By Mary Clark Moschella

Mary Clark Moschella is the Roger J. Squire Professor of Pastoral Care and Counseling at Yale Divinity School and a trained instructor in the Inside/Out Prison Exchange Program. She wrote the following account of the Inside/Out class held last fall with YDS students and women incarcerated at a federal prison in Connecticut.

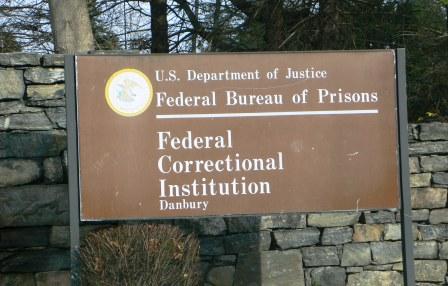

It is once again raining on this Monday afternoon in late fall. I am riding up front next to the driver as she turns the bus full of Yale Divinity School students into the driveway of the Federal Corrections Institute in Danbury. We see fields, empty except for a cut-out image of a black dog waving in the wind. Now the prison buildings come into view, along with an abundance of chain-link fencing and barbed wire. We are dropped off at the entrance to one of the newest buildings on the prison campus. We file in to begin our rituals of entry: filling out forms, exchanging drivers’ licenses for volunteer badges, taking off our shoes to stand on this holy ground.

What, you may wonder, could make a prison holy ground? Only the presence of human beings beloved of God: women who, like the rest of us, have made mistakes; mistakes that they regret. Their mistakes, you may argue, are more serious and harmful than ours; these women must pay for their crimes. I assure you, they are paying. And they are striving to hold on to their souls through years of separation from their loved ones, their friends, their children. (Their children are also paying).

What, you may wonder, could make a prison holy ground? Only the presence of human beings beloved of God: women who, like the rest of us, have made mistakes; mistakes that they regret. Their mistakes, you may argue, are more serious and harmful than ours; these women must pay for their crimes. I assure you, they are paying. And they are striving to hold on to their souls through years of separation from their loved ones, their friends, their children. (Their children are also paying).

The stainless-steel plate on my right tibia sets the alarm off every time. We are screened and wanded and stamped on the wrist. When the entire group of us has made it through, we move as one through a heavy door. We offer our wrists to the ultraviolet light. A buzzing sound allows us to open the door to the outside walkway. As we move through a series of metal gates, we can see the insiders filing over from the building that houses their cells. The women are clad in chino-colored uniforms and standard-issue black boots.

At last we meet in the classroom, which is actually the visitors’ room, surprisingly bright with a view of the distant hills. We have come to study together, to exchange ideas. The students arrange chairs in a circle, don nametags (first names only), and sit down, insider next to outsider. (In the Inside-Out program, incarcerated persons are called “insiders,” and visiting students, “outsiders.”) They mix it up easily by now. They have become fast friends.

The course is “Pastoral Wisdom in Fiction, Memoir, and Drama.” We read a book every week; all students have the same work load. Each writes a reflective paper weekly as well, though the insiders must print their thoughts out by hand. One of the Yale students quietly adopts this practice, in solidarity.

Maya Angelou knew why the caged bird sings. Turns out, so do many insiders. They are humming or singing as best they can, learning to hit the high notes as well as the low ones. A passage from Angelou’s book captures our attention: “At fifteen, life had taught me that surrender, in its place, was as honorable as resistance, especially if one had no choice.” Some questions emerge in the class discussion: If you have been traumatized, how do you know when you have a choice, and when to surrender, just to survive?

The insiders regularly acknowledge that they have made bad choices. The cultural narratives tell us and them that individuals have the power and the responsibility to make good choices. Insiders learn that they are in jail because of their individual moral failures. But what if past experiences of trauma have taught you that it is wise to surrender, to go along, rather than risk challenging the authority of, say, an angry boyfriend? If you are in the room when the drug bust goes down, you are most likely going to be doing time. Still, going along might be the wiser choice, if it helps you survive.

The insiders regularly acknowledge that they have made bad choices. The cultural narratives tell us and them that individuals have the power and the responsibility to make good choices. Insiders learn that they are in jail because of their individual moral failures. But what if past experiences of trauma have taught you that it is wise to surrender, to go along, rather than risk challenging the authority of, say, an angry boyfriend? If you are in the room when the drug bust goes down, you are most likely going to be doing time. Still, going along might be the wiser choice, if it helps you survive.

Maya Angelou seems to be saying that by age fifteen, her life had already taught her how to discern the difference between times to resist and times to surrender. As James Baldwin put it, “Maya Angelou confronts her own life with such a moving wonder, such a luminous dignity…Her portrait is a Biblical study of life in the midst of death.”

The insiders can relate to Maya Angelou’s wisdom. They get the logic of her choices, and they take joy from her story—not only its triumphant outcome—but also its tone, its resonance with their experience, and its determined hopefulness. The women inside know that they must find or forge their own distinct and creative ways of coping, now and in the future. Life has brought them low; they are humble and unpretentious. But they are also strong of mind and determined spiritual seekers. Reading Maya Angelou, they connect to the caged bird and remember the sound of their own voices.

On the bus ride back to the Divinity School, the conversation is quieter, the group of outsiders more pensive. We also find resonance with Maya Angelou’s story, as well as with the stories that the insiders have shared. We feel connected to our sisters who are living in cages. We consider the dignity and strength that these insiders muster to face each day, and, like James Baldwin, we are moved.