By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

When he graduated from YDS and returned to his hometown in the Chicago area, Allen Reynolds ’15 M.Div. figured he would go into young adult ministry. So he has. Just not in the form he imagined.

Reynolds is the editor of UrbanFaith, a news and culture site geared to a young Black Christian audience. The site is published by Urban Ministries, Inc., where Reynolds has served for six years.

Reynolds is the editor of UrbanFaith, a news and culture site geared to a young Black Christian audience. The site is published by Urban Ministries, Inc., where Reynolds has served for six years.

“It’s really special to be able to reach thousands of people,” Reynolds said. “I’m passionate about youth Christian education and bringing together people from around the world.”

Diverse community

While growing up in the town of Flossmoor in the Chicago suburbs, Reynolds learned a lot about diversity.

“Flossmoor was a very rare community—especially at that time—where people of all races lived together,” he said. “It was instructive to see people experience racism and be empowered to navigate racial barriers. After various travels, I moved back to Flossmoor to raise my own family. There is still a lot of work to do, but we live then and now as one community.”

Reynolds shared some of his parents’ experiences while growing up in South Side Chicago.

“My father’s father was incarcerated, while my mom lost her own mother quite young,” he said. “As children, my mom had to become very responsible, and my father decided to become a doctor one day and help people.”

True to his vision, Reynolds’s father is an internist who continues to practice today. His mother worked as a math teacher but decided to become a stay-at-home mom when she had children.

“My mom’s decision to be a stay-at-home mom was not just great for me and my three siblings, it was great for so many others,” said Reynolds. “She was very involved in the community. She felt that if she wanted her kids to be leaders, she had to be willing to be a leader first.”

A challenging illness

When Reynolds was in the fourth grade, he began having bouts of “excruciating stomach pain.”

“I would feel so awful,” he said. “I’d lie on the bathroom floor and could not get up. My mom would feel helpless and lie on the floor with me.”

After removing his appendix and performing exploratory surgery, doctors diagnosed Reynolds with Crohn’s disease.

After removing his appendix and performing exploratory surgery, doctors diagnosed Reynolds with Crohn’s disease.

“Crohn’s disease is an autoimmune disorder that affects your digestive system,” he explained. “It causes inflammation to the digestive tract, and the pain can be debilitating.”

Throughout his childhood, Reynolds’s symptoms ranged from mild to severe.

“I’d feel OK for a while, and then there would be a flare-up,” he said. “When I was fifteen, I developed a growth on my digestive system and had another surgery.”

Experiencing illness at such a young age forced Reynolds to see the world differently.

“I came to appreciate life more,” he said. “When I was in the hospital, I saw many sick children. This led me to see life as a gift, as opposed to something I was owed.”

Reynolds’s health challenges also contributed to making him a “super motivated” student.

“I was a member of 27 clubs in high school and was vice-president of my class,” he said with a laugh. “My all-time favorite clubs were public speaking and acting.”

Additionally, Reynolds became very involved with church.

“I think my illness gave me a deep yearning for healing that helped strengthen my faith,” he said. “Also, I am only five-three, and that made me self-conscious. I felt that if God loved me, then I could love me, too.”

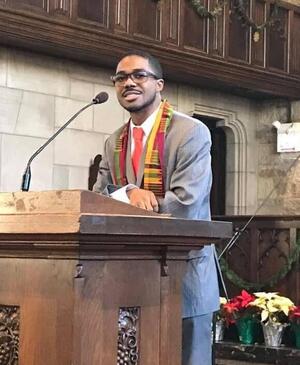

With his talent for public speaking, Reynolds preached his first sermon at fifteen. He describes the experience as “quite terrible.”

“I preached a sermon on a good tree bearing good fruit,” he said. “I said that if you see bad things in your life, then you do not have enough God in your life. Many kids in my youth group were struggling and thought I was being judgmental.”

While unable to understand their reaction at the time, Reynolds eventually was able to deepen his perspective.

“It was not until college—I attended Howard University—that I understood that God is not calling us to be perfect, and self-righteousness is not the way to salvation,” he said. “I learned greater humility as I matured.”

At Howard, Reynolds majored in radio, television, and film production, hoping to one day write Christian comedies.

“I wanted to make Christian TV,” he said. “I concentrated on writing scripts. I love the conception of stories.”

While enjoying college life, Reynolds’s began experiencing a flare-up from his illness. Again, he turned to his faith.

“I was part of a new church that was very charismatic and nondenominational,” he said. “They believed in prophecy, healing, and casting out demons. One day, amid all this prayer, I felt like I received something. I felt like I was healed.”

Reynolds walked out of that service painless for the first time in months. He shares how “there was this kind of knowing.”

“At the time of that service, I was on eight pills a day, including two steroids and six pills to regulate my digestive system,” he said. “After that service, I did not have any symptoms for five years. For me, it reinforced that culture of miracle, signs, and wonders.”

Reynolds was a big believer in this form of worship for a while, but it didn’t last.

Reynolds was a big believer in this form of worship for a while, but it didn’t last.

“Even though I was healed for five years, I would go on to see a dark side to that church culture,” he said. “For instance, it was frowned upon to go to psychological counseling. People were hurt by this. This is not what God has called for us. My dad is a doctor, and I believe that religion and science can coexist. There is room to go to your doctor and go to church and pray.”

The Jewish Jesus

Along with his spiritual ventures, Reynolds also broadened his thinking while at Howard. One professor, an Orthodox Jewish woman, made a deep impact.

“Her name was Molly Levine, and she taught a class on comparative religion on Christianity and Judaism,” he said. “I learned so much about how Judaism functioned in ancient times up until today.”

The class read books like From Jesus to Christ by religion scholar Paula Fredriksen. Reynolds loved the studies and received high marks in Levine’s class.

“Professor Levine told me I needed to get a formal theological education,” he said. “At first, I questioned it because people at that previous church said a theological education might hurt our faith. But something inside me lit up.”

Levine had attended Yale as an undergraduate and encouraged Reynolds to apply to YDS.

“I couldn’t imagine myself as Ivy League material, but Professor Levine helped me to imagine it, and I’ll be forever grateful for that,” Reynolds said.

Life at YDS

Reynolds entered Yale Divinity School in 2012.

“We were the biggest class of African Americans to ever enter YDS,” he said. “There were 26 of us. Then during my first semester, there was the unrest in Ferguson, and Black Lives Matters started. After coming from Howard, it was a very strange and chaotic experience to be in this elite New England institution.”

Naturally, Reynolds felt called to take on a leadership role.

“I was president of Yale Black Seminarians and started two initiatives, including a contemporary worship service and creating safe spaces where students could discuss race, sex, class, and other diversity,” he said. “I also joined YDS drama, which I loved.”

Reynolds says that he enjoyed every class he took at YDS and was especially drawn to Lamin Sanneh, a professor of missions and world Christianity who died several years after Reynolds’ graduation.

“He thought about things differently than most and was comfortable sharing diverse views on subjects like colonialism,” Reynolds said. “He challenged me to examine different perspectives.”

After graduating from YDS, Reynolds returned to Chicago.

“I originally thought I would become a young adult pastor, but it didn’t work out that way,” he said.

Instead, Reynolds began working for Urban Ministries, Inc. (UMI), the largest independent, African American-owned Christian media company. UMI publishes Christian education resources, including curriculum for Sunday School and Bible study. Reynolds started in the call center, but his natural talent and work ethic led him to quickly take on more responsibility.

A full life

Reynolds has worked for UMI for six years and is currently the editor of UrbanFaith.

“UrbanFaith has multiplatform content,” he said. “I run urbanfaith.com, which is daily commentary news for African-American young adults. It includes lifestyle, news, and cultural issues. Some of it is devotional.”

Reynolds loves his work and is involved in other projects, including working as the public speaking and acting coach in the local high school—the same high school he once attended.

Reynolds loves his work and is involved in other projects, including working as the public speaking and acting coach in the local high school—the same high school he once attended.

“I love spending time with students and teaching them to be better actors and speakers,” he said. “It’s as if my life has come full circle.”

Additionally, Reynolds is in the ordination process with the United Church of Christ.

“The ordination process has been tough with the pandemic, but it has been a wonderful opportunity for discernment and growth,” he said.

Married in 2019, Reynolds and his wife, Brittany, welcomed a baby girl in November 2020.

“My wife had two little girls when I married her, so now I am the father of three beautiful daughters,” he said. “It’s wonderful to be a ‘Girl Dad.’”

His wife agrees.

“Allen is an awesome father to all our girls and is such a generous, loving husband,” she said. “I first met him in 2014 and just got this feeling that I was supposed to know him. We weren’t flirting, we were both in other relationships, but we became friendly. Then we reconnected a couple of years ago and just started talking and never stopped.”

The Reverend James King is excited that Reynolds has stepped into marriage and fatherhood. He has known Reynolds since he was a child.

“I first came to Chicago as the youth pastor for New Faith Baptist Church,” King said. “Allen’s family attended the church and that’s how we connected.”

King says that Reynolds was a great kid and well-liked by his peers.

“He was very involved with the speech and drama club,” he said. “I went to many plays where he was the star. I remember he was the brown Peter Pan. Allen was always true to himself.”

King is also excited that Reynolds is working at UMI.

“UMI is distinctive,” he said. “If you’ve ever picked up a Sunday School book with a Black Jesus or Black people featured in the content, UMI is the first that started doing that and does it the best. A lot of people do not think of Christianity as a Black man’s religion, but when you see yourself in the stories and Scriptures, it says that God does understand and listens to me. God is in my neighborhood, too.”

The Reverend Julian DeShazier is currently the pastor of the University Church in Chicago and also met Reynolds as a boy.

“Even when he was young, Allen showed a love of God and had great wisdom in his words,” DeShazier said. “He is one of those people you hear speaking at sixteen with polish and confidence. It certainly came forth in his preaching.”

Reynolds was still at Howard when he did a summer internship at the church.

“Allen was my shadow,” DeShazier said. “He had big questions and wanted to spend time with someone who’d had similar questions. He was asking whether pulpit ministry was right for him and whether there was room for someone who likes debate and drama. I am someone who incorporates rap into my sermons, so I understood. Allen is now under our care for ordination. While he can certainly preach and do traditional ministry, he has all these other gifts as well. It’s a place where he can bring his holistic self.”

As Reynolds continues spreading his wide-ranging talents, his struggle with Crohn’s disease continues. For the past two years, he has gotten monthly infusions that help the healing process. His wife is inspired by his strength.

As Reynolds continues spreading his wide-ranging talents, his struggle with Crohn’s disease continues. For the past two years, he has gotten monthly infusions that help the healing process. His wife is inspired by his strength.

“I see Allen’s faith everywhere, but I feel it most in his journey with Crohn’s,” she said. “It’s moving to witness. Allen’s very wise, which is something I hear from everyone who knows him. He brings peace and security to our lives.”

Overall, Reynolds feels very blessed for all aspects of his life, including the wisdom gained from his illness.

“It’s all so rewarding,” he said. “Life has been so good to me and my family. God is taking care of us.”

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.