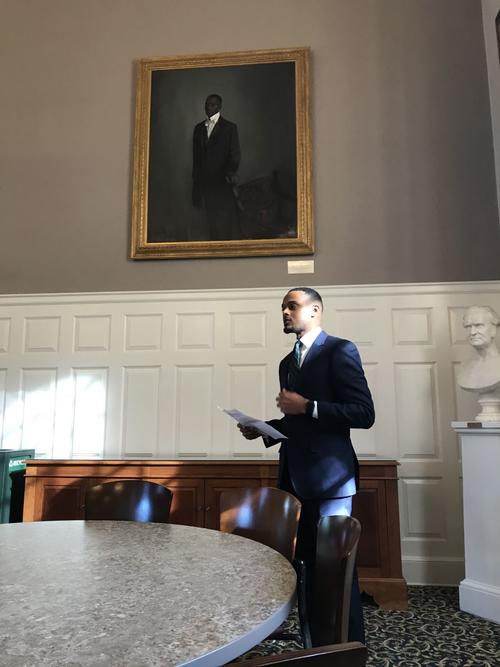

Today, I have been asked to offer remarks concerning what the James W.C. Pennington oil portrait means to me. And while I had no idea who James Pennington was before admittance to Yale Divinity School two years ago, I couldn’t be more proud to know him now. So, to stand before you at this milestone moment for our beloved institution is indeed an honor and a privilege.

As the old adage goes, I stand on the shoulders of James W.C. Pennington, and in the spirit of the millions of ancestors that came before and after him—those who believed that freedom, justice, and human equality were the mandate of God’s self. And, further, that freedom, justice, and human equality as mandated by God meant, and means, the abolition of systems of oppression—namely chattel slavery.

As the old adage goes, I stand on the shoulders of James W.C. Pennington, and in the spirit of the millions of ancestors that came before and after him—those who believed that freedom, justice, and human equality were the mandate of God’s self. And, further, that freedom, justice, and human equality as mandated by God meant, and means, the abolition of systems of oppression—namely chattel slavery.

When I was in grade school, annually, there was a unit in art class on how to use oil pastels. And besides a pretty awful rendering, by yours truly, of Edward Munch’s 1893 “The Scream,” what I remember most from that unit is my art teacher’s insistence that we not get the oil pastels on our clothes, because “oil is a stubborn thing to try to get out!”

When I consider the materiality of oil on canvas; and I consider my art teacher’s warning; and I consider who James Pennington was himself, I cannot think of a more appropriate artistic medium and memorial, for these hallowed halls, than that which is stubborn to get out…

In his memoir, The Fugitive Blacksmith, or, Events in the History of James W.C. Pennington, published in 1850, Pennington wrote “In all the bright achievements we have obtained in the great work of emancipation, if we have not settled the fact that the chattel principle is wrong, and cannot be maintained upon Christian ground, then we have wrought and triumphed to little purpose, and we shall have to do our first work over again.” And what a grave tragedy it is that these words remain relevant almost 170 years after their publishing.

This week, I was graciously invited by the Justice and Reconciliation Department at Trinity Church on Wall Street to join them as a part of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights organization’s city-wide Mass Bail Out initiative. RFK has raised five million dollars to help post bail for women imprisoned at Rikers Island. An initiative to which the city of New York has not taken kindly. Led by Revd. Winnie Varghese, we spent three hours, early Monday morning, posting bail for a poor woman of color accused of a petty crime, but held indefinitely in one of the more dastardly correctional facilities in this country. Later that day, I joined the Trinity staff at a press conference held by the New Sanctuary Coalition—a group of which our very own Rev. Kaji Dousa is a leader and advocate. Joined by faith leaders across several traditions, we heard from Claudia—a mother who has been separated from her 12-year-old son since the federally implemented “Separation Policy” of June 2018.

With all this in mind, when I consider the materiality of oil on canvas; when I consider my art teacher’s warning; and when I consider who James Pennington was, I see not a memorial to that which has been overcome, but a reminder of the long road ahead of us. I am reminded of the abolitionist spirit that says cells and cages are no place for the children of God. I am reminded that, like Pennington, Christians must be stubborn ones which the arbiters of oppression cannot get out and cannot silence.

On some significant level, each of us in this room, I believe, is called to accept the relative power and privilege afforded us by association with this institution, or otherwise. But, we needn’t simply give up that power and privilege in the name of charity and “mere kindness”—for, as Pennington wrote in that same memoir, “…we need something more than mere kindness.” Instead, I pray that this portrait, as an icon in the great Christian tradition depicting the prophets, saints, and martyrs, will inspire us to transform our power and privilege into plowshares with which we might blaze an abolitionist trail of freedom, justice, and human equality mandated us by God God’s self when the Teacher spoke those words from Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to

the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

Thank you.