By Ray Waddle

The movement of the Holy Spirit at Chicago’s historic Trinity UCC Church might sound like John Coltrane, southern gospel, or rapper-producer J Dilla. It might take shape with a cinematographer’s sense of narrative flow and frame. It shows up in pentecostal praise, prophetic preaching, math tutorial classes, and advocacy for a living wage.

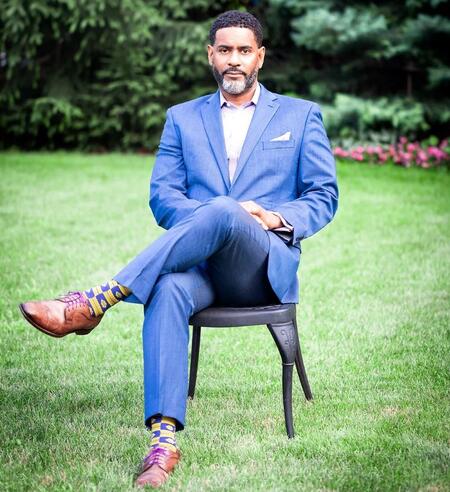

That’s how it goes with the life of the spirit—no boundaries contain it, says Senior Pastor Otis Moss III ’95 M.Div.

At 8,500-member Trinity United Church of Christ, the UCC’s largest congregation, you’ll find sacred attention given to the full humanity of people of color. And to truth-telling in an age of political disinformation. And to the church’s international film festival on justice issues. And to dire trends of mass incarceration. And to pushback against the exploitive algorithms of the attention economy. And to video production on themes of hope and history. And to the grace of God in Christ who “seeks a holy love to save all people from aimlessness and sin,” according to a Trinity mission statement.

In this vision of the faith, pain is turned into art, sorrow into redemption, a blues moan into resurrection. “God is loose in the world,” Moss says. No boundaries.

“Our task is to wrestle with the blues of life, expose the strongholds of national myths, defeat despair, and embody the grace of the Gospel. We are a village of believers who claim the truth that we are made in the image of God.”

This has long been a central theme to Moss, the son of celebrated minister Otis Moss Jr. Otis Moss III calls it the Blue Note gospel message, based on the fervent flow of African American history, struggle, and beauty, a theological mashup that finds Holy Spirit liberation deep inside fierce expressions of art—hip-hop, jazz, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Spike Lee—as well as in the heartfelt hymns and homiletics of sabbath worship.

Moss shared his foundational thoughts on this blues sensibility with the YDS community a decade ago as the 2014 Beecher Lecturer. His subject, which became a book the next year, was “Blue Note Preaching in a Post-Soul World.”

“What is this thing called the blues?” he declared in the lecture. “It is the roux of Black speech, the backbeat of American music, and the foundation of Black preaching. Blues is the curve of the Mississippi, the ghost of the South, the hypocrisy of the North. Blues is the beauty of bebop, the soul of gospel, and the pain of hip-hop.”

The potency of music has been dear to him since his childhood in Ohio, where his sister and brother introduced him to the new sounds of the times, including the scatting techniques of Al Jarreau and the spiritual politics of Marvin Gaye. A later epiphany, in the 1990s, came when he heard visionary producer J Dilla breaking barriers across genres—hip-hop, bluegrass, pop, classical, as well as music from India, Brazil, South Africa. As the millennium was dawning, what Moss heard in the revolutionary beats of “Dilla time” was a new way to do church.

“He changed the way people experience music, and that’s the way church should approach ministry: with a J Dilla vibe,” Moss said. “Expand your crate beyond what you heard as a child and study the structure and beauty of other traditions and as a result create niches that reach people who haven’t been reached before.”

An Otis Moss III (“OM3”) approach to church communication does not take inspiration solely from the polyrhythms of sonic innovation. He grew up wanting to be a filmmaker. He came to see the power of cinematography, the ways a scene can be framed and lit, also the ways a crew on a set must improvise and solve problems to serve the cinematic story. They must collaborate.

“I think anyone in ministry could learn a lot by working on a film set—as a gaffer, a lighter, or any other position. They’d discover that everyone works together. It’s not all about the director or the producer. A good director listens to the crew. People have to listen to each other. It’s an exercise in problem-solving because nothing on a film set goes right! The sun isn’t going to shine the way you want it—you have to make do. It would be interesting to see a change in a seminary curriculum so that people would have to spend time on a set and learn collaboration. That’s a centerpiece of ministry.”

As a young moviegoer it was a revelation to him to see the early films of Spike Lee, especially when Lee worked with cinematographer Ernest Dickerson—notably on Do the Right Thing, Mo’ Better Blues, and Malcolm X.

“I’d never seen anything like it on film,” Moss said. “Black people looking beautiful! Historically, film stock in Hollywood was never designed to film people with darker skin. Traditional American film stock inherently does not light the majority of people in the world properly. Yet by using the right film and lighting we can show viewers the way people actually look. That discovery moved me deeply. As a minister I started asking: how can we ‘frame’ not just the gospel but the virtue of love and justice and light it so people can really see it?”

Film production is a contemporary signature of Trinity’s message to the bigger public world. The church has its own production company, Unashamed Media, which creates documentaries, PSAs, justice-related news summaries, profiles of historic Black figures, training sessions on health and eco-justice, and other media content, often narrated by Moss. The range of projects includes sermonic videos like “Weary Throats and New Songs,” inspired by Teresa Fay Brown’s book by that title on women in ministry; “The Cross and the Lynching Tree,” a requiem tribute to the murdered Ahmaud Arbery; and the music video “Unashamedly Black,” performed by the Trinity Sanctuary Choir. Unashamed Media’s 2020 film “Otis’ Dream”—a dramatization of Moss’s grandfather Otis Moss Sr.’s dangerous attempt to vote in segregated rural Georgia in 1946—has won some 25 awards at national and global festivals. The 14-minute film, with its thematic ties to current threats of voter suppression, has been viewed more than five million times, whether on YouTube or the Oprah Winfrey Network or in public school districts.

Moss and staff are currently working on a film about his father, now 89, and his ministry as a civil rights movement leader, pastor, and speaker. A decade before his son delivered his YDS Beecher talks, Otis Moss Jr. was the Beecher Lecturer—his theme in 2004 was “Preaching as Prophetic Ministry.”

Moss and staff are currently working on a film about his father, now 89, and his ministry as a civil rights movement leader, pastor, and speaker. A decade before his son delivered his YDS Beecher talks, Otis Moss Jr. was the Beecher Lecturer—his theme in 2004 was “Preaching as Prophetic Ministry.”

YDS Dean Greg Sterling attested to the significance of Trinity and its senior minister to the witness of the contemporary church.

“I think that Otis Moss is one of the greatest preachers in the U.S. today. And Trinity UCC is one of the most important churches in the Chicago area—even nationally,” said Sterling, who has attended a service at the church. “It is spiritually dynamic and serves its local community with a very serious commitment. I was there when they were preparing Thanksgiving meals for people in need—hundreds of boxes they were going distribute to their community.”

Their work has been consequential to YDS, too. “They have hired a significant number of YDS alums and they have sent students to us,” Sterling said.

Otis Moss III, a graduate of Morehouse College before coming to YDS, arrived at Trinity in Chicago in 2006 as an assistant to the famed senior pastor Jeremiah Wright, who guided Trinity’s growth to megachurch proportions over the course of nearly five decades. President and Michelle Obama were two of its most famous members (Michelle Obama retains connections with the congregation, Moss said). When Wright retired in 2008, Moss succeeded him, building on his predecessor’s sharply prophetic views on social change and gospel values while addressing a new era of global challenges, including climate crisis, Christian nationalism, and social media anxiety. Moss credits his staff—his “five-star team”—for formulating and executing Trinity’s mission on a variety of fronts.

The church, for instance, has offered Bible study on the urgency of truth-telling in a world of conspiracy-mongering and election denialism.

“Telling the truth begins with knowing one’s self, being honest about the values one holds dear,” Moss said. “If your values are love, justice, grace, humility, reciprocity, and self-examination, then you have the ability to tell a truth that will set you free and others free. But if your roots are predatory self-interest or deeply individualistic and hedonistic, and there’s no humility or self-examination, then you will adopt any lie to promote what you want.”

He has also preached and taught on the spiritual dangers of getting steamrolled by consumer culture. In his Beecher lectures a decade ago, he shared his worry that the legacy of Blue Note prophetic preaching was getting swamped by pulpit messages of false patriotism and prosperity optimism, what he calls “capitalism in ecclesiastical garb.”

Today, he said, he’d update his Beecher remarks to include the danger of this “age of the algorithm,” which threatens to “jettison the blues sensibility for a false sense of security through materialism.”

“The algorithms of corporations benefit from our proclivity to scroll and look for what is the worst in humanity,” said Moss, who is also the author of Dancing in the Dark: Spiritual Lessons for Thriving in Turbulent Times (Simon & Schuster, 2023, with Gregory Lichtenberg). “That’s how the algorithm works—it gets you to scroll, and the worse you feel, the more you scroll. We’re in the midst of a ministry moment where we in ministry need to understand and explain the power of these technologies and the complexities of surveillance capitalism. People are very, very open to change. They have a sense that something isn’t right.”

At stake, he says, is the spiritual and political health of contemporary life—human rights, voting rights, democratic values, also the integrity of the Christian message itself. But he believes no boundaries can stop the vision of a blues-inflected gospel liberation if believers embrace it with courage.

“The Blue Note turns the gospel back to Jesus, the church back to Christ, and the preacher back to the prophets. Christianity was a prisoner of markets, manifest destiny, and men, until the blues set it free to see Christ, Calvary, and the cross once again.”