By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

After a year filled with devastating losses, many Americans are struggling with grief. While grief is difficult for everyone, it can be especially challenging for children. This is why organizations like Good Grief are so critical. Run by Joseph Primo ’06 M.Div., Good Grief helps kids and their families build coping skills and resiliency around death.

The foundational experience that led Primo to this work occurred when he was just fourteen years old.

“My kid sister and I were staying with my grandparents,” he said. “My aunt came over for lunch one day, and we were eating tuna melts and salads when her head just dropped and she let out the death groan—the oxygen went straight out of her.”

“My kid sister and I were staying with my grandparents,” he said. “My aunt came over for lunch one day, and we were eating tuna melts and salads when her head just dropped and she let out the death groan—the oxygen went straight out of her.”

Primo looked on helplessly while his grandmother, a trained nurse, tried to revive her.

“We were in rural Maine with volunteer paramedics, so it took them thirty minutes to arrive,” said Primo. “I just grabbed my grandmother’s rosary beads and started praying my heart out. My eleven-year-old sister looked panicked, so I locked her in the closet. I didn’t want her to see anything. Unfortunately, I thought I needed to protect her.”

Primo recalls distinct sense memories from that afternoon: the beeping sounds of a defibrillator, his grandfather’s struggle to tie his shoes, the smell of urine left by his aunt.

After his aunt was officially pronounced dead, the family sat together in shock and grief. Then Primo’s grandfather had an idea.

“My grandfather turned on the organ, and boy, could that man could play,” Primo said. “The environment changes when something traumatic like that happens, but his music was healing. It helped clear the air, so to speak.”

A challenging aftermath

Witnessing the death of his aunt was very difficult for Primo, and he found himself struggling to process it.

“My family let me talk about it for the first couple of weeks, but then they didn’t want to hear about it anymore,” he said. “Too often adults have few resources around grief themselves. We need to move through grief, not around it. Without any guidance, my body started reacting, and I developed serious digestive issues.”

Additionally, Primo began struggling in school. One incident in his typing class was especially revealing.

Additionally, Primo began struggling in school. One incident in his typing class was especially revealing.

“I kept retyping the story of what happened,” he said. “The teacher told me to stop and sent me to the counselor, who gave me nothing of value. Ultimately, I had to discover my own resilience. If I’d had a supportive environment, resilience would have risen naturally; instead, I had to dive for it alone.”

Primo did find some healing in the footsteps of his grandfather: through music. He started to play the piano at his church. (His attraction to the keyboard would follow him to YDS, where he played piano for the weekly gathering of the Catholic student group.)

“Music became a source of strength,” he said. “It helped fulfill me.”

In college, Primo felt called to address social injustices and decided to go to divinity school. Part of the attraction of YDS was the supervised ministry requirement. When he learned that Connecticut Hospice was nearby, it felt like a natural fit.

“I was exposed to young people losing parents and parents losing children,” he said. “The experience was eye-opening, and I was not equipped.”

While doing this work, Primo began to study end-of-life ethics.

“I studied with Margaret Farley, a YDS professor who is an amazing medical ethicist,” he said. “I researched and wrote about end-of-life care.”

After his supervised ministry at Connecticut Hospice, Primo continued to work there as a chaplain for several years.

“Everything I experienced at the hospice planted a seed in me, and that seed was ultimately watered when I began working for Good Grief.”

Empowering children

Started three years after 9/11, Good Grief is a New Jersey-based organization that facilitates healthy coping and resiliency in the lives of children who’ve lost loved ones. In addition to their family support centers and advocacy work, the organization helps educators teach resilience through their Good Grief Schools program.

“In 2007, I moved to New Jersey and became the center’s director,” Primo said. “I took all my experience and research and helped create a nurturing environment for ongoing sharing and remembering. We need to increase children’s emotional and spiritual intelligence around this universal human experience.”

Instead of one-on-one therapy, Good Grief uses peer support, bringing grieving people together to form a caring community.

The staff at Good Grief emphasize that grief is not a solitary act, and death is not an isolated event.

“You lose your person and before you know it, your grandparents no longer visit because you remind them of their kid, or your house has to be liquidated, or friends don’t call because they feel awkward,” Primo said. “We help kids navigate those changes.”

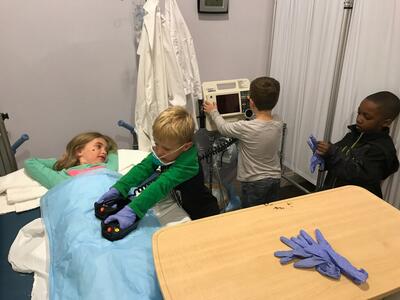

One way they do that is through Nights of Support, which start with a pizza dinner before families break into groups and do age-appropriate activities. These Nights of Support can be seen in the newly released MTV documentary, “Beautiful Something Left Behind.” The award-winning documentary follows children at Good Grief as they try to make sense of their loss.

Patty Ryan understands how grief can affect children. She had a 16-year-old daughter and 14-year-old twins when her husband died on 9/11.

“I was in a support group for surviving spouses and parents, but for the children, there was nothing organized, nothing that normalized grief for them,” she said. “It’s traumatic for a child. It’s very hard to connect with other kids when you lose a parent so young.”

Years after her own devastating loss, Ryan heard about Primo’s work and reached out. She met Primo for lunch and took a tour of Good Grief, located in Morristown, N.J.

Other Good Grief rooms include a theater room, a music room, and an arts and crafts room.

“This is better than traditional therapy because kids—and many adults—are missing the language around death and grief,” she said. “This community helps kids play with other kids and share their experiences.”

Ryan was so impressed that she decided to start a Good Grief in Princeton, N.J., recreating the same environment. Although she has worn many hats, her hardest and most rewarding position has been as family coordinator.

“You are the first contact with the families who need your services,” she said. “It’s so rewarding when the kids come to the center and their faces light up when they see the magical rooms. The teens don’t want to be there, but they tend to soften as we take the tour. These families arrive so broken, but they make friends and, within a few months, they heal in front of your eyes.”

Although Good Grief was not around for Ryan and her children after their loss, it still gives her great comfort.

“I’m happy to have found it,” she said. “I needed it in my life.”

It was very difficult for Lota to lose her father while in middle school.

“He was totally my normal,” she said. “He’d take me to dance and archery and fishing. I went from seeing him everyday to him being completely gone. Grief is hard enough at any age, but when you go through it as a child, your whole life turns inside out, and you don’t know how to cope.”

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation,a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.