By Janet Davenport

When Shelley Best ’00 M.Div. entered Yale Divinity School, she was on a quest to find an elusive answer: How could she make it financially viable to devote her ministry career to serving poor people? An ordained minister with a master’s degree in religious leadership from Hartford Seminary, she was determined to continue pursuing her calling despite serving a church that could not compensate her monetarily. Best figured if a contemporary Christian model for serving the poor and making a living existed, she would surely find it at YDS. She was wrong.

But Best did not graduate empty-handed or disappointed. Commuting for two years between Torrington―a blue-collar town cradled in the hills of northwest Connecticut―and New Haven built stamina and spiritual endurance. Professors such as her mentor, the late feminist theologian and author Letty Russell, challenged and pushed her beyond the margins of her perspective. Russell also boosted Best’s confidence and reaffirmed her agency as a female scholar in the predominately white male academy. She sharpened and refined her creative and critical thinking. These turned out to be exactly the skills she needed to invent the 21st century models of ministry she was seeking.

But Best did not graduate empty-handed or disappointed. Commuting for two years between Torrington―a blue-collar town cradled in the hills of northwest Connecticut―and New Haven built stamina and spiritual endurance. Professors such as her mentor, the late feminist theologian and author Letty Russell, challenged and pushed her beyond the margins of her perspective. Russell also boosted Best’s confidence and reaffirmed her agency as a female scholar in the predominately white male academy. She sharpened and refined her creative and critical thinking. These turned out to be exactly the skills she needed to invent the 21st century models of ministry she was seeking.

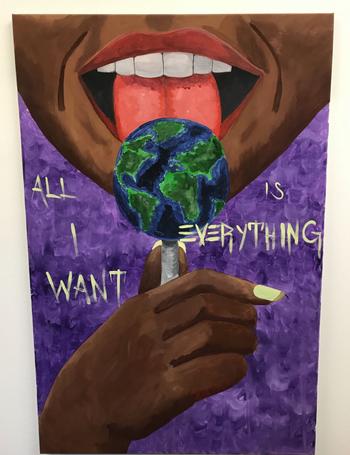

That was almost 20 years ago. Naturally, Best’s thoughts turned to Russell and a host of other Yale memories this past fall when she returned to the Divinity School to share the latest creations from the artistic side of her multifaceted ministry. Sixteen of her abstract paintings collectively titled “What is Black?” are part of a provocative new art and photography exhibit that debuted in November at the Divinity School.

Aptly titled “Audacious Agency,” the touring exhibition features an eclectic mix of unique pieces intended to spur dialogue about the urgent social, economic, political, and religious issues facing communities of color. In addition to Best, the group comprises photographer Keith Claytor and painters Zulynette, Andre Rochester, and Patrick “Rico” Williams.

Their activist-centric oeuvre will be on display at the Divinity School through February 2019. From there, it will tour Connecticut, New York, and other yet-to-be determined sites.

Best, the sole minister in the group, describes her designs as “preaching without words.” The geometric patterns in her pieces exhort viewers to examine skin color, identity, and prejudice through the filter of the Pantone colors used in graphic arts. “Using the continuum of color, every color found in human skin could be black if that is how you identify,” Best said. She was inspired by the Humanae Project of Brazilian photographer Angélica Dass, who photographed over 4,000 people from around the world and matched their skin color with Pantone colors.

Best, the sole minister in the group, describes her designs as “preaching without words.” The geometric patterns in her pieces exhort viewers to examine skin color, identity, and prejudice through the filter of the Pantone colors used in graphic arts. “Using the continuum of color, every color found in human skin could be black if that is how you identify,” Best said. She was inspired by the Humanae Project of Brazilian photographer Angélica Dass, who photographed over 4,000 people from around the world and matched their skin color with Pantone colors.

***

Event notice: An Audacious Agency artists talk will be held at YDS at 6 p.m. on Thursday, Jan. 31.

***

“Black is a social construct,” Best said—a construct shot through with damaging myths and lies. “Anyone can be black. As Christians, we miss so much when we insist on holding on to the lunacy around skin color,” she said during a recent interview, adding, “It’s definitely an area for prayer.”

Seated in her book-lined office in Hartford, Best, the president and CEO of the Conference of Churches—the first woman to hold the position—paused to reflect on her 30-year theological journey as an activist-artist, minister, and social entrepreneur. Her career-long commitment to confronting gender, race, and class finds a culmination in the new exhibit—and in its debuting at YDS. “We wanted to start these complex conversations in a unique space,” Best explained. “We thought it would be important to reach viewers who are seriously examining these issues. Ultimately, we’re all affected by them.”

Seated in her book-lined office in Hartford, Best, the president and CEO of the Conference of Churches—the first woman to hold the position—paused to reflect on her 30-year theological journey as an activist-artist, minister, and social entrepreneur. Her career-long commitment to confronting gender, race, and class finds a culmination in the new exhibit—and in its debuting at YDS. “We wanted to start these complex conversations in a unique space,” Best explained. “We thought it would be important to reach viewers who are seriously examining these issues. Ultimately, we’re all affected by them.”

The School’s own struggles with race, gender, and diversity notwithstanding, Best credits YDS for opening doors for her to confront racism and sexism in white, liberal, social-change environments, including the faith and nonprofit sectors. “The model of liberalism with white people doing the work on behalf of black and brown people needs shifting,” she said. “It is far more empowering to involve people in the decisions affecting their lives and communities. People of color should be at the table.”

“As an activist, Yale gave me access to the privilege, resources, and influence that the communities I choose to serve simply do not have. It credentialed me as an African-American woman to reach beyond my denomination,” she said.

‘Truly empowering ministry’

For an example of the faith-based community development and empowerment model of ministry that Best preaches, one need look no further than EcoSpace, owned and operated by the Conference of Churches. The 30,000-square-foot building located on the city’s bustling Farmington Avenue is home to an art gallery, dance and yoga studios, a conference center, and coworking spaces for entrepreneurs and business start-ups. It’s adjacent to a community garden. Last November, the Harford Business Journal lauded the enterprise as one of the most distinctive office spaces in the city. Built as a garage and turned into an art center in the ’80s, it was left vacant for years before its current embodiment.

Best’s most significant “installation” to date, EcoSpace provides a vibrant platform for artists, healers, activists, and entrepreneurs from all cultural and faith backgrounds to work together. “People from all walks of life feel something different when they come here. The ‘it’ is the faith factor, whether people are believers or not,” Best said, adding that the development of the EcoSpace was nothing short of a miracle itself.

Best’s most significant “installation” to date, EcoSpace provides a vibrant platform for artists, healers, activists, and entrepreneurs from all cultural and faith backgrounds to work together. “People from all walks of life feel something different when they come here. The ‘it’ is the faith factor, whether people are believers or not,” Best said, adding that the development of the EcoSpace was nothing short of a miracle itself.

The idea for the space and its programs and services was born of Best’s vision of 21st-century model of ministry. Food and clothing drives, soup kitchens, and other services to help people get on their feet are important, Best said. However, citing the famous quote by the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu about the advantage of teaching people to fish over feeding them fish, she said the Ecospace model moves beyond handouts. “We wanted to equip people to create more positive futures for themselves. This is truly empowering ministry,” Best said.

As she and Lydell Brown, vice president of operations, shepherded the initiative, it was met with some resistance along the way, including from several board members who had more traditional notions of Christian service. Best and Brown forged ahead.

As she and Lydell Brown, vice president of operations, shepherded the initiative, it was met with some resistance along the way, including from several board members who had more traditional notions of Christian service. Best and Brown forged ahead.

In 2013, the White House Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships program invited the Conference of Church to present its social entrepreneurship model at a gathering of policymakers. Best sees the invitation as an example of how the rapidly changing times have caught up to her vision and theological framework. “When you have to stare dead in the face of brokenness, it forces you to open the door to new models of ministry,” she said, reflecting on those early lessons from her first pastoral calling at the church in Torrington. “I learned early on that I would have to redefine ministry and create new paradigms for Christian service.”

The changing nature of congregational ministry and the blurring lines between “ministry” and secular vocations is changing the way divinity scholars view their futures. The Association of Theological Schools, of which Yale is a member, conducted a survey last year of graduating students. It found that only 41 percent planned to serve as pastors or associate pastors of a congregation or parish.

More than 10 percent of the students told ATS they were unsure of their vocational goals, whether within or outside a congregation or parish. The other 49 percent of graduates reported plans to serve in a wide array of ministry and non-ministry settings, ranging from hospital chaplains to teachers, nonprofit administrators, and lawyers.

As increasing numbers of faith leaders and scholars seek insights into self-empowerment and more diverse models of ministry, editors from Feminist Studies in Religion commissioned Best to write a how-to book. Scheduled for publication in 2019, the book is tentatively titled “Soulpreneurs and Womanish Ways of Working: A Womanist Practical Theology and the Creation of the 224 EcoSpace.”

“I’m thankful for the privilege of studying at Yale,” reflects Best, who is an ordained elder in the A.M.E. Zion Church and pastor of the Redeemer’s A.M.E. Zion Church, a small, family-oriented church in Plainville, Conn. “Being able to put that scholarship into practice has been a blessing. It’s an honor to find myself in the role of practitioner and witness and exciting to have a chance to share how to do this theological work.”

Writing the book compelled Best to retrace her steps and reexamine the spiritual infrastructure and faith that undergird Ecospace, as much a hub for the performing arts and small businesses as it is a healing and wellness space for the community. As for the future of the EcoSpace and her evolving definition of ministry, Best points to the EcoSpace’s early tagline. “The possibilities,” she said, “are endless.”

Janet Davenport is a Hartford-based communications consultant and a cohort member in the Yale Clergy Scholars Program.