By Timothy Cahill ’16 M.A.R

Writing in 1992, Fr. Henri J.M. Nouwen recalled his first glimpse of Rembrandt’s masterpiece, The Return of the Prodigal Son.

The dramatic painting depicts the moment in the Biblical parable when the son returns home wretched and impoverished after squandering his inheritance. Unwashed and in rags, the prodigal kneels before his aged father, who, dressed in a sumptuous scarlet cloak, welcomes him with a compassionate embrace. In the surrounding darkness, a group of onlookers, including a resentful older brother, bears witness to the moment father and repentant son are reunited.

This is the image that captured Nouwen the first time he encountered it, as a reproduction on a colleague’s office door.

“I kept staring at the poster,” he later wrote, recounting the moment, “and finally stuttered, ‘It’s beautiful, more than beautiful. I can’t tell you what I feel as I look at it, but it touches me deeply.’”

Indeed, the encounter with Rembrandt’s painting helped set in motion a chain of revelations that reordered the final decade of Nouwen’s life. The image become so central to him that in 1992 he published The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Meditation on Fathers, Brothers, and Sons, a book that would forever link the Dutch Catholic priest to the painting, and by extension, the Gospel story’s spiritual force.

It was fitting, then, when earlier this year a new visual interpretation of the parable was unveiled at Yale Divinity School for the prayer chapel that bears Nouwen’s name. This Prodigal Son was commissioned as a new altarpiece for the Henry Nouwen Prayer Chapel, the octagonal stone sanctuary in the subterranean level of the Divinity Library. The artwork, which depicts Christ embracing the Prodigal Son, is a Byzantine-style icon painted by George Kordis, a modern master of Orthodox religious iconography based in Athens, Greece.

Kordis’ The Prodigal Son resonates with Nouwen’s deep affection for the Rembrandt, which he eventually travelled to Saint Petersburg, in the then-Soviet Union, to view in person. The icon augments the YDS visual landscape with a work steeped in the aesthetic and theological richness of Eastern Orthodox spirituality.

Triptych

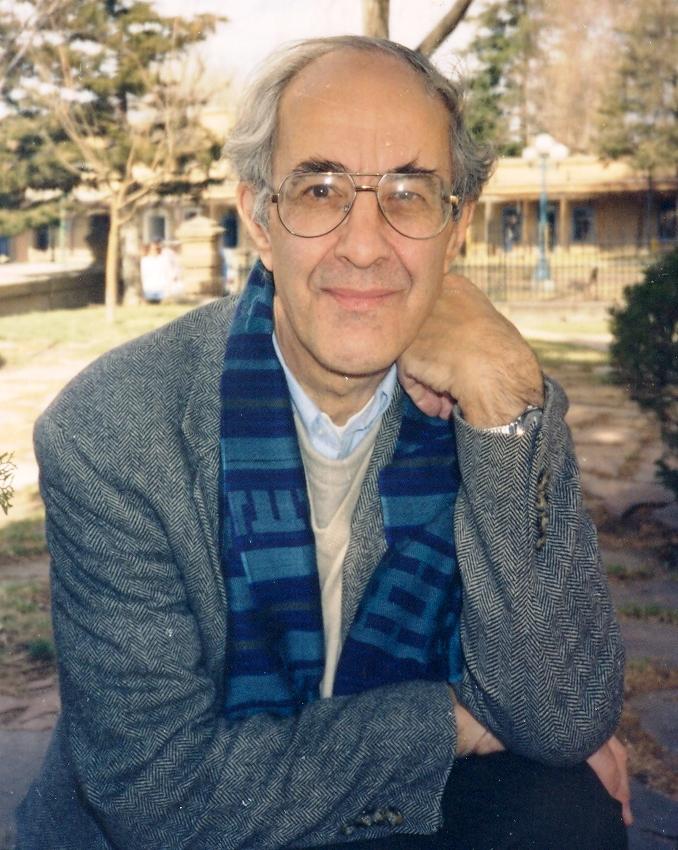

The new icon replaces a beloved triptych by Jesuit priest Fr. John Giuliani (1932-2021), commissioned for the chapel in 2007. When closed, the altarpiece shows the Tree of Life in bright turquoise and green; opened, its central panel depicts Christ in glory between heaven and earth, and is unique for its portrayal of Jesus as a Native American. The side panels assemble a dozen of Nouwen’s spiritual heroes, the eclectic convocation including Teresa of Avila, Mahatma Gandhi, Vincent van Gogh, Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, and Martin Luther King. Looking on in the lower right is Nouwen himself.

Among this gathering of canonized and secular saints is one figure, Canadian theologian and philanthropist Jean Vanier, who harbored a secret so poisonous that when it was revealed in 2020, it dismayed nearly all who had venerated his name. That year, L’Arche, the international network of residential communities for people with developmental disabilities that Vanier had founded in 1964, published an internal investigation finding him culpable of “manipulatively sexual relationships” with six women, nuns and assistants associated with the organization. Three years later, a more complete investigation concluded that between 1952 and 2019, Vanier had sexually coerced and abused 25 different women at L’Arche. None of his victims were part of the vulnerable resident population.

Vanier and L’Arche were pivotal to Nouwen’s spirituality for the last 13 years of his life. He was moved by the warmth of its residents and found pastoral fellowship among its caregivers—and its founder. In 1983, at Vanier’s invitation, Nouwen was a guest at a L’Arche commune in France when he had that first fateful glimpse of the Rembrandt painting. In 1986, Nouwen left a teaching position at Harvard Divinity School to become pastor at the L’Arche community in Toronto, where he lived and worked until his death a decade later, at age 64.

Nouwen spent 20 years as a professor of divinity in the Netherlands and U.S., but the school where he left the most enduring legacy was YDS, where he taught pastoral theology from 1971 to 1981. A scholarship is named in his honor, and at a 2018 conference examining the spiritual legacies of Nouwen and Thomas Merton, former Yale students of “Father Nouwen” spoke publicly of his lasting influence.

“What emerged from the succession of speakers,” I wrote at the time, reporting on the conference, “was the portrait of a man who celebrated daily Mass, hosted a weekly gathering with students over wine and theology in his apartment, and, as one former student put it, ‘spoke to my heart [in] a way no one had ever spoken to it.’”

It was such devotion that inspired alumni to raise the money needed to preserve the small prayer chapel and name it in honor of Nouwen. When the Sterling Divinity Quadrangle underwent extensive renovations a quarter-century ago, the lower level of Marquand Chapel, where the prayer sanctuary stood beneath its main altar, was annexed as an extension of the Divinity Library. Ever after, Nouwen Chapel has stood as a kind of secret retreat tucked away behind study carrels and rows of rolling bookstacks.

A difficult decision

When Fr. Giuliani created his altarpiece in 2007, Vanier was widely regarded as something of a living saint, and his inclusion in the painting, situated at the shoulder of the seated Nouwen, was obvious and fitting. The first revelations about Vanier emerged just before the Covid pandemic closed campus. When the subsequent investigation was released in 2023, just as life on the Quad was returning to normal, Dean Greg Sterling knew Vanier’s presence in Nouwen Chapel was untenable. (Nouwen himself is mentioned once in the nearly 900-page report, and no complicity in Vanier’s sexual misconduct is alleged or even hinted at by the investigators.)

Sterling brought the matter to the Yale Committee on Art in Public Spaces, the YDS faculty, and student groups. After extensive discussion and debate, a consensus emerged to remove the triptych.

“It was a very difficult decision,” Dean Sterling acknowledged. “It was a beautiful piece of art painted by a Connecticut Jesuit, and the only indigenous Jesus on the entire Yale campus. The figures on the side panels were people we all knew and admired, with that one glaring exception. And it was a gift funded by alumni who had deep affection for Nouwen.

“But what ultimately persuaded me,” he continued, “was talking with students who said—and I suspect that these were all survivors of sexual abuse—‘I simply cannot go into that space with that portrait of Vanier there. It's too painful.’ They didn't tell me they were survivors, but the tears in their eyes and the look of horror on their faces spoke volumes. That's all I needed to see. So, ultimately, I asked for the faculty to vote, and the vote was to remove it.”

Sterling immediately contacted the Henri Nouwen Society in Toronto and arranged to donate the triptych to the nonprofit organization, which maintains an archive and research collection dedicated to his legacy. The niche above the Nouwen Chapel altar was bare for more than a year until the YDS Walls Committee, following a proposal by committee member and Yale art historian Felicity Harley-McGowan, recommended the commissioning of an icon for the space. George Kordis was contacted on the recommendation of Vasileios Marinis, Professor of Christian Art and Architecture at YDS and the Institute of Sacred Music.

The Prodigal Son

The completed icon was unveiled in a ceremony at YDS this past January. In comments prepared for that event, Marinis described Kordis as “one of the most celebrated living artists in Greece.” (Marinis was unable to attend because of illness, leaving it to Harley-McGowan to deliver his remarks as well as her own.) The artist was born near the Aegean Sea in the hills of central Greece in 1956, and educated at the University of Athens, where he received his doctorate in theology and Byzantine aesthetics, and at the Holy Cross School of Theology in Brookline, Mass. He studied medieval art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and apprenticed with Cypriot master iconographer Fr. Symeon Symeou. He has held solo exhibitions throughout the world, and has produced both portable icons and monumental frescos across Greece and internationally, from Germany to Beirut, South Carolina to Melbourne, Australia.

Kordis is recognized as an important innovator in Greek icon painting. Well into the 20th-century, the highly stylized and symbolic art form was tied to, as Marinis noted, “a process of slavishly copying supposedly venerated prototypes” stretching back centuries. Kordis was the first to break with these restraints, freeing his use of line, color, and composition while remaining well within the tradition’s theological and aesthetic values.

His The Prodigal Son for the Nouwen Chapel is painted on an arched wooden panel nearly five feet in height and more than three feet across. The paint is egg tempera, an age-old medium of religious art in which powdered pigments are suspended in egg white. Lit by a pair of sconces and two round clerestory windows, the icon seems to hover above the chapel’s narrow altar. Entering the stone sanctuary, one is struck first by the bright glint of two gilt halos radiating from the painting. Their glow pierces the duns and grays of the room and contrasts with the otherwise subdued tones of the painting itself.

The icon, Marinis observed, exemplifies what is “personal, exciting, and deeply spiritual,” about Kordis’ work. “The two main figures, Christ and the Prodigal Son, are off-center, strangely elongated, and with large, expressive eyes. They are filled with light, in contrast to the left half of the icon, where Kordis depicts the despondent Prodigal Son almost in grisaille, standing in front of a fragmented architectural phantasy ... that communicates the sinner’s desperation. Above, several hills and the house of the Father are represented in a simple, almost childish style. The result is harmonious and delightful.”

Sustained attention yields the work’s complex visual language. The placid, consoling Christ is clothed in blue and rose robes, colors traditionally symbolic of Jesus’ dual nature, while the gold of the encircling halo is offset by an orange cross bearing the stylized Greek letters omicron, omega, nu, a common iconographic shorthand for the reply Moses receives on Sinai when he asks God’s name: I am that I am. Over the figure’s shoulder appear the Greek initials for Jesus Christ. The youth’s white gown is like those worn by catechumens about to receive baptism, a sign of his spiritual rebirth. In the upper left, a winged angel, face illuminated by a golden nimbus, gestures toward the icon’s English title inscribed in Greek-like script.

Christ and the penitent are framed inside a symmetric ceremonial arch, a niche of balance, order, and peace. To the left, in contrast, lies a sinister realm of abstracted architectural forms figured in discordant, distorted perspective, a confusion of passageways leading nowhere. This is the world the prodigal son encountered away from home, a secular space both hostile and confounding.

The ruined figure in the doorway rests between a clump of bushy weeds to his left and a floating apparition on his right. Closer inspection reveals a flame burning at the bush’s roots, throwing light but not consuming the plant. The apparition is of a white cross rising from the center of the same sacred bush, penetrating the darkness. The meaning, of a lost soul seated between the Father and Son of the Holy Trinity, is unambiguous.

The painting’s composition moves the eye effortlessly from the face of Christ to the comfort and relief of the son and down, back in time, as it were, to his degradation and summons to redemption. Like the hopes of the lost youth, one’s gaze rises up to the angel, who directs us to meditate once more on the image of the Savior.

A new reality

To reduce Kordis’ icon simply to a masterful technical performance, however, would be to overlook its deeper achievement. Here is Marinis again, from his January comments:

“What is in front of us ... is not just a painting but an icon. ... When a person venerates an icon, they do not venerate the wood or the pigments, but the prototype of the image, to whom the veneration is transferred, in this case, Christ. This relative veneration of the icon and saints is different from the genuine worship of the person depicted and the purpose of this veneration is to arouse devotion.”

Kordis has described this process as one where the figures in the icon move outward toward the viewer, who is invited to move spiritually closer, more fully into spiritual communion. Marinis quotes Kordis on this process:

“The aim of my painting is to create a relationship between the depicted object and the viewer. ... In this way, the beholder becomes part of the artwork and the artwork part of the beholder. Everything in a picture is energy: line, color, movement, and so on. In Byzantine art, these energies are reconciled and exist in a ‘perfect’ way, that is, in a state of dynamic balance.”

On the day of the unveiling, Kordis posted a comment on the YDS Instagram feed. An icon, he wrote, “must …. have inner and external movement in order that it might express and reflect” a relationship of love.

“Through rhythm, images become manifestations of a state of love and create a peaceful space-time here on Earth,” the artist notes in the Marinis extract. “Rhythm transforms everything into a new reality and manifests a desire for a new world where conflict and hatred are replaced with love and peace.”

The “new world ... of love and peace” that Kordis expresses in his icon echoes the “yearning for a final return ... a lasting home,” that Nouwen writes of finding in Rembrandt’s masterpiece. In the aura of these two Prodigal Sons, this shared spiritual hope is aroused in the chapel that bears the name of the revered author, priest, and YDS professor.

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. is a writer specializing in religion and the arts.

![]()