Editor’s Note: On our social media and website, Yale Divinity School is honoring African American alumnae and alumni during Black History Month. As part of that effort, Moriah Lee ’20 M.A.R. wrote the following brief biography of Samuel Moss Carter ‘30 B.D., one of the institution’s first students of color and an accomplished pastor, teacher, and public figure.

Visit this gallery to learn more about prominent black alumni/ae of YDS. Also watch our posts on Facebook and Twitter throughout February and revisit this 2017 article on efforts by Lecia Allman ’16 M.Div. to recover the history of diversity at YDS.

—

By Moriah Lee ’20 M.A.R.

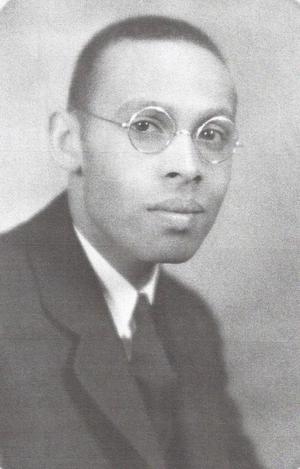

Hailing from three generations of clergymen, Samuel Moss Carter adopted his ancestors’ legacy from an early age. The ambitious Carter quickly became a lauded Baptist minister, working across the eastern United States while also managing to achieve an illustrious academic career at various universities.

Carter’s daughter Symone Scales speaks highly of her father’s nearly lifelong ministry and of his values as a Baptist minister. “He was not your traditional pastor,” Scales says. “He wasn’t a ‘fire and brimstone’ person. He was not an evangelist—he was a teacher. He took his education from Yale and he made it applicable to these individuals who had not been exposed to a lot of education. That was his whole emphasis: ‘You must get educated.’”

Carter’s daughter Symone Scales speaks highly of her father’s nearly lifelong ministry and of his values as a Baptist minister. “He was not your traditional pastor,” Scales says. “He wasn’t a ‘fire and brimstone’ person. He was not an evangelist—he was a teacher. He took his education from Yale and he made it applicable to these individuals who had not been exposed to a lot of education. That was his whole emphasis: ‘You must get educated.’”

Graduating with honors and a B.A. from Ohio State University in 1927, Carter was urged to consider Yale Divinity School by a professor who noticed the young scholar’s academic prowess. It was at YDS where Carter prepared for his future life in ministry, graduating with a B.D. in 1930. He went on to pursue a Ph.D. at Yale, where he wrote a dissertation titled “The Religion of the American Negro Slave,” although he did not complete the degree.

Carter made impressive strides in his career following his study at YDS, first relocating to Raleigh, North Carolina, to work as an Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Shaw University. It was in North Carolina where he met his future wife, Nellie Carter. Together, the dynamic pair inaugurated Carter’s ministerial career, working bi-vocationally for Baptist churches throughout the region.

By his mid-thirties Carter had assumed a pastoral role at the First Institutional Baptist Church in Saint Petersburg, Florida, where he and Nellie welcomed their daughter, Symone Scales, into their family through kinship adoption. “I consider myself having hit the lottery,” Scales says of her parents. “Samuel Moss Carter was a wonderful father and a great husband. I was the only child, and they gave me every advantage they could. I’m very proud of him.” Nellie Carter also gained relative fame in St. Petersburg for opening the city’s first library for people of color, a courageous undertaking in the era of Jim Crow.

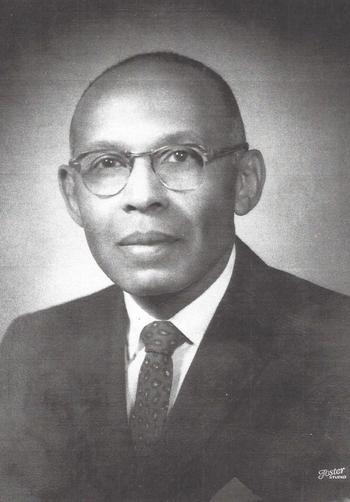

In 1948 Carter was offered a position as Dean of the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology at Virginia Union University in Richmond. Carter served in the role for two years before transitioning into a part-time professorship of Church History and Missions, opting to free more of his time for ministerial work. Carter was soon hired at the local First Baptist Church Centralia, where he taught and pastored for 40 years. During this time Carter also maintained part-time professorial work with the university.

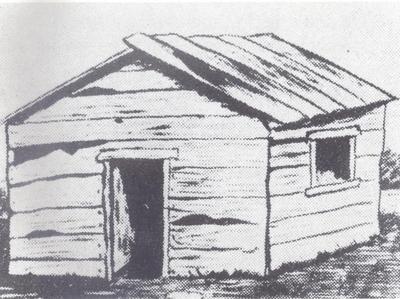

Carter’s longtime congregational home, First Baptist Church Centralia, has a respected and decorated history in its own right. Founded as the Salem African American Baptist Church in 1867—merely two years after the close of the Civil War—the congregation at its start consisted of former slaves from the Richmond area who gathered in small log shelter for worship. Throughout the coming decades the assembly worked tirelessly to secure a more stable location for their growing ministry, a long-awaited dream that Carter helped carry to fruition. Carter’s daughter Scales names his influence in attaining a new building for the assembly one of his greatest life accomplishments, and the church’s website still recognizes Carter’s establishment of the landmark edifice as “groundbreaking.”

Carter’s longtime congregational home, First Baptist Church Centralia, has a respected and decorated history in its own right. Founded as the Salem African American Baptist Church in 1867—merely two years after the close of the Civil War—the congregation at its start consisted of former slaves from the Richmond area who gathered in small log shelter for worship. Throughout the coming decades the assembly worked tirelessly to secure a more stable location for their growing ministry, a long-awaited dream that Carter helped carry to fruition. Carter’s daughter Scales names his influence in attaining a new building for the assembly one of his greatest life accomplishments, and the church’s website still recognizes Carter’s establishment of the landmark edifice as “groundbreaking.”

During his 40-year career at First Baptist Centralia Carter also helped establish a scholarship fund for congregants who felt led to attend university, encouraging many of his parishioners to pursue higher education. “That was his whole thing,” says Scales, quoting her father. “‘You have to reach for the stars—you may fall short, but at least you can’t blame anyone for you not trying.’” The congregation has since erected a Samuel Moss Carter Family Life Center in his honor, a community outreach complex offering educational programs, theological training, youth supervision, a health and wellness center, and other community-oriented services.

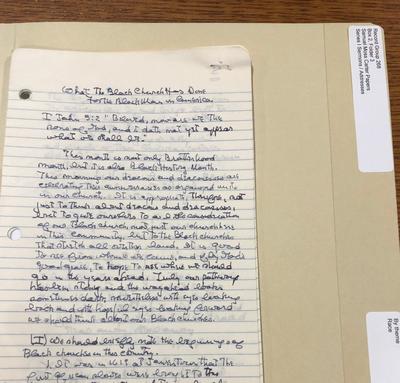

In his academic research Carter held a particular interest in documenting Black Christianity in the Americas, and he incorporated this subject into his many speaking engagements. In a lecture delivered to First Baptist Church Centralia, Carter speaks on the horrific conditions of slavery prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. “Slavery in America was the last stage of a malignant disease from which the human race was ridding itself. And as always the last stage of a disease is the worst. … Slavery did all in its power to unmake men, to rob them of their humanity, to degrade them into brutes; and this it accomplished by declaring them to be property—something that could be used or sold as one pleases. Here was the master evil. Slavery destroyed the conscience of a man. The great right of a man to use, improve, and expand his powers for his own and the good of others. This slavery denied.”

In his academic research Carter held a particular interest in documenting Black Christianity in the Americas, and he incorporated this subject into his many speaking engagements. In a lecture delivered to First Baptist Church Centralia, Carter speaks on the horrific conditions of slavery prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. “Slavery in America was the last stage of a malignant disease from which the human race was ridding itself. And as always the last stage of a disease is the worst. … Slavery did all in its power to unmake men, to rob them of their humanity, to degrade them into brutes; and this it accomplished by declaring them to be property—something that could be used or sold as one pleases. Here was the master evil. Slavery destroyed the conscience of a man. The great right of a man to use, improve, and expand his powers for his own and the good of others. This slavery denied.”

Carter remained a prolific writer and influential thinker throughout his life, transcribing his sermons at First Baptist Church Centralia and furthering his education. In 1957 he earned a Master in Theology from Union Theological Seminary, where he penned his Master’s thesis: “Representative Negro Baptist Preachers.” He was later awarded an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from the institution in 1982.

Carter remained a prolific writer and influential thinker throughout his life, transcribing his sermons at First Baptist Church Centralia and furthering his education. In 1957 he earned a Master in Theology from Union Theological Seminary, where he penned his Master’s thesis: “Representative Negro Baptist Preachers.” He was later awarded an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from the institution in 1982.

Carter died on May 5, 1999. His far-reaching influence is still remembered among family and the many institutions he served. His sermons and biographical papers can be accessed through the Yale Divinity archives.

—-

Moriah Lee ‘20 M.A.R. is interested in the intersection of biblical studies and current theological structures within American evangelical Christianity. She writes as a freelance journalist for Business Insider, with work also appearing in the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News.