By Dr. Moses Moore ‘77 M.Div.

The social and political activism of contemporary clergy such as the Rev. William Barber illuminates the “applied Christianity” that marked the ministry and legacy of Henry H. Proctor 1894 B.D. Proctor’s efforts place him in a long lineage of Black reform-minded attendees of YDS which began in the mid-nineteenth century with the abolitionist activism of the Rev. James W. C. Pennington and has extended into the twenty-first century. Moreover, Proctor’s prophetic vision and accompanying ministry arguably made him one of the most prominent Black YDS alumni of the early twentieth century and placed him in the vanguard of one of the nation’s most innovative religious-based reform efforts—the social gospel movement.

Roots

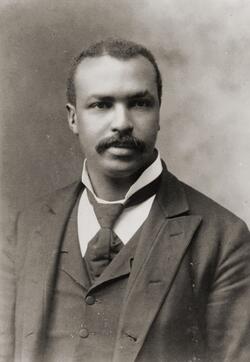

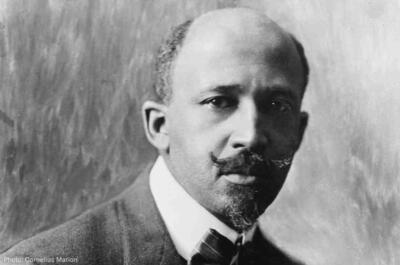

Born to former enslaved people near Fayetteville, Tennessee, on December 8, 1868, Proctor’s religious and theological lineage included the rural southern Black Methodist piety of his parental home and youth; a reform-oriented evangelicalism imbibed during seven years of study at Fisk University (where he was a classmate of W.E.B. Du Bois); and the emergent, socially engaged theology of Protestant liberalism that he embraced as a student at Yale Divinity School. This diverse theological lineage would subsequently be refined and adapted over the course of his almost forty-year ministry in the Congregational Church.

Born to former enslaved people near Fayetteville, Tennessee, on December 8, 1868, Proctor’s religious and theological lineage included the rural southern Black Methodist piety of his parental home and youth; a reform-oriented evangelicalism imbibed during seven years of study at Fisk University (where he was a classmate of W.E.B. Du Bois); and the emergent, socially engaged theology of Protestant liberalism that he embraced as a student at Yale Divinity School. This diverse theological lineage would subsequently be refined and adapted over the course of his almost forty-year ministry in the Congregational Church.

Proctor’s matriculation at Yale Divinity School was essential in shaping his subsequent ministerial activism.

As a student from 1891 to 1894, he studied under scholars who strove to clarify the issues and challenges presented to their faith and theology by the era’s new scientific and intellectual currents. Their responses made Yale Divinity School one of the seedbeds of the “New Theology” of Protestant Liberalism. Notably, the theological transformations taking place at the Divinity School were accompanied by courses that exposed Proctor and his classmates to the methodologies and insights of emergent disciplines such as comparative religion, biblical criticism, philosophy of religion, and sociology. The school’s growing concern for the social application of Christianity was evident in its addition of a course on “social ethics” to the curriculum during Proctor’s first year of study.

Also significant was Proctor’s public recollection that at Battel Chapel and local churches “presided over by Munger and Smyth…Phillips, Tywitchel [Twichell], Luckey, . .” and “Albert P. Miller” (one of YDS’s first Black graduates (1885) and pastor of Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church), he and other YDS students had been given the opportunity to hear some of the most progressive and “ablest preachers of the country.”

Even as a student at Yale, Proctor began appropriating his new academic and theological skills and insights in exploration of his Black religious heritage. Two papers he authored during the course of his studies had special implications for his unique theological synthesis and orientation.

One was a pioneering examination of “The Theology of the Songs of the Southern Slaves” in which he “tried to show how the slaves built their songs on a real theological system.” His continued exploration of the dialectic of race and theology also resulted in a Graduation Day address titled “A New Ethnic Contribution to Christianity” in which he argued that “in the historic development of Christianity, race and religion have had a reciprocal relation.” This provocative and prophetic thesis provided additional warrant for Proctor’s subsequent efforts to develop a progressive and socially active ministry that was attuned to the rapidly changing needs of the Black community at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Insights gleaned from Proctor’s broader studies at Yale would also have significant impact as he began to forge a theological synthesis that would provide a cogent and compelling rationale for an intellectually progressive, socially active, and racially aware ministry. His efforts place him among a small cadre of Black theological liberals that at the turn of the century included Reverdy Ransom, William De Berry, Richard R. Wright, Jr., and Jesse E. Moorland. All would selectively appropriate and employ the tenets and methodologies of the “New Theology” in their efforts to forge ministries responsive to the challenges facing the Black church and community at the cusp of the twentieth century.

“The lure of the New South”

Upon graduation from Yale Divinity School in 1894, Proctor responded to “the lure of the New South” when he accepted the call to Atlanta’s First Congregational Church and became its first Black minister. There, amid the urban, industrial, and racial sprawl of bustling Atlanta, he began to forge an expansive ministry that would be both spiritually and socially relevant.

He was fortunate to have the assistance of his new bride, Adeline L. Davis, who had met Proctor while a student in Fisk’s Normal School, and soon aborted plans to become a foreign missionary in order to marry him in 1893. Her life and work independently and in support of Proctor’s ministry illuminates the often-overlooked contributions of numerous Black women to the emergent social gospel movement.

He was fortunate to have the assistance of his new bride, Adeline L. Davis, who had met Proctor while a student in Fisk’s Normal School, and soon aborted plans to become a foreign missionary in order to marry him in 1893. Her life and work independently and in support of Proctor’s ministry illuminates the often-overlooked contributions of numerous Black women to the emergent social gospel movement.

With the assistance of Adeline, Proctor, a gifted preacher and organizer, quickly doubled First Congregational’s membership and, building upon the church’s long tradition of missionary activism, extended its ministry to include not only a temperance society but also a Christian Endeavor Society, a Working Men’s Club, a Women’s Aid Society, a Young Men’s League, and a prison ministry.

Proctor additionally served notice that local and state politics came within the purview of his expanding ministry as he joined former Fisk classmate W.E.B. Du Bois, John Hope, and other Black Atlanta leaders in opposition to white efforts to disenfranchise Black Georgians. Arguing that the church as a whole must be “an institution for social betterment,” he challenged the city’s other churches and ministers to make social salvation as much a part of their agenda as soul salvation. Notably, among Black clergy who shared his agenda to varying degrees was A. D. Williams, the newly installed minister of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Church and maternal grandfather of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Within a decade of accepting his call to First Congregational Church, Proctor succeeded in forging an impressive model of socially applied Christianity. Thus, Ernest Hamlin Abbott, the influential editor of The Outlook, observed in 1902 that First Congregational had ministerial and social service features unheard of in a church program in the South and that it was one of the region’s “most progressive and best organized “churches, “white or black.” Proctor’s success and growing fame as a minister of applied Christianity was also attested to by W.E.B. Du Bois, his former Fisk classmate, in his 1903 Atlanta University study of “The Negro Church,” and by Atlanta’s Clark University, which granted Proctor an honorary doctorate in 1904.

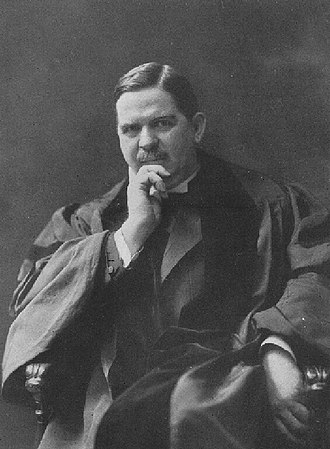

But Proctor’s ministerial efforts were not limited to Atlanta or the geographical boundaries of the United States. Committed to extending the “Kingdom of God” both at home and abroad, he made Southwest Africa a special focus of his expanding ministry and succeeded in encouraging the establishment of the Galangue mission in Angola. Of key importance nationally was his role in the establishment in 1903 of the National Convention of Congregational Workers among Colored People. As founding president and subsequently secretary of this organization, Proctor encouraged a more progressive and activist ministry among Black Congregationalists dispersed throughout the nation. His increasing prominence as a pulpit orator and a social gospel activist also resulted in speaking invitations throughout the nation and association with renowned clergy such as Washington Gladden, who is heralded as “the father of the Social Gospel Movement.” Proctor’s ministerial and social gospel bona fides received additional confirmation when he was elected assistant moderator of the National Council of Congregational Churches by “unanimous vote” in 1904

But Proctor’s ministerial efforts were not limited to Atlanta or the geographical boundaries of the United States. Committed to extending the “Kingdom of God” both at home and abroad, he made Southwest Africa a special focus of his expanding ministry and succeeded in encouraging the establishment of the Galangue mission in Angola. Of key importance nationally was his role in the establishment in 1903 of the National Convention of Congregational Workers among Colored People. As founding president and subsequently secretary of this organization, Proctor encouraged a more progressive and activist ministry among Black Congregationalists dispersed throughout the nation. His increasing prominence as a pulpit orator and a social gospel activist also resulted in speaking invitations throughout the nation and association with renowned clergy such as Washington Gladden, who is heralded as “the father of the Social Gospel Movement.” Proctor’s ministerial and social gospel bona fides received additional confirmation when he was elected assistant moderator of the National Council of Congregational Churches by “unanimous vote” in 1904

“The church that saved a city”

Despite the initial success of Proctor’s ministry, the Atlanta riot of 1906, a convulsion of racial violence that shocked both Atlanta and the nation, painfully illuminated both the limitations of his evolving ministry and the magnitude of the problems confronting him and other progressive ministers.

Ironically, the riot provided inspiration and opportunity for Proctor to develop a full-blown social gospel ministry aimed at mitigating the conditions that contributed to Atlanta’s racial conflagration. His activity in the immediate aftermath of the riot illuminates an emphasis upon interracial cooperation and racial reconciliation that would become one of the defining characteristics of his evolving social gospel ministry.

As Atlanta’s embers cooled, Proctor took the lead in establishing an interracial coalition of prominent Black and white clergy, educators, and civic leaders who were determined to ease racial tensions and address the causes of the riot. His efforts contributed to the founding of Atlanta’s famed Interracial Commission, heralded as one of the organizational pioneers of the modern civil rights movement.

Notably, the Commission’s statement of purpose reads in part like a preliminary social gospel manifesto:

We, a group of Christians, deeply interested in the welfare of our entire community, irrespective of race or class distinction, and frankly facing the many evidences of racial unrest, which in some places have already culminated in terrible tragedies, would call the people of our beloved community to a calm consideration of our situation… . Conscious of the responsibility which a Christian democracy imposes upon self-reassuring and self-governing citizens, let us strive to meet our obligations in the spirit of Jesus Christ … . If religion stops at individual petition, it can attain no salvation … . Christianity, in its essence, is the Son of Man dying upon a cross for all men; and its challenge to men is the call of that cross to sacrificial service in fellowship with one another.

Although Proctor’s role in the authorship of this progressive affirmation of applied Christianity is unclear, it exudes his theological convictions and commitment to interracial Christian activism. It is also notable that his labors in the wake of the riot inspired a literary tribute that lauded him and proclaimed First Congregational “The Church That Saved a City.”

Amidst the ruins of the riot, Proctor was convinced that an even more expansive expression of “applied Christianity” could help provide an antidote to the volatile social and racial conditions that plagued Atlanta. Confident that “the first step in this direction was to secure a church building adapted for the purpose,” he set out to build a new church—an institutional church, offering social, welfare, and cultural programs to the Black community as well as a ministry of racial reconciliation to the broader community.

By the fall of 1907, Proctor was engaged in an ambitious fundraising campaign that effectively capitalized on the shock and concern elicited locally and nationally by the riot. Armed with letters of recommendation from influential Blacks and whites, he successfully campaigned throughout the nation for funds.

Among the more influential letters of recommendation in his possession was one authored by Booker T. Washington. An appreciative Proctor invited Washington to serve as guest of honor at groundbreaking ceremonies for the new edifice.

Washington’s support of Proctor’s agenda was consistent with his similar critique of the traditional Black church and ministry and his often-expressed view that a new style of Black church and clergy was necessary in order to address the needs of the Black community in the post-Reconstruction era. It was a message that made Washington a frequent speaker at First Congregational and a welcomed visitor to its parsonage.

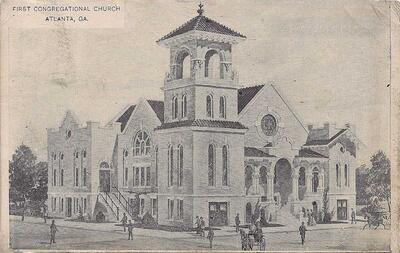

In early December of 1908, the new “institutional church” at the corner of Houston and Courtland Streets was dedicated. Appropriately, famed social gospel activist and Proctor associate Washington Gladden was invited to give the dedicatory address. Although Gladden was unable to attend, the event garnered notice from even the racially recalcitrant Atlanta Constitution, which reported that it marked “the official opening of the first genuinely institutional church of this race in the southern states” and that as a “valuable extension” of First Congregational’s “field of activity” it would “provide for the entire Negro population of this city means for self-improvement and social intercourse heretofore completely lacking.”

In early December of 1908, the new “institutional church” at the corner of Houston and Courtland Streets was dedicated. Appropriately, famed social gospel activist and Proctor associate Washington Gladden was invited to give the dedicatory address. Although Gladden was unable to attend, the event garnered notice from even the racially recalcitrant Atlanta Constitution, which reported that it marked “the official opening of the first genuinely institutional church of this race in the southern states” and that as a “valuable extension” of First Congregational’s “field of activity” it would “provide for the entire Negro population of this city means for self-improvement and social intercourse heretofore completely lacking.”

Proctor had worked intimately with the church’s architect to design a building that encompassed his vision of a socially aware and active Christianity. Reasoning that since the ministry of Christ had been holistic and “threefold” in its scope—addressing the needs of the mind, spirit, and body—he argued that the church must likewise appeal to and serve the whole man.

The result was an attractive two-story structure of Spanish Mission design that included an auditorium, a gymnasium, a library, sewing rooms, and a kitchen. Consequently, the new edifice and its expansive ministry were hailed by Proctor as the model of a “New Type of Church,” an “industrial temple,” fully attuned to the modern needs of the race. In it, he exclaimed, “we dedicated the pulpit and the parlor, the auditorium and the organ, the dumb-bell and the needle, the skillet and the tub, to the glory of God and the redemption of a race.”

The church’s innovative design and expansive ministry attracted a growing list of distinguished visitors who Proctor would host at his new “Industrial Temple.” Among them were Presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. It also attracted some of the era’s most prominent clergy, including T. D. Talmage, Samuel Parkhurst, and Russell Conwell, who concurred in the assessment that First Congregational was “the most progressive church … in the South.”

The church’s innovative design and expansive ministry attracted a growing list of distinguished visitors who Proctor would host at his new “Industrial Temple.” Among them were Presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. It also attracted some of the era’s most prominent clergy, including T. D. Talmage, Samuel Parkhurst, and Russell Conwell, who concurred in the assessment that First Congregational was “the most progressive church … in the South.”

Visitors to First Congregational were often impressed with another innovative component of Proctor’s expansive ministry—the Avery Home for Working Women.

Established next to the parsonage, the Home provided shelter for Black women who had migrated to Atlanta from rural areas and often found their plight even more desperate than that of their male counterparts. Reflective of this reality and need, Proctor proclaimed that it was “the first home in the world opened by any church for colored girls” whom he described as “the most unprotected … in all the world.”

Proctor was also committed to using his expansive ministry to address what he euphemistically referred to as “the South’s great unsolved problem.” Heretofore, he noted, “the religion of the South” had been “sentimental rather than practical, individual rather than social.” But, he argued, “Hitch up the religion of the South to its great unsolved problem, and a new day will come to that section. That was the vision that came to me in the midst of my ministry in the South, and we endeavored to hitch up the First Church of Atlanta to the great problem of the South.”

However, southern racism proved impervious, and its intransigence ensured that Proctor’s emergent social gospel ministry would continue to be decisively shaped by Atlanta’s increasing racial proscriptions and restrictions. Thus, First Congregational’s lauded employment bureau, library, schools, resident home for Black women, recreational facilities, its public water fountains, and even annual music festival were all occasioned in large measure by Jim Crow policies that severely restricted or barred essential services and accommodations to the city’s Black residents.

The realities of race and resurgent racism decisively influenced the focus and scope, as well as the style, of Proctor’s emergent social gospel ministry.

Belief in the efficacy of interracial cooperation was a core component of his theology, and it became a defining characteristic of his version of the social gospel, and of his institutional ministry. “The spirit of cooperation… between white and Black,” he recalled, “was perhaps the chief contribution that First Church of Atlanta made to social betterment during the quarter of a century of my pastorate.”

Proctor’s skill at engendering racial cooperation was also essential to his efforts at maintaining adequate support for the church’s burgeoning ministries. Ironically, his skill and success at forging cooperative and supportive alliances with influential whites, as well as his friendship with Booker T. Washington, left him vulnerable to charges by Black critics that he accommodated racial paternalism and was an “Uncle Tom.”

Proctor vigorously denied these charges, while noting that he was a “race man” and that his ministry of racial cooperation emphasized racial pride and active protest against racism. Amid increasing conflict between advocates of Washington and supporters of Du Bois, Proctor described his racial ideology as situated between the two, and called for “a broadness of spirit by which the radical and conservative elements may work together unitedly for the advancement of the race as a whole.”

“The Colored Doughboy” and the Great Migration

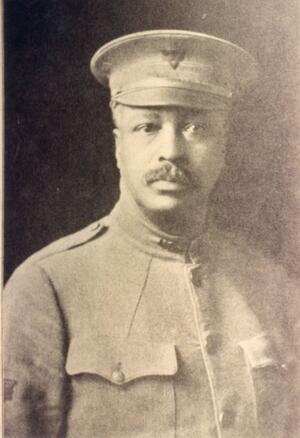

During the waning months of World War I, Proctor’s emphasis upon interracial cooperation and tolerance as integral components of his social gospel ministry attracted the attention of the United States military, which was being confronted with increasing unrest among Black soldiers. Upon invitation from the War Department and General John H. Pershing, Proctor was commissioned a military chaplain and sailed for Europe in early 1919.

However, Proctor would do more than placate and offer racial bromides to the more than a “hundred thousand” Black soldiers to whom he preached his message of applied Christianity. He protested the discrimination and abuse to which the Black soldiers were subjected and observed that they were brave but “dejected men” who “had come overseas to fight for that democracy for others” that they had never enjoyed at home.

However, Proctor would do more than placate and offer racial bromides to the more than a “hundred thousand” Black soldiers to whom he preached his message of applied Christianity. He protested the discrimination and abuse to which the Black soldiers were subjected and observed that they were brave but “dejected men” who “had come overseas to fight for that democracy for others” that they had never enjoyed at home.

Acutely sensitive to the broader impulse and currents of the era, Proctor also perceived that the war and its aftermath would have profound consequences for the returning soldiers and their communities and churches. Of crucial significance, he predicted, was the impulse “toward larger liberty,” as well as the participation of returning Black soldiers in what he called the “national redistribution” of the race occasioned by northern immigration. Thus, of related concern was the steady stream of former soldiers and Black migrants from the South into the urban and industrial centers of the North and Midwest and the myriad challenges that this massive population shift presented to the Black church and ministry.

From Atlanta to Brooklyn

As the twentieth century approached the troubled close of its second decade amid the ravages of war, the flu pandemic, and increasing racial strife, Proctor reflected on his twenty-five-year ministry at First Congregational. The congregation had grown “from 100 to more than 1,000” and by most accounts, his efforts to foster a social gospel ministry and institutional church in the heart of the urban South had been eminently successful.

Nevertheless, he remained acutely aware of the limitations of his success in Atlanta, and most notably that the South’s “peculiar problem” had not yielded in any appreciable extent to his ministry of social activism and racial cooperation. Continued racial restrictions imposed on Atlanta’s swelling Black population heightened the demands upon his overextended ministry, and Proctor often found himself apologizing to his parishioners because the constant necessity of raising funds for the church’s institutional ministry distracted from his pastoral responsibilities.

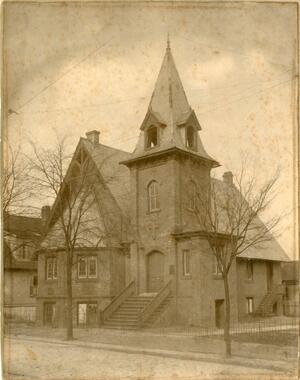

A call to Brooklyn’s Nazarene Congregational Church to replace Albert P. Miller 1885 B.D. provided Proctor an opportunity to apply his version of the social gospel amid the complexities and challenges of northern urban life. In 1919, he ended his twenty-five-year ministry “in the heart of the South” and accepted the call to Nazarene Congregational Church which had been found in Brooklyn, New York with the assistance of Solomon Coles ’74 B.D., second Black graduate of Yale Divinity School.

Proctor’s decision to break “the sacred ties of a lifetime” and depart Atlanta for Brooklyn was part of a bold and strategic plan to join the race’s migratory movement and extend his vision and model of a socially engaged church and ministry throughout the nation. Similar concerns regarding the “Great Migration” and its implications for the Black church and community were being voiced by Black leaders such as George Edmund Haynes, Richard Wright, Jr, W.E.B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson as well as Mary McLeod Bethune, and Nannie Helen Burroughs. All shared Proctor’s conviction that the traditional model of the Black church and its ministry was inadequate to meet the myriad challenges faced by the new urban migrants, and all agreed that there was a pressing need for a church and ministry specifically attuned to these challenges.

It was an analysis and prescription given added urgency by the spasms of racial violence that convulsed several northern and mid-western cities during the “Red Summer” of 1919. Proctor, whose institutional church and ministry in Atlanta had risen from the ashes of one of the nation’s worse racial conflagrations, was convinced that his efforts in Atlanta could serve as the model of a ministry and church that could successfully address these needs.

On January 1, 1920, Proctor departed Atlanta after delivering an emotional resignation sermon based on Acts 21:14 (“The Will of the Lord be done”), which explained to his dejected parishioners that his decision was inspired by a new vision that called him to “greater usefulness:” Honored with the title “pastor emeritus,” so that he should “always be officially connected with the church,” he was also granted the privilege of choosing his successor. His selection was Revered Russell Brown, whom he described as having “the social vision” and being prepared to “carry on the work … already begun in Atlanta.”

A year into his new pastorate, Proctor publicly elaborated on his reasons for relocating to Brooklyn. Figuring prominently in his explanation was the “gradual shifting [of the race] northward and westward … accelerated by national and international social and economic conditions.” Consequently, he explained, there had emerged “an entirely new set of problems” involving racial relations, health, education, politics, economic factors, employment, and business, whose solution was to be found in a church and ministry adapted to “the conditions of the hour.” Failure to adequately adapt, he warned, imperiled not only the well-being of the race but ultimately the church’s very existence.

A year into his new pastorate, Proctor publicly elaborated on his reasons for relocating to Brooklyn. Figuring prominently in his explanation was the “gradual shifting [of the race] northward and westward … accelerated by national and international social and economic conditions.” Consequently, he explained, there had emerged “an entirely new set of problems” involving racial relations, health, education, politics, economic factors, employment, and business, whose solution was to be found in a church and ministry adapted to “the conditions of the hour.” Failure to adequately adapt, he warned, imperiled not only the well-being of the race but ultimately the church’s very existence.

“The church of today,” he insisted, “must not only hold services; it must also render service. This is particularly true of the church that is going to shape and mold the colored people now drifting northward.” His vision of Nazarene as the centerpiece of an even more ambitious and expansive ministry was also shared: ”New York City is the center of the life of the American people. As goes New York, so goes the nation politically, commercially, socially, and religiously. This is, therefore, the place to build the first unit of a chain of churches across the continent that will function in the entire life of the Negro people… What the First Church of Atlanta meant to the people of the Gate City and the South we would make the Nazarene Church Community Center mean to the metropolis and the nation.”

As he set about this ambitious task, Proctor was fortunate to have the continued assistance of both his wife and Dr. Jesse Moorland. An 1891 graduate of Howard University’s Theological Department, Moorland shared Proctor’s commitment to applied Christianity. Having pastored churches in Nashville and Cleveland and served an extended tenure as Secretary of the Colored YMCA (1891-93; 1898-1923), he became Chairman of Nazarene’s Board of Trustees and functioned as Proctor’s right arm in the extension of Nazarene’s social gospel ministry.

At Nazarene, Proctor continued key components of his Atlanta ministry. Brooklyn, however, offered additional opportunities for its expansion. This was especially apparent within the realm of politics.

Like Washington Gladden, Proctor viewed political activism as compatible with a socially engaged and responsible ministry, and no longer hampered by Georgia’s racial restrictions, he became much more politically active. Similarly, interracial and ecumenical cooperation, which had evolved as a key component of his prophetic ministry in Atlanta, also became even more pronounced as the centerpiece of his Brooklyn ministry. He was supported and joined in numerous interracial and ecumenical efforts by Brooklyn Rabbi Alexander J. Lyons and especially by Dr. Samuel Parkes Cadman, prominent pastor of Central Congregational Church and President of the Federal Council of Churches from 1924 to 1928.

Moreover, Proctor’s optimistic message of interracial cooperation and racial reconciliation, emphasized in his 1925 autobiography titled Between Black and White, found special favor with progressive and moderate white clergy who hailed him as the “Henry Ward Beecher of the Colored Race” and “the best-informed man of his race on inter-racial relations.” Ironically, this emphasis and accompanying accolades would also leave Proctor painfully vulnerable to the criticism of more militant black ministers and leaders who would challenge his racial allegiance.

Growth, conflict, and crisis in Brooklyn:

By mid-decade, Proctor had become one of the leading clerics in the New York area, Nazarene had grown into the “largest Negro Congregational Church in the United States,” and local papers frequently carried favorable reports of his expanding ministry, as well as his timely social, political, racial, and even theological commentary. Among the latter were accounts of Proctor’s declaration, amid the raging modernist/ fundamentalist conflict that not only he but also “Jesus was a Modernist.” Also prominently featured in the local media was his proclamation, amid the related controversy accompanying the Scopes Trial, that he was “an evolutionist” and that “it is evident that evolution is God’s method of creation.”

Nevertheless, with his election in 1926 as the first Black moderator of the New York City Congregational Church Association (representing sixty-nine churches and a total membership of 31, 000), Proctor was positioned to pursue his dream of acquiring a “larger structure” with “institutional features” to facilitate his “enlarged work” and prophetic social gospel vision attuned to the modern era.

In his autobiography, he had described the changed conditions and challenges facing the Christian community and concluded “Evidently, we are on the borderland of a new world, not only in the application of modern science to the progress of mankind from a physical viewpoint but also in the application of the things of the spirit to the social relationships of man. Old things are passing away; all things are being made new.”

Especially concerned about the impact of these changed conditions upon the Black community, Proctor reiterated his call for the establishment of “a new type” of Black church and ministry—a church and ministry that was prepared and willing to be innovative in its application of Christianity to meet the changing needs of the Black community as it was confronted with the myriad challenges associated with increased mobility, urbanization, industrialization, secularization, as well as the era’s new scientific, intellectual, academic, and racial currents.

As in Atlanta almost twenty years earlier, Proctor successfully orchestrated a campaign in which pulpit and press were enlisted to present his new venture as critical not only to the welfare of the race and wider Brooklyn but also the nation. Illustrative was an article in the Brooklyn Eagle that readily exploited themes of piety and patriotism as it prominently featured a World War I era portrait of Proctor in chaplain uniform under the caption “For God and America” and explained, “How the Nazarene Congregational Church of Brooklyn Is Taking The Lead To Increase the Church Membership Of The 75,000 Colored People In This Boro By Planning A Greater Church.” It was a compelling appeal, and Proctor quickly garnered sufficient funds to secure the property of Brooklyn’s Church of Our Father, Universalist. Advantageously located on Grand Avenue near a growing black neighborhood, the property consisting of a church building with a seating capacity of 1,000, a community house with Sunday school rooms, ladies parlor, kitchen and dining room, and parsonage, became the impressive new home of Nazarene and its social gospel ministry.

With the purchase of a new edifice, Proctor appeared to be on the verge of replicating his success in Atlanta and realizing his vision of making Nazarene not only the leading Black church in Brooklyn but also the prototype of a nationwide string of Black institutional churches. However, the apparent success of his ministry in Brooklyn proved fleeting.

A bitter and destructive controversy evolved which embroiled much of Brooklyn’s Black ministry and ecclesiastical establishment. It was rooted in a complex convergence of intra-racial and ideological tensions; theological and hermeneutical concerns; ministerial styles and agenda; sectional and sectarian rivalry; clerical jealousy; and changing immigration patterns. Also graphically illuminated were liabilities inherent to the application of Proctor’s unique version of the social gospel within a rapidly changing and increasingly complex northern urban milieu amid an impending economic depression that made securing and maintaining funds necessary to meet the demands of an expanded institutional and social gospel ministry increasingly precarious.

In the aftermath of the painful and embarrassing controversy, Proctor found himself pastoring a shrinking congregation and attempting to maintain an attenuated social gospel ministry with severely reduced status and resources.

Seeking to recover his status and support, Proctor began a high-profile investigative series on Black immigration for the New York Herald that provided an opportunity for him to revisit his southern roots and engage in a more focused analysis of the causes and results of “Negro Migration from the South.” His observations and analysis illuminated his continued commitment to the social gospel and applied Christianity. Amid his travels throughout the South, he claimed to find evidence of a rural social gospel since some rural Black churches had begun to replace “the type of religious life suggested by ‘The Green Pastures’ ” with “a more practical type of church life… .[focused on] better housing, better schooling, better farming, and better citizenship.”

His concluding article published in 1931 reiterated his belief that despite its liabilities, the migratory movement had “given a mighty impetus to the colored church in the North” and fostered the development of “a growing group of level-headed, broad-minded ministers” who “are worthy leaders … endeavor[ing] to correlate religious education, spiritual culture, and social service.” Cited as examples were the ministries of Lacey Kirk Williams at Chicago’s Olivet Baptist Church; William De Berry at St. John’s Church in Springfield, Massachusetts; Charles A. Tindley at Tindley Temple Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia; and his own at Nazarene.

Proctor’s continued commitment to a version of the social gospel adapted to the peculiar needs of the Black church and community was also illuminated by his participation in a pioneering seminar on the Black church held in New Haven in the spring of 1931. There he joined prominent Black leaders and clergy, including Dr. George Edmond Haynes, A. Philip Randolph, and Benjamin E. Mays in a three-day seminar which was held at Yale Divinity School and organized by Black seminarians.

The seminar’s theme was “Whither the Negro Church?” and discussions focused on five topics of critical concern to Proctor and other Black proponents of the Black social gospel: “The Negro Church in a Changing Social Order;” “The Negro Church and Economic Relations;” “The Negro Church and Education;” “The Negro Church and Race;” and “Future Leadership of the Negro Church.” As summarized by an anonymous participant, the seminar’s operative theology and thesis was that “individual salvation can only be ensured through salvation of society.”

In answer to the question, “Whither the Negro Church?” seminar participants called for the Black church to “set itself to the task of developing a more prophetic and fearless technique in making applicable the implications of the religion of Jesus in relation to the social order,” and to “discover and develop a type of leadership that would do for America and the Negro race what Gandhi has done for India and what Jesus has done for the world.”

The seminar and its participants both anticipated and encouraged the model of a Black church and ministry that would provide inspiration and resources for the emergent civil rights movement. Significantly, a number of the seminar participants, most notably A. Phillip Randolph and Benjamin Mays, would play prominent leadership roles in the emergent movement which would be identified in large measure with the social gospel theology and ministry of Martin Luther King.

Proctor, however, would not be afforded a direct role in the emergent movement. He died unexpectedly on May 11, 1933.

Ironically, Black Brooklyn, including many of his clerical adversaries and critics, turned out en masse to offer belated tribute at his funeral. Among clergy officiating was his close friend, fellow social gospel activist, and confidant, Samuel Parkes Cadman.

Alluding to the bitter controversy that had marred Proctor’s final years, Cadman proclaimed prophetically that his life and pioneering ministry were the “wave offering of a rich and endless harvest.” Amid the additional posthumous tributes paid Proctor was a resolution passed by the national boards of the Congregational and Christian Church that acknowledged him as ”a pioneer in the modern movements of inter-racial goodwill, a loyal Congregationalist, and a gentleman of rare dignity and poise …”

Alluding to the bitter controversy that had marred Proctor’s final years, Cadman proclaimed prophetically that his life and pioneering ministry were the “wave offering of a rich and endless harvest.” Amid the additional posthumous tributes paid Proctor was a resolution passed by the national boards of the Congregational and Christian Church that acknowledged him as ”a pioneer in the modern movements of inter-racial goodwill, a loyal Congregationalist, and a gentleman of rare dignity and poise …”

One of the most poignant of Proctor’s tributes was penned by W.E.B. Du Bois. Recalling their meeting as students at Fisk, Du Bois acknowledged Proctor’s unwavering faith and the prophetic theology and ministry that it nurtured:

One of the first men I met, when I came to Fisk in 1887 was Henry Hugh Proctor, a long lanky youth… he grew into a strong and forceful man and dying before his day, left a mark on the world. He was an evangelical Christian so honestly orthodox that any question of fundamental truth never entered his mind. So sure to him was its foundation that he could play with it, compromise for it, adapt it to circumstances, perfectly and eternally certain of ultimate rights. To the skeptic, therefore, the natural questioner and heretic, Proctor was anathema. But to the doer of the Word, he was a strong Tower. He spared neither his strength nor money in his life work and was supremely indifferent to mere matters of income and expense…

With the precision of a social scientist, Du Bois also offered an insightful analysis and explanation of the success of Proctor’s ministry in Atlanta and its failure in Brooklyn:

His great work was the community church in Atlanta, perhaps the first and certainly one of the most successful in Colored America. He put in a life work there and then essayed a larger field in Brooklyn. But neither the time of his coming nor the character of this community was suited to his plans. Old Brooklyn is ever cold to the stranger and suspicious. Yet he was ever at the edge of a new triumph … but he fell victim of the Depression before his new effort was thoroughly established…

Fittingly, Proctor’s body was returned for burial to the site of his earliest and most successful social gospel ministry. After a memorial service at First Congregational Church, his remains were interred in Atlanta’s Southview Cemetery.

Fittingly, Proctor’s body was returned for burial to the site of his earliest and most successful social gospel ministry. After a memorial service at First Congregational Church, his remains were interred in Atlanta’s Southview Cemetery.

Epilogue

Ironically, a year after the death of Proctor, Nazarene Church, once described as the most impressive Black church in Brooklyn and the envy of many of its ecclesiastical neighbors, was sold at public auction as a result of foreclosure proceedings.

Jesse Moorland, serving as Nazarene’s interim pastor, penned a poignant account of the congregation’s final departure from the edifice—adding that Nazarene had relocated its offices and smaller services to a “store building” at 1714 Fulton Street, while its larger Sunday services were held at the Carlton Avenue Branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association.

Moorland also announced that Nazarene had called a new pastor, the Rev. Shelby Rooks, who “is well-liked by the people, and has great promise.” Rooks, a recent graduate of Union Theological Seminary, had been strongly endorsed by Charles Emerson Fosdick and would be assisted during a portion of his five-year ministry at Nazarene by another Union graduate and proponent of applied Christianity—James H. Robinson.

Notwithstanding their efforts and those of the succession of ministers and interns who followed them, Nazarene survived as a mere shadow of the exemplar of the social gospel envisioned by Proctor upon his migration from Atlanta to Brooklyn. However, Proctor’s social gospel legacy continued to be represented at Atlanta’s First Congregational Church. Homer C. McEwen, who served as its senior minister from 1947 until 1979, observed that more than half a century after Proctor’s departure for Brooklyn, First Congregational continued “to pioneer in the areas of social usefulness which marked it in the days of Henry Hugh Proctor. Indeed this is part of the rich heritage which his generation bequeathed to the church.”

This “rich heritage” of “social usefulness” was reflected in the support that First Congregational’s clergy and congregation provided for the social gospel and civil rights activism of Martin Luther King, Jr. Not incidentally, King, the maternal grandson of Proctor’s ministerial colleague Adam Daniel (“AD”) Williams at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Church, was born and raised in the elongated shadow cast by First Congregational.

First Congregational would also help to nurture the ministerial and political activism of a King associate and confidant—former Atlanta mayor, former congressman, and former United Nation’s ambassador —Andrew Young, who presently serves as an associate minister at First Congregational Church. A more direct linkage to both Proctor’s heritage and Yale Divinity School is illuminated by the socially, politically, and culturally engaged ministry of the church’s longtime senior pastor and YDS graduate Dwight Andrews ’77 M.Div.

First Congregational would also help to nurture the ministerial and political activism of a King associate and confidant—former Atlanta mayor, former congressman, and former United Nation’s ambassador —Andrew Young, who presently serves as an associate minister at First Congregational Church. A more direct linkage to both Proctor’s heritage and Yale Divinity School is illuminated by the socially, politically, and culturally engaged ministry of the church’s longtime senior pastor and YDS graduate Dwight Andrews ’77 M.Div.

Within the academy, the importance of Proctor’s contribution to the history and historiography of the social gospel movement is being belatedly acknowledged by a new generation of scholars of American and African American history, theology, and ethics. And, as predicted by Cadman at his funeral, Proctor’s ministerial legacy of “a rich and endless harvest” is bearing fruit among a new generation of clergymen and women and is most prominently represented by the activist, interracial, and international ministry of “applied Christianity” preached and practiced by the Rev. Dr. William Barber, founder of “Repairers of the Breach” and visiting professor of Public Theology and Activism at Union Theological Seminary.

Dr. Moses Moore ’77 M.Div. is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Arizona State University.