By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

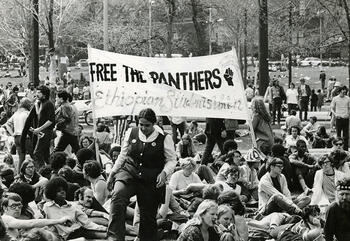

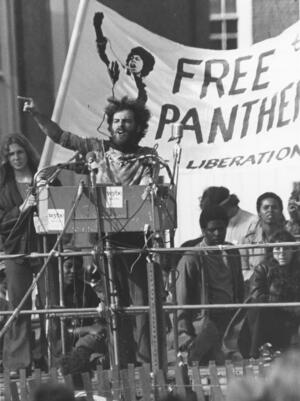

Fifty-one years after the historic May Day protest on the New Haven Green, YDS alumni of the era are reflecting on the momentous events of a half-century ago and how they shaped their lives.

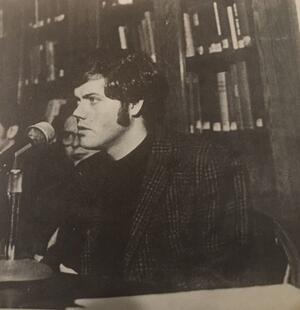

Leading the discussions—via Zoom gatherings and by other means—has been Philip Blackwell ’70 B.D. While Blackwell was more of an onlooker at the time, his observations planted seeds that have continued to blossom in his life and work.

“As a young man finishing my last semester at YDS, the protests on May 1, 1970, woke me up in so many important ways,” he said. “I watched tens of thousands of students and activists gather together to protest the arrest of Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins. Listening to the passionate speeches from so many activists, and the creative way Yale responded to the crisis, changed my life and taught me how to advocate for social justice.”

The events leading to the protest reveal a time of societal upheaval, suspicion, and turmoil. With questionable evidence, Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale and New Haven chapter leader Ericka Huggins had been charged with the murder of 19-year-old Alex Rackley, a fellow Panther suspected of being a police informant. The Panthers denounced the arrests, calling on supporters to come to New Haven on May Day and make their voices heard.

The events leading to the protest reveal a time of societal upheaval, suspicion, and turmoil. With questionable evidence, Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale and New Haven chapter leader Ericka Huggins had been charged with the murder of 19-year-old Alex Rackley, a fellow Panther suspected of being a police informant. The Panthers denounced the arrests, calling on supporters to come to New Haven on May Day and make their voices heard.“PANTHER AND BULLDOG”: Read more about the events of May 1, 1970

“New Haven became the epicenter for those who thought Seale and Huggins were wrongfully charged, but there were demonstrators of all kinds, including those who believed Yale lagged on civil rights issues,” said Blackwell. “There is a lot in this story to reflect upon.”

Blackwell stresses how much can be learned from May Day 1970 that speaks to our current challenges.

“It’s important to have this discussion, especially in the times we find ourselves,” he said. “We need to reflect on what was created and what can be built upon. Everyone should step out of their comfort zone and get involved. If I could do it, anyone can.”

A segregated childhood

A segregated childhoodBorn in Danville, Illinois, Blackwell grew up in what he refers to as “small-town, conventional life.”

“My mother was a housewife, and my father was a highly dependable manager of a paint store,” he said. “There wasn’t much diversity in our area. There were Black families living in Danville, but they were segregated to another part of town, and we never saw them.”

Blackwell went on to the University of Wisconsin, where he majored in English. After graduation, he decided to go to seminary.

“I was not driven by a divine call, but I thought I’d give seminary a try anyway,” he said. “I had no idea what I was getting into.”

On Blackwell’s first day at YDS, he walked into the Common Room and found a group of students kneeling together by the fireplace.

“I thought they were praying or meditating, but when I got closer, I saw they were playing pick-up sticks,” he said with a laugh. “So that was my introduction to seminary.”

Blackwell credits YDS with helping him learn how to read and think critically. “Overall, I really learned how to learn, and that’s stuck with me through my years of ministry,” he said.

Blackwell’s favorite class was called “Emotions, Passions, and Feelings.”

“The class was taught by the great Don Saliers, who went on to teach at Emory,” Blackwell said. “I’d never guess there would be a class on such topics. It looked at the role of emotion and feeling in Christian prayer and worship, as well as in human interaction.”

While Blackwell learned much in his studies, he learned even more outside of them, he says—especially when it came to civil rights issues. “The classroom instruction was formative, but communal experiences were transformative,” he said.

In fact, the first time Blackwell ever had a conversation with a Black person was at Yale. “Up until then, I basically lived a segregated life without consciously realizing it,” he said.

May Day memories

Blackwell recalls how, as March 1970 unfolded, it became clear that a major rally—with rumored violence—was on its way to New Haven. People began working behind the scenes to prevent any damage or bloodshed. This led to a lesson in cooperation and mediation: university administrators, faculty, and students from Yale began to meet with representatives from the Black Panther Party, the New Haven police department, and city leaders to discuss how to get through May Day weekend in a peaceful manner.

“Sam Chauncey was very involved with this issue and was the number one representative for (Kingman) Brewster, Yale’s president,” said Blackwell. (Chauncey, special assistant to Brewster for many years, joined Blackwell and fellow alumni from the era for one of their Zoom discussions.)

One critical decision made by the administration about May Day was to open Yale to demonstrators, offering food and a place to sleep.

One critical decision made by the administration about May Day was to open Yale to demonstrators, offering food and a place to sleep. “Instead of marginalizing protestors, they decided to feed them,” said Blackwell. “I really believe this saved the day. It was amazing to see such diverse people come together.”

On the day of the protests, Blackwell remembers spending seven hours on the Green, taking it all in.

“The main focus was on the Bobby Seale trial, but there were all sorts of movements represented,” he said. “There was the women’s movement, the farmworkers movement, the environmental movement, the antiwar movement, and more,” he said. “All of those movements had energies on the green. It was a festival of urgency.”

Although merely an observer, Blackwell would never be the same after that day.

“I remember looking directly into the eyes of the National Guard and thinking that our country had lost its way,” he said. “I also saw the urgency for the Black Panthers and realized that it was not a radical, anti-American movement, but a preservation movement and a call to the rest of us to get it together.”

‘Model for engaging community’

Another facilitator of the Zoom discussions has been David Warren ’70 M.Div., ’70 M.U.S. Warren’s life had already been steeped in civil rights before May Day. Having marched with Martin Luther King Jr. from Selma to Montgomery, he also spent a year in India with Gandhi’s remaining advisors, learning about nonviolent resistance. He enrolled at YDS in 1966 and cross-enrolled at the School of Art and Architecture. “I wanted to look at race and poverty and gentrification,” he said.

Warren chose to study at Yale because the renowned activist and preacher William Sloane Coffin ’56 B.D. was the University’s chaplain.

“I chose Yale because Bill Coffin was there,” he said. “He was deeply involved with the antiwar movement, the civil rights movement, voter registration, and was a close colleague of MLK. Bill was my mentor.”

At the time of the May Day events, Warren was the General Secretary of Dwight Hall at Yale, a service organization that helps students advocate for justice. He emphasized the key role Dwight Hall played during the lead-up to May Day.

“Dwight Hall was used to train nonviolent volunteers to stand between the National Guard and tens of thousands of demonstrators,” he said. “A group of peace activists helped us think it through. There were a number of YDS students who worked with me. It was a real hands-on experience.”

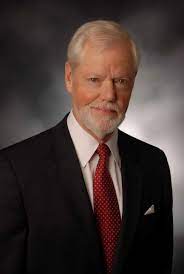

Warren would go on to become the Chief Administrative Officer of the City of New Haven and, after that, President of both Ohio Wesleyan University and the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities. He stresses the influence of May Day 1970 on society as a whole.

Warren would go on to become the Chief Administrative Officer of the City of New Haven and, after that, President of both Ohio Wesleyan University and the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities. He stresses the influence of May Day 1970 on society as a whole. “It was an incredibly significant time and helped set an agenda to address all of these issues,” he said. “Bringing women to Yale was an example of that, as well as improving the relationship between the University and New Haven. There is still a huge distance to go, but Yale was in the national spotlight and became a model for engaging your community and drawing in students and addressing their cares and concerns.”

Coffins’ marshals

Also participating in the May Day 50th anniversary conversations has been Greg Turner ’70 B.D., a retired United Church of Christ pastor.

“When the forces began to respond to Seale’s arrest, Bill Coffin put together a coalition, and I was a part of that,” Turner said. “We were called ‘Coffin’s Marshals’ and were trained to stand between the National Guard and protestors. We also helped to control all the rumors swirling around New Haven.”

During the protest, Turner remembers the soundtrack of the Black Panthers.

During the protest, Turner remembers the soundtrack of the Black Panthers.“They were going around telling these white kids to cool it because they were playing into the hands of what the Nixon administration wanted,” he said. “At one point, I had to go up to the Trinity Church tower to get a perspective on what was happening on the Green. Things became comical when my walkie-talkie didn’t work.”

At the time, Turner’s wife—Kathy Turner ’69 M.Div.—was a new graduate of YDS and was training as a chaplain at Yale New Haven Hospital.

“The hospital was geared up in emergency mode for potential catastrophe coming from the Green,” he said. “One kid tripped and needed some stitches, but there wasn’t much else.”

For Turner, as for many of the YDS alumni revisiting May 1970, the heady time remains alive today, compelling their enduring commitment to greater causes.

“This is important to look at because of our cultural situation right now,” he said. “I have one of Bill Coffin’s quotes hanging in my office that reads: ‘Socrates had it wrong; it is not the unexamined but finally the uncommitted life that is not worth living.’ I try to follow that.”

‘Like walking into a room where a fight has taken place’

One participant in the May Day look-back was not yet on campus in 1970. But the fateful events were still alive when Frederick (Jerry) Streets ’75 M.Div. arrived at YDS in 1972. He likens the atmosphere to “the feeling one gets when one walks into a room where a fight has just taken place.”

From 1992 to 2007, Streets was Yale’s Chaplain—the first African American to serve in that role. Currently, Streets is the senior pastor of the Dixwell Congregational Church in New Haven and is a licensed social worker.

From 1992 to 2007, Streets was Yale’s Chaplain—the first African American to serve in that role. Currently, Streets is the senior pastor of the Dixwell Congregational Church in New Haven and is a licensed social worker. “The tension in the air was significant,” he remembered. “It was centered around a few things. One was the extent to which the Bobby Seale trial raised the issue of racism and police conduct. Feelings about that still lingered.”

While Streets praises the leadership of Coffin and Brewster for the handling of May Day, he believes greater work was needed after the trial ended.

“The awareness and the sensitivity were still there, but there was also a sense by the community at large that they had to continue to live with the issues, while the University did not,” he said. “The University could move forward easily.”

Streets suggests that Yale was still seen by many as a gated community.

“While Yale was smart to be more hospitable during the period of the trial, it was still suffering from the perception on the part of many, and experience on the part of some, to be closed off from the wider community and not that interested in the broader welfare of New Haven,” he said.

Streets believes there is a lot to learn from the events of May Day, as well as from the years following it.

“What we can take from an incident like May Day is that the University is not immune to the wider experience of human beings, particularly when it comes to matters of injustice,” he said. “You cannot ignore injustice forever; it will eventually find its way to your doorstep. For instance, the issues we’re talking about now—the rise of Asian-American hate, George Floyd, police brutality—you can’t see these incidents as if they’re ‘out there.’ They will come to your door because life is so intertwined, and we’re so interconnected. This pandemic exemplifies how our lives are in everybody’s hands. Until we live more relationally, things will not improve.”

Work not finished

After May Day and those last formative months at YDS, Philip Blackwell stepped into his life as a Methodist minister. His first church was in a dairy farm area in Illinois. He and his wife, Sally, moved there with 50 boxes of books and a mattress.

“We didn’t have much, but we made do,” he said. “I was just excited to get to know my new community. One of the first things I noticed was its lack of diversity. There were no Black people in the county.”

Since some of the kids had never even been out of their town, Blackwell decided to take them on a field trip to Washington, D.C.

“While on the trip, we watched a movie that showed one of the first sensitive portrayals about Black people in the South,” he said. “About fifty years later, one of those kids found me and told me I had changed her life; she never forgot that trip or that movie. She said I opened the world to her.”

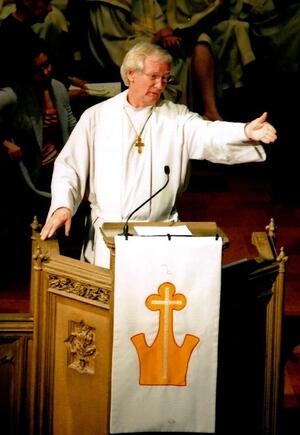

Blackwell would later move on to a church in the industrial city of Rockford, Illinois, and then became a campus minister at the University of Chicago. His final parish ministry was at the First United Methodist Church at the Chicago Temple. Among other programs, the church hosted a weekly lunch for those in need and started a multicultural theater program in the basement.

Blackwell would later move on to a church in the industrial city of Rockford, Illinois, and then became a campus minister at the University of Chicago. His final parish ministry was at the First United Methodist Church at the Chicago Temple. Among other programs, the church hosted a weekly lunch for those in need and started a multicultural theater program in the basement.Today, Blackwell mentors a cohort of 12 young clergy in Chicago, helping them claim the public dimensions of their ministry beyond their congregation walls.

“In this group are three Black people, a Latinx, a Korean, a rabbi, a Unitarian, a gay campus minister, and a socialist by her own proclamation, as well as a YDS graduate,” Blackwell said. “I feel right at home.”

Blackwell believes his life’s work truly started at YDS and the events surrounding May Day. At 77 years old, he is not close to being finished.

“There is still so much work to do,” he said. “My involvement in the May Day conversations is a culmination of all of my life’s experiences. May Day helped me to see things with much greater complexity. I see the demarcations of racial identity being invalid and irrelevant. I see why it’s important for me to stand outside a church every week and hold a Black Lives Matter sign. Some people yell cruel things out of their car windows, but it doesn’t matter. I now see that I hold up that sign not to change the world; instead, I hold it because the world has changed me.”

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.

April 27, 2021