By Mike Cummings

Harry “Skip” Stout’s enthusiasm for the study of religion in American life is infectious. Just ask one of his former graduate students.

Catherine Brekus ’93 Ph.D. was a first-year doctoral student at Yale in the fall of 1987 when she took Stout’s course on Puritanism. She’d never taken a course on the study of religion — she arrived on campus planning to study women’s history — but signed up for the seminar after meeting Stout at a picnic for graduate students.

“I am not exaggerating when I say that the course changed my life: It launched my career as a scholar of religion,” said Berkus, a professor of the history of religion in America at Harvard Divinity School. “The course was electrifying. I was not only captivated by the material but by Skip himself — his intellectual curiosity, his energy, his dislike of pretense, his empathetic engagement with the past, and his sheer, unabashed joy in his research. He is exhilarated by the life of the mind.”

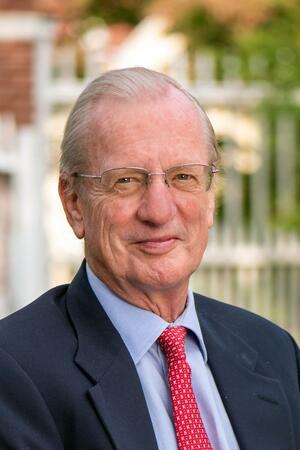

Stout, the Jonathan Edwards Professor of Religious History at Yale and longtime member of the YDS faculty, has had a profound influence on the study of American religious history for nearly five decades, publishing on a broad range of topics, including evangelicalism, Puritanism, the U.S. Civil War, and capitalism. He retired at the end of Spring semester after a 35-year career at Yale.

Stout, the Jonathan Edwards Professor of Religious History at Yale and longtime member of the YDS faculty, has had a profound influence on the study of American religious history for nearly five decades, publishing on a broad range of topics, including evangelicalism, Puritanism, the U.S. Civil War, and capitalism. He retired at the end of Spring semester after a 35-year career at Yale.

He has also been a champion for religious studies. His fundraising efforts with Yale colleague Jon Butler, the Howard R. Lamar Professor Emeritus of American Studies, History, and Religious Studies, yielded hundreds of research grants for early-career scholars at the university and across the country. As general editor and director of Yale’s Jonathan Edwards Center, housed at YDS, he was instrumental in making the works of Jonathan Edwards, the renowned 18th-century American revivalist preacher, philosopher, and theologian, accessible to scholars worldwide.

So, too, has he strengthened intra-university ties. “Skip has been an invaluable liaison between the Religious Studies Department and the Divinity School as one of the faculty who have an appointment in each,” YDS Dean Greg Sterling said.

For Stout, the importance of studying religion’s influence on history and contemporary life is self-evident.

“All you need to do is to look at the world today, and you’ll quickly realize that religion is somehow involved in virtually every major movement and every major controversy across the globe,” he said. “We’ve got to get this story straight and share what we learn. Perhaps, it will create a greater understanding and comity among the world’s religions.”

‘Intellectual power’

Stout brings a unique sense of mirth to his teaching and scholarship, said FAS Dean of Humanities Kathryn Lofton, the Lex Hixon Professor of Religious Studies and American Studies. And he is always willing to support and encourage junior faculty.

“My life changed the day that I met Skip,” she said. “From the moment we met, Skip treated me like an equal and taught me how to see myself as a leader, and not a junior faculty member, and to treat my scholarship as something worthy of that standard.”

Molly Worthen ’03 B.A. ’11 Ph.D., an associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and one of Stout’s former graduate students, echoed Lofton’s sentiments. By treating his students as peers, she said, Stout both put them at ease and encouraged them to show that they merited his trust.

“It had real intellectual power,” she said. “It forced us to act confidently and that’s how you become confident.”

Stout, who was head of Berkeley College from 1990 to 2001, said his fondest memories of Yale involve interactions with students, both graduate and undergraduate.

Stout, who was head of Berkeley College from 1990 to 2001, said his fondest memories of Yale involve interactions with students, both graduate and undergraduate.

“Being head of college affirmed my high opinion of the students both in terms of their abilities and, in most cases, their humility and modesty,” he said.

As much as Stout relished teaching, he also enjoyed his research, producing a steady stream of scholarship that stretched the bounds of his field. For example, he was one of the first historians of religion to examine the role of media in spreading religious beliefs, Lofton said.

“Before it became an area of strong interest within the field, Skip was examining the significance of media in the form of the sermon, but also pamphleteering, newspapers, and newsletters,” she said.

Unlike most scholars, who choose areas of specialization, Stout pursued difficult questions concerning varying subjects that seized his interest. His 2007 book, “Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War,” for instance, explored the moral issues raised by America’s bloodiest conflict.

“For all of the work done on the Civil War — it seems like a book has been written about it every day since Appomattox — no one paid very close attention to the moral dimensions of the war,” he said. “I applied just war theory to the treatment of civilians and the proportionality of the enormous number of casualties. It felt like a book that needed to be written, and I’m glad it’s behind me.”

Since 1991, Stout has been general editor of “The Works of Jonathan Edwards” (Yale University Press), a 26-volume collection of the famed preacher and Yale alumnus’ treatises, sermons, letters, and musings. Sterling praises Stout for leading publication of the Edwards corpus “in an exemplary and efficient manner,” adding, “Skip is by any standard of measurement an extraordinary scholar.”

Stout, who had postings with the Department of History and Department of Religious Studies in addition to YDS, reflects that “Edwards is often associated with terror because of his infamous sermon ‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,’ but he was much more concerned about beauty and what he called ‘the sense of the heart.’ He is easily one of the most significant American intellectuals before 1800.”

Through the Jonathan Edwards Center, Stout raised funds to digitize Edwards’ immense corpus, making it available to anyone with an internet connection. He helped oversee the establishment of satellite research centers in 10 countries on five continents devoted to facilitating the study of Edwards.

Helping scholars is a hallmark of Stout’s career. With Butler, he secured funding in the 1990s for grant programs that gave graduate students and postdoctoral scholars the chance to tackle novel questions.

“We wanted to jumpstart the study and appreciation of religion in American life, and the best way to do that is to offer money for research,” said Stout, who chaired the Department of Religious Studies from 2005 to 2009. “In some sense, we were in the business of bribery.”

“We wanted to jumpstart the study and appreciation of religion in American life, and the best way to do that is to offer money for research,” said Stout, who chaired the Department of Religious Studies from 2005 to 2009. “In some sense, we were in the business of bribery.”

Many of the scholars who received grants are now leaders in the field, Lofton said.

“Skip wants young scholars to succeed and be brave; to take on the biggest questions and to take the time to answer them,” she said. “He is also always there to witness a political difficulty and intervene on behalf of the person who is in a diminished role of power. Using contemporary language, he is an ally, who took a strong role in bringing the religious studies department into the 21st century.”

The research continues

Although Stout’s days advising graduate students have ended, his research continues. He is working on two book projects: One is a biography of Timothy Dwight, the theologian and eighth president of Yale College, that will draw on a trove of primary source manuscripts recently acquired by Yale’s Divinity Library. The other is a cultural biography of Sarah Pierpont Edwards, Jonathan Edwards’ wife, which he is co-authoring with Brekus and Kenneth Minkema, another of his former doctoral students.

The book uses a memoir of Sarah Edwards, also recently acquired by the Divinity Library, to explore early American attitudes toward the body, gender, ecstatic worship, and religious authority. It will provide a different picture of Edwards than the demure and measured wife portrayed in the historical record, Stout said.

“The memoir shows Sarah to be ecstatic, almost levitating, during a period of a couple of weeks in 1742,” he said. “So that’s going to be the nucleus of the book: The Sarah that nobody has really seen before.”

For her part, Brekus is happy to be working with her former mentor.

“I have spent my career trying to be the same kind of doctoral adviser to my students as Skip was to me,” she said. “I am deeply grateful for his brilliance, his mentorship, his kindness, and his friendship.”

Mike Cummings is a writer in Yale University’s Office of Public Affairs and Communications.