By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

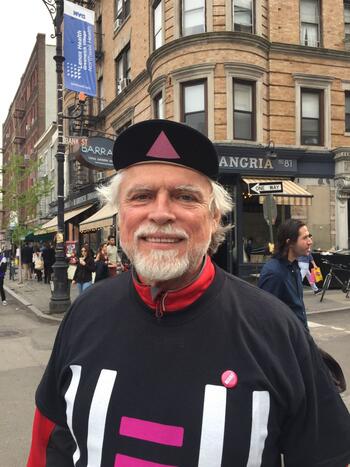

On December 2—World AIDS Day—longtime activist Charles King ’83 M.Div., ’89 J.D. visited his divinity alma mater to deliver a special sermon in Marquand Chapel titled “The Curse of Stigma.” He was struck by how much the campus culture had changed in the decades since his graduation.

“I was finishing my studies at YDS when the AIDS epidemic began,” recalled Rev. King, the founder of Housing Works, an organization fighting to end the dual crises of AIDS and homelessness. “I was also working as a pastor at New Haven’s Immanuel Baptist Church. Many gay men from the church were dying, but no one talked about it. The shame was far worse than the disease.”

“I was finishing my studies at YDS when the AIDS epidemic began,” recalled Rev. King, the founder of Housing Works, an organization fighting to end the dual crises of AIDS and homelessness. “I was also working as a pastor at New Haven’s Immanuel Baptist Church. Many gay men from the church were dying, but no one talked about it. The shame was far worse than the disease.”

Currently, there are 40 million people living with HIV around the globe, and according to UNAIDS, 50 million who’ve died since the epidemic began. King believes many of these deaths could have been prevented if AIDS had not been dismissed as a “gay disease.”

“I was still closeted as a student at YDS and didn’t know anyone at the school who was out,” said King, who in 2016 received the Divinity School’s William Sloane Coffin Award for Peace and Justice. “There was a lot of shame. But when I delivered my December sermon, it was wonderful to see so many students openly living their truths.”

Childhood abuse

During King’s childhood on a small farm in southern Texas, his family struggled to make ends meet.

“I had nine siblings, and money was tight,” he said. “My brothers and I were often rented out to pick cotton.”

But the most challenging part of his childhood was his tumultuous relationship with his father, an evangelical Baptist minister.

“My father singled me out for abuse starting at a very young age,” he said. “I didn’t understand at the time, but it’s because he worried that I was gay and could not be saved. He tried to ‘beat the devil’ out of me.”

King’s father—a member of the ultraconservative John Birch Society—would also periodically “disown” him, separating him from the rest of the family and forcing him to eat and sleep alone.

King’s father—a member of the ultraconservative John Birch Society—would also periodically “disown” him, separating him from the rest of the family and forcing him to eat and sleep alone.

“The first time he disowned me was when I proclaimed that Christians couldn’t kill,” he said. “He asked what I’d do if Communists tried to murder us, and I said we’d go to heaven. He didn’t like that answer, so I was temporarily disowned. I was five years old.”

While King calls his mother a “genuinely kind woman,” she was submissive to his father and unable to help. King found solace in books and recalls being the favorite of the librarian.

“She’d always have some books saved just for me,” he laughed.

Upon reaching adulthood, King was the only one of his siblings to leave home. He attended a public university before spending a semester at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth. He also worked as a street minister at a church in San Antonio.

“I worked on issues of race and homelessness and ran a support group for young gay male sex workers,” he said, and then smiled warmly. “It was interesting and awakened the activist inside me.”

Yale Divinity and Yale Law

When King decided to leave Texas and finish his seminary degree at YDS, his father disapproved.

“He believed Yale was too progressive, so he lied to people about what I was doing,” King said. “This led me to finally come out to him, and he disowned me for the last time. I did not speak to him or the rest of my family until he died years later.”

Although cut off from family, King thrived at YDS and beyond. He was hired as a graduate fellow at Dwight Hall to work on social justice and took an influential course on the church and social change with feminist theologian Letty Russell.

“Instead of writing a paper, we chose an organizing activity relative to the church,” he said. “I organized a rally to protest Reagan’s Health and Human Services budget cuts and learned how to be hands-on.”

King also worked as a pastor at Immanuel Baptist Church for three years. As AIDS cases increased, however, King’s life—like so many others—would reach a turning point. He recalls the moment when everything changed.

“The church’s minister of music was dying of AIDS,” he said. “When I visited the hospital and offered him prayers, he said that God was punishing his homosexuality. We just hugged and cried. I said if that were the case, I would be in the next bed.”

King left the hospital that day committed to a life of advocacy.

“I figured I should learn the law,” he said. “I ended up at Yale Law, graduating in 1989.”

Battling AIDS and homelessness

While at YLS, King became involved in New York’s ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). As part of his activism, he attended a political protest in Louisiana and met some men without housing who were living with HIV. He brought them to New York for a better life but learned some harsh truths.

“At the time, services for New Yorkers living with HIV—including rental assistance, nutrition, and transportation allowance—were available for those with places to live,” he said. “But if you were homeless, you needed a clinical diagnosis of AIDS. Hospitals wouldn’t run the tests because they couldn’t discharge those who tested positive. It was a discriminatory, bureaucratic nightmare.”

“At the time, services for New Yorkers living with HIV—including rental assistance, nutrition, and transportation allowance—were available for those with places to live,” he said. “But if you were homeless, you needed a clinical diagnosis of AIDS. Hospitals wouldn’t run the tests because they couldn’t discharge those who tested positive. It was a discriminatory, bureaucratic nightmare.”

This nightmare led King to create Housing Works in 1991—an organization providing care, guidance, and homes for people with HIV who may also abuse drugs.

“There was not just stigma around HIV, but around drug and alcohol abuse,” he said. “Housing programs want people to prove their sobriety before moving in, but it’s hard to get sober if you’re on the streets and sick. It’s counterintuitive because proper housing dramatically reduces high-risk behavior.”

King’s light blue eyes brighten when he shares how Housing Works became the country’s first supportive housing for those living with HIV without regard to drug or alcohol abuse.

“We began with 40 available housing units and now have 4,000,” he said. “It’s heartening to see the fruits of our hard work. Of course, there’s always more to be done.”

Ending an epidemic

In 2014, King started a campaign to end the AIDS epidemic in New York State, successfully lobbying Governor Andrew Cuomo to get on board.

“Cuomo appointed me as co-chair of the task force, and by 2016, we got housing for any low-income person living with HIV in NYC,” King said. “Again, we are the first jurisdiction in the country to do this.”

Another milestone came in 2019, which saw the fewest AIDS diagnoses in New York since 1981.

“Despite opposition and cutbacks, the downward trend continues because of dedicated people,” he said.

One of those dedicated people is Jennifer Lester, director of Housing Works’ Readiness for Work program, who’s worked with King for 30 years.

“Charles is the most nonjudgmental person on the planet,” said Lester. “He has a deep sense of right and wrong and knows what the community needs. I’ve lost count of his arrests for civil disobedience.”

Ginny Shubert, cofounder of Housing Works, recalls one of her first experiences with King.

“Lots of people with AIDS were homeless because they didn’t have proper diagnoses and couldn’t enter shelters,” she said. “I sued the city about this, and Charles—who just graduated Yale Law—occupied the office of the commissioner of Human Resources Administration, handcuffing himself to his desk until they housed my plaintiff. There’s nothing he’s afraid of.”

Shubert has loved working with King all these years and speaks proudly of their extended work during Covid.

“The city sent people in shelters with Covid to packed emergency rooms when they only needed a place to recover,” she said. “Housing Works brought them into hotels. We said, ‘Just come inside; we’ll take care of you.’”

Hope in the dark

As the current political leadership dismantles humanitarian efforts and freezes funding for vital programs, King has grave concerns.

“There are thousands of people globally living with HIV and unable to get treatment,” he said. “It’s particularly critical for trans women—who have the highest risk for HIV—as well as gay and bisexual men, who have the second highest risk. It’s a complete disaster when it comes to ending AIDS as a global epidemic.”

But King is no quitter and warns against the crippling effects of fear.

But King is no quitter and warns against the crippling effects of fear.

“We must operate from a place of hope and act accordingly,” he said. “Congress authorizes the funding of USAID, so we should all contact our federal representatives and weigh in.”

King finds inspiration in the gospel song “If I Can Help Somebody.”

“The song goes, ‘If I can help somebody as I travel along, my living shall not be in vain,” he said. “I call it my theme song because the ability to transform lives—even just one person’s life—is so powerful. It’s a reminder that each of us can make a difference. Each of us has the power to fight stigma and transform lives.”

Lauren Yanks ’19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and the founder of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, www.bluebutterflyfoundation.org, a nonprofit organization that rescues and educates women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.