Marinis has been teaching at YDS since 2010. Recently he had a role in the Divinity School’s sponsorship of the new “Prodigal Son” icon that now hangs in the Henri Nouwen Chapel in the YDS library. Marinis recommended iconographer George Kordis to create the piece, which was installed in January. Kordis is widely celebrated for working within Byzantine traditions of iconography yet demonstrating flourishes of personal spirit and faith. In his long career, Kordis has managed to break free from merely copying older models, a dictate that held sway in the Greek arts establishment foe decades, Marinis said. The Nouwen Chapel icon embodies some of the artist’s innovations.

Art and ambiguity

The power of such a work is measured by the emotional surprises it stirs, the spiritual entry points it offers, and the ambiguities it raises, he said.

“It’s a sign of a successful image if it raises questions but doesn’t immediately answer them.”

Editor’s Note: A full article on the new icon will be featured in YDS ‘Notes From the Quad’ this spring.

Then there is the matter of venerating an icon, compared to gazing at a painting. Icon veneration aims to create a dynamic sacred connection between the image and the viewer, Marinis suggested.

“When a person venerates an icon, they do not venerate the wood or the pigments, but the prototype of the image, to whom the veneration is transferred, in this case, Christ. This relative veneration of the icon and saints is different from the genuine veneration of the person depicted.”

A desert adventure

Earlier this year, Marinis gave 11 Yale students a chance to immerse in the devotional world of iconography when he and the group traveled to the Sinai peninsula in Egypt to visit a working monastery that’s about 1,500 years old. Situated at the base of Mt. Sinai, St. Catherine’s is the oldest continuously functioning Orthodox monastery in the world. It is home today to about 20 monks—and to thousands of icons that have accumulated there over the course of 15 centuries, often as gifts from artists or visitors.

“It’s an amazing collection, some very fine icons, and there’s an astonishing library as well,” Marinis said. “We talked about the architecture. We attended daily services. This included the Christmas vigil around midnight when the church interior was gradually illuminated by candlelight, and out of the darkness you suddenly saw the figures of countless icons coming out of the shadows, appearing almost to move. It was amazing to see the icons not just as works of art but as objects inhabiting a living space. We wanted students to experience all this in a functioning monastery.”

A byzantinist is born

A byzantinist is born

Growing up in Greece, Marinis had encounters with icons, mosaics, and murals from early on. As a youth, he visited the 1,000-year-old Hosios Loukas monastery near Distomo, learning how declarations of Christian faith were animated in the colors, paint, fabric, wood, and stone of the art adorning the daily worship spaces of a monastic community. His vocational dream to be an art historian—specifically, a byzantinist—was launched. He received a B.A. from the University of Athens and a graduate degree from the University of Paris. Before he finished his Ph.D. in art history at the University of Illinois, he enrolled at YDS for an M.A.R. degree in order to go deeper into the history of liturgy.

His books include Architecture and Liturgy in the Churches of Constantinople (Ninth to Fifteenth Centuries) (Cambridge University Press, 2014) and Death and the Afterlife in Byzantium: The Fate of the Soul in Theology, Liturgy, and Art (Cambridge, 2017). The latter study still inspires inquiries from readers hoping to get the inside intel on what happens after death. Marinis counsels caution about embracing imaginative ideas from the medieval world about souls being harrowed by demon-occupied toll houses or elaborate circles of hell.

‘Just read Matthew 25’

“I’m interested in these themes as a historian of culture, but some of these ideas create a lot of anxiety with people today and are not very helpful. I say, just read Matthew 25. All you need to know about the afterlife in Christianity is found in that chapter.”

The enterprise of paying attention thus has broad ramifications for the life of the spirit as well as for art, he said.

“An attentive reader is also an attentive listener. An attentive listener is more likely to become a better citizen. Again, if my students remember when Hagia Sophia was built, that’s great, but the point is to make the choice to be more observant and find joy in understanding and become better equipped to be a better person.”