By Ray Waddle

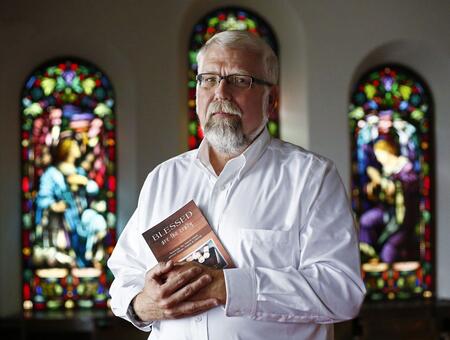

What makes someone a “genius” at justice? The Rev. Timothy Ahrens ’85 M.Div. has been pursuing that question with a genius of his own for decades, collaborating with justice advocates across the landscape, honoring them in his own life, and even getting them on the phone to pinpoint the moral X factor of what they do.

In 2021, Ahrens began conversations (by Zoom and face-to-face as well as over the telephone) with 53 remarkable activists of justice—mentors, friends, and co-leaders who embody biblical teaching and tireless advocacy. Justice work, he confirmed, is unapologetic, cross-racial, cross-cultural, communal, personal, nonviolent, unshakeable. It hears the biblical command to walk humbly with God and dignify people who go neglected, malnourished, undetected. Justice is a fearless forethought, never an afterthought.

In 2021, Ahrens began conversations (by Zoom and face-to-face as well as over the telephone) with 53 remarkable activists of justice—mentors, friends, and co-leaders who embody biblical teaching and tireless advocacy. Justice work, he confirmed, is unapologetic, cross-racial, cross-cultural, communal, personal, nonviolent, unshakeable. It hears the biblical command to walk humbly with God and dignify people who go neglected, malnourished, undetected. Justice is a fearless forethought, never an afterthought.

“A genius of justice sees a person who others have not seen,” Ahrens writes in his recent book The Genius of Justice (Cascade Books, 2022), in which he shares what he learned from his research. “She hears the person who has not been heard. … They don’t use the word justice in the back half of a sentence, in a whisper, with a question mark. They lead with justice. They have a twinkle in their eye and a hop in their step. They have steel in their spines.”

Ahrens is senior minister of First Congregational UCC in Columbus, Ohio, where he carries forward a social gospel identity that is now nearly 150 years old at his church. Washington Gladden, a 19th-century founder of the American social gospel movement, was minister there from 1882 to 1918, thundering against labor abuses and racial inequalities, insisting that economic issues are spiritual issues, and salvation is a social as well as a personal matter. A Washington Gladden Social Justice Park, sponsored by the church, is located nearby. A First Church motto proclaims: “No matter who you are or where you are on life’s journey, you are welcome here.”

Today Ahrens is a passionate teacher of scripture, a mobilizer of statewide interfaith initiatives, and a familiar figure at the Ohio Statehouse, where he has led many a demonstration over the years for fair labor practices, gender equality, healthcare reform, and housing access.

“As Washington Gladden wrote, religion is nothing more than friendship—with God and other human beings,” Ahrens says. “Gladden was a genius of justice and so much more. He understood that relationships are at the heart of real change.”

Ahrens features such friendships in the book, weaving their personal stories with pragmatic summonses to action. His roll call of 53 includes pastors, rabbis, professors, capital punishment opponents, NGO execs, physicians, and sages. Two on the roster are from the same family: the Rev. Otis Moss Jr, Ohio minister and pivotal civil rights advocate, and his son the Rev. Otis Moss III ’95 M.Div., senior minister of Trinity UCC in Chicago, where he is known for his prophetic imagination and use of hip hop, jazz, film, and art to connect people to justice, joy, and fulfillment.

“One can see, among these several bold agents, some recurring elements in their lives,” biblical interpreter and author Walter Brueggemann says in the foreword to Ahrens’ book. “They were nurtured in families with an emancipatory perspective, they were early on situated in a peculiar angle of vision so that things are seen differently, they have been often mentored in ways that triggered vision and courage, they grew into a sense of urgency, and they are willing to invest in quite local social reality.”

Ahrens grew up outside Philadelphia as a churchgoing kid who played basketball in high school. As far back as he can remember, his heroes whether in sports or politics were people of color—Martin Luther King Jr. and Hank Aaron, Fred Shuttlesworth and Julius Erving, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Jackie Robinson.

“I read their stories—I wanted to be them,” he recalls. “As I was growing up, Dr. King was the only Christian who made sense to me.”

On the walls of his study today are pictures of Breonna Taylor, Riah Milton, and Oluwatoyin Salau—martyrs of the violence against women of color—as well as other Black heroes. Ahrens gives credit to the Holy Spirit for stirring in him a long commitment to antiracism.

“As a white man, I know that I can walk away from these issues of racial injustice any day at any time. That is white privilege. It’s real,” he writes. “I have made a vow to be an antiracist every day.”

His activism kicked into high gear when he was an undergraduate at Macalester College—notably in a summer job in a struggling St. Louis neighborhood, where he was a group leader for 75 young children of color.

A decisive moment came at the end of that 1979 summer stint, when a six-year-old boy gave him a farewell hug and said, “Have a nice life.” Ahrens, startled, asked why he phrased his goodbye so starkly. “Well, white people never come back here,” the youngster replied. Ahrens recalls: “I told him I’ll come back, and I did come back the next summer. I was called to ministry in that moment. I felt a sense of the Holy Spirit working through that child.”

Before he came to Yale, Ahrens also spent a year or so in an intentional living community in downtown Philadelphia called Jubilee Fellowship, an evangelically minded group akin to Sojourners and dedicated to prayer, worship, and serving the neighborhood.

With ordained ministry in his plans, he considered 13 seminaries before arriving at YDS in 1982.

With ordained ministry in his plans, he considered 13 seminaries before arriving at YDS in 1982.

“I didn’t go to Yale to activate—I was an activist already,” he says. “I went to Yale to have scholars sit me down in front of them and teach me how to think. I wanted to learn this faith from the best.” His YDS teacher-mentors would include Margaret Farley, Letty Russell, Cornel West, David Kelsey, Brevard Childs, Bonnie Kittel, and Joan Forsberg.

He nevertheless could not put activism totally aside in his semesterly routine. He spent part of his senior year on the picket line outside the gates of YDS, helping to organize students in support for the historic 1984 strike of Yale clerical workers, mostly underpaid women. He somehow managed to get his classes to meet outside and off campus in a show of solidarity. The strike, settled in early 1985, is still cited by labor historians as an extraordinary victory for U.S. worker justice.

In 2008, YDS honored Ahrens with the William Sloane Coffin ’56 Award for Peace and Justice. As a famous Yale chaplain and a national agitator for social change, Coffin ’56 B.D. was one of those “true saints of God” who has buoyed Ahrens’ life, fighting for biblical values in defiance of dire trends of inequality, political division, and environmental threat. Fueling his book, Ahrens says, was a sense of gratitude for figures like Coffin who provide an “elixir of hope” for the future of humanity, the future of earth, and the life of faith against the odds.

“They follow the voice of their God and the inspiration of their ancestors,” he writes. “They do not yield in the face of what is wrong. They never give up. They never give in. They live in hope even on bad days.”

His experience arms him with a measure of resilience as church and society navigate an era of ordeal and heartbreak. A case in point is the uncertain state of churches as they seek an exit out of pandemic times. Ahrens said the “three thirds” formula describes his congregation and many others: one-third have returned to in-person worship, one-third are on the fence about committing to church life, and one-third connect with the church strictly online. First Congregational actually grew during the pandemic, mostly because of new online visitors and adherents.

“That online ‘one-third’ is the greatest hope for the churches,” he says. “How many of these online viewers are taking the learnings they hear at church and living them out? Isn’t that what we’re hoping for? Every congregation I know of is working on these questions every day. There’s no doubt the online component is here to stay. We have a livestream ministry at our church now. We’re training our teens to do it. The marks of this trend are all good, the value it brings. No one wants to go back to the pre-pandemic pattern.”

Perhaps more concerning to him is the tattered state of national unity. Polarization has become an easy default position. “People give up easily now,” he says. “We’re not in the rooms together anymore! People don’t stick around to hear an opposing view. They can retreat to the news channel they want, get the social media fix they want, or find a church that serves all their political views. I believe reconciliation happens when we’re singing the same hymns and saying the same prayers and confessing to God in the same way. I think what we’re really missing is biblical teaching, a rediscovery of what the Bible really says about justice and reconciliation.”

Ahrens’ sense of divine possibilities in the eventful 21st century can be found in the 53 geniuses of justice he profiles—their drive and desire to “overcome the disorder of this world and set us right again.” Toward the end he adds two more names. Number 54 is “the Other”—all those who have been left behind or dismissed as alien but whose work for justice is full of power and grace. The 55th name on the roster? That would be the rest of us, if we will make the decision “to join the movement for change.”

“I believe in you,” he writes. “There is no time to waste. The world needs you now. I believe you will do the right thing. I am here to walk with you. The geniuses of justice are all here, too. We are excited you have stepped forward to change the world. Let’s get moving.”