By Timothy Cahill ’16 M.A.R.

Peter Hawkins decided to retire the morning he woke with the words of an old Christian hymn on his lips.

His older brother had told him, “When the time comes, you’ll know.” It came when, round and round, the churchy lyric lilted, “Once in every man and nation comes a moment to decide.” To underscore the certainty, there was the timing. The song arrived “either in a dream,” the Yale Divinity School professor recalls, “or in the early waking—when dreams are true.”

Belief in the prophecy of early-morning dreams goes back to the ancients, but for a professor whose course on Dante’s Divine Comedy has become part of YDS lore, it has a particular resonance.

Belief in the prophecy of early-morning dreams goes back to the ancients, but for a professor whose course on Dante’s Divine Comedy has become part of YDS lore, it has a particular resonance.

In Inferno, the first book of Dante’s monumental poem, the poet observes that, “near morning, one dreams the truth,” a point he affirms in his second volume, Purgatorio, writing of “sleep that often, before the event comes, knows the truth.”

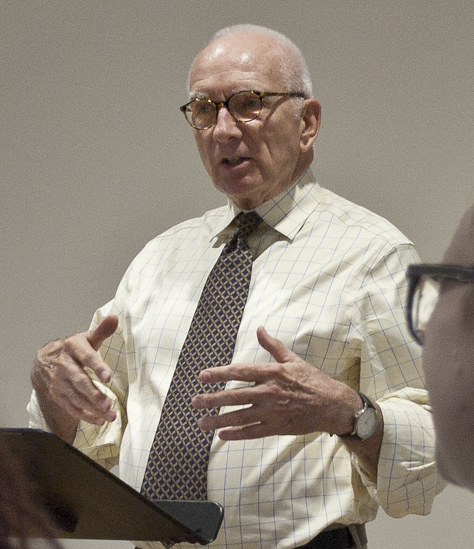

As the fall semester concludes, Hawkins ’75 Ph.D. is bringing an end to 43 years in the classroom, most of it spent at YDS.

Hawkins’ long career at Yale has been marked by triumphs of scholarship, pedagogy, and spiritual mentorship. He founded the school’s Literature and Religion program in 1976, the year he was hired as a 31-year-old Associate Professor, and in the 1980s was one of the original faculty members in the Religion and the Arts program of the Institute of Sacred Music. At Yale, and during a hiatus at Boston University, Hawkins helped shape the study of literature and theology into an international academic discipline.

Hawkins is renowned as a Dante scholar, with five books and numerous articles on the Divine Comedy to his name. But his scholarly work is not limited to “il Poeta.” He has authored books, chapters, essays, and reviews on topics ranging from Flannery O’Connor and women in the Hebrew Bible to the AIDS quilt and Ouija boards. His courses delved into Genesis, the Psalms, the metaphysical poets, the modern short story, and other subjects.

While pursuing teaching and scholarship, Hawkins has also modeled the life of faith and intellect at the core of YDS. He is a longtime member of the communion of Berkeley Divinity School; a reliable presence at daily worship in Marquand Chapel; and one of Yale Divinity School’s most eloquent preachers. In 2006, his homiletic skills were recognized when he was named to deliver the Divinity School’s prestigious Lyman Beecher Lectures on Preaching.

***

RELATED CONTENT: Watch video of Peter Hawkins’ “Wrestling in the River” sermon at 2019 Opening Convocation

***

For all his achievements, however, Hawkins will be best remembered by colleagues and graduates for the way he brought Dante Alighieri alive in his classes, and how he wove the art, theology, mysticism, and splendor of the Commedia into the life of YDS.

Hawkins committed himself to the poem’s labyrinthine genius as a Yale doctoral student, and ever since has been spreading the good news of its treasures. His seminar, Dante’s Journey to God, was for decades one of the most coveted courses at YDS, and for many, one of the most transformative.

“I can’t tell you how many former YDS students I have met who tell me that his course on Dante literally changed their lives in some way,” fellow YDS literature professor Christian Wiman said at a recent dinner in Hawkins’ honor.

“I can’t tell you how many former YDS students I have met who tell me that his course on Dante literally changed their lives in some way,” fellow YDS literature professor Christian Wiman said at a recent dinner in Hawkins’ honor.

I count myself in that group. The seminar was offered every other year, and typically extended over both semesters. For me, however, it came around in a year when Hawkins was scheduled to be away for the spring semester. The professor trimmed the course to fit into thirteen weeks in the fall and led us through the 100-canto, 14,233-line poem at a gallop.

It didn’t matter. Even at that speed, the seminar was a defining experience for me. I would never otherwise have made my way through the entire poem—all of Inferno’s lurid tortures, Purgatory’s seven-story repentances, and the celestial illuminations of Paradise—or, more importantly, have begun to grasp its intricacies. Prof. Hawkins initiated me into the poem’s vast soul, its moral system of order and love, and its ideas of beauty as a portal to the divine, conceptions that define my thinking to this day. I will never be more than a novice in the society of the Divine Comedy, but, like hundreds of fellow students, I had the happy chance to be admitted into the ranks by one of its hierarchs.

I’d been primed for the course by a friend, Mark Koyama ’15 M.Div., who’d taken the full-length class the year before I’d arrived and never seemed to stop talking about it. Today, nearly a decade a later, his enthusiasm for the experience has not dimmed.

“I’ve always said that that class was the highlight of my academic career, for the sheer joy of discussion that was so high-minded,” he told me when I called him up for this story.

As pastor of the United Church of Jaffrey in New Hampshire and English instructor at Northfield Mount Herman School, Koyama fills roles that call on his skills as an educator and guide. His year with Hawkins continually inspires his work.

“I learned two things from Peter that are extraordinarily important to me,” Koyama said. “First, he taught me that teaching is not bestowing knowledge on another person, it’s provoking another person to make their own connections.”

“This is as true of the Bible [while preaching] as it is of teaching poetry or literature,” he continued. “The text is not one plus one equals two. It’s not a matter of defined meaning, but of allowing meaning to come in from as many directions as possible. That’s what Peter is so good at.”

“Second,” Koyama said, “when Peter was talking to you, he was talking to you. You were everything to him at that moment. He wasn’t checking his phone, looking at the time. He would give you all of his attention. That’s something I try to pay forward.”

That experience of Hawkins’ attention and care is shared by David Mahan ’95 M.A.R. Mahan, now director of Yale’s Rivendell Institute and lecturer in Religion and Literature at the ISM, recounted the first day of his Dante class in 1993, when the teacher had the 20 students go around the room and introduce themselves.

“When we’d completed that, Peter remembered every one of our names. I was blown away,” Mahan said.

“He didn’t start by [impressing us] with his knowledge of the [text] or whatever, he started with us. He created the perfect atmosphere for us to begin a journey together.

“Here’s one of the leading Dante scholars in the world. There’s not a question you’re going to pose that he probably has not engaged. But the environment that he created made our own surprises and insights fresh. He affirmed us with that. It was like, ‘I don’t have everything that needs to be said about Dante. You are now part of this conversation, and what you have to contribute matters.’”

“Here’s one of the leading Dante scholars in the world. There’s not a question you’re going to pose that he probably has not engaged. But the environment that he created made our own surprises and insights fresh. He affirmed us with that. It was like, ‘I don’t have everything that needs to be said about Dante. You are now part of this conversation, and what you have to contribute matters.’”

In a sense, Hawkins’ career was a consequence of the Vietnam War.

“A decree when out from Lyndon Baines Johnson that all the world should be drafted,” Hawkins recalled, “and so I went to New York in the summer of ‘68, after the death of RFK and Martin Luther King.” At the time, seminaries were one of the few places a man of graduate-school age could get an educational deferment, so Hawkins enrolled in Union Theological Seminary. He did it, he acknowledges, entirely to avoid Selective Service. But while he was there, he “discovered” the Bible, he says, both the depth of its scriptural truths and its literary lushness. In the fusion of faith and close reading, Hawkins had found his metier. He worked toward his Master of Divinity degree at Union at the same time he pursued a Ph.D. in English at Yale, studying in a department that included Harold Bloom, Paul de Man, and A. Bartlett Giamatti, later President of Yale.

The strands of Hawkins’ destiny came together at Yale when a friend encouraged him to visit a class on the Divine Comedy taught by legendary Dante scholar John Freccero. Listening to Freccero open up the poem, Hawkins felt all his other literary interests recede, including the doctoral dissertation he would go on to write on Spenser’s The Faerie Queene.

Hawkins determined there and then to audit Freccero’s Dante seminar, which occupied a full year—and became the model for his own course years later.

“When I found Dante, it was a perfect merger for me of a richly sensuous text and a journey to God,” Hawkins told me. “It was ready-made for me, my toolbox.”

Influenced by the ways Freccero linked Dante’s poetics to the poem’s medieval theology, Hawkins returned to Union Seminary and wrote his master’s thesis on “theological imagination” in Christian texts, citing Dante as one of his models. In a 2007 essay titled “Laboring in the Vineyard,” Hawkins observed that his Union thesis was his first attempt at combining literature and religion into a single conceptual framework, and “launched me on an interdisciplinary road I have traveled ever since.”

That “interdisciplinary road” was not without controversy when Hawkins applied for a position on the YDS faculty. David Kelsey was on the search committee that considered the young scholar’s application in 1976.

“Yale Divinity School had never had a faculty position dedicated to theology and literature,” recalled Kelsey, a professor of systematic theology at Yale from 1965 to 2005, and now Luther Weigle Professor Emeritus of Theology. “There was some debate as to whether it was even an academic field.”

The matter was settled, Kelsey said, when Hawkins impressed the committee not only with his intellectual gifts, but with his cooperative spirit and affable nature as well.

***

RELATED CONTENT: Read how the AIDS epidemic brought Peter Hawkins out of the closet at Yale in the 1980s (see “life cycle inverted” section)

***

YDS gave Hawkins latitude to develop his specialty in those early years; then, in 1985, he was invited to join the faculty of the Institute of Sacred Music as the ISM expanded its portfolio to include visual art and literature. In partnership with John Wesley Cook, a YDS art historian and the new director of the ISM, Hawkins developed the Religion and the Arts concentrations and team-taught a course titled The Artist as Theologian.

“I learned a whale of a lot from Peter,” Kelsey said. “I increased the spread of my capacity to appreciate what was going on before me and increased the range of my aspirations. I very much admired how Peter went about engaging with a text and with students, in a fashion that was not natural to me.”

His admiration, the theology professor added drolly, “was not lacking in envy.”

In 2000, Hawkins left New Haven to build a Religion and Literature program at Boston University. Eight years later, he happily returned to resume teaching at YDS.

“I find an affection in the classroom here,” Hawkins says. One reason he left BU and returned to YDS, he explains, is that he did not find that same collective feeling at the secular university. “What I remembered happening here at YDS, and what I experience happening here still, is a kind of communion [in classrooms]. We’re all in it together. Sometimes it doesn’t work, but when it does it’s really holy ground. It takes off.”

Studying under Hawkins, David Mahan remembers, “felt as if I were being shepherded through the literature we were studying. In addition to seeing how sublime poetry also does theological work, Peter was the model of how to do scholarship as a guide to others, not as somebody who pushes or forces, but as somebody who clearly leads.”

“He does that out of his love for the work and out of his love for us,” Mahan said.

“Peter effaces himself for the sake of what he loves,” poet Christian Wiman observed in his comments before the faculty, adding that Hawkins enlarges his students’ ideas “of what it means to be alive.” This emerges not merely from the expansiveness of the books that Hawkins teaches, Wiman said, but “also, and inextricably, [through] the man—who is able to be an instrument through which such love can move.”

Greg Sterling, Dean of Yale Divinity School, called Hawkins “a great Yale professor. He is broad in interests, articulate in speech, profound in thought, and a wonderful human being.”

“You can’t replace Peter,” said the Dean about filling the space Hawkins will leave with his retirement. “You find a successor.”

As a devotee of a poem about hell, purgatory, and heaven, Hawkins has long focused his attention on what happens after we leave a place. The Lyman Beecher lectures he delivered in 2006 were an extended meditation on our conception of the afterlife, later published as the volume Undiscovered Country.

“The enormous appeal of other-world imaginings is in part that they open up closed systems and thereby disenchant the status quo,” he writes in the book. “The point … is to open our minds to the good we are not accustomed to seeing, to love the unknown, not to fear it.”

As for the undiscovered country of retirement, Hawkins is fully open. To the question, “What’s next,” he replied, “Discovering what’s next.”

“This has been a wonderful run. I’ve been privileged beyond belief, professionally and personally. But I’m curious about what I don’t know.”

“About life?” I asked. “About yourself?”

“Yes, both,” he answered. “Who am I apart from this? I would like to see.”

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. writes on religion and art. His book Selling Norman Rockwell: Art, Money, and the Soul of an American Museum is forthcoming in 2020.