Story and photos by Timothy Cahill ’16 M.A.R.

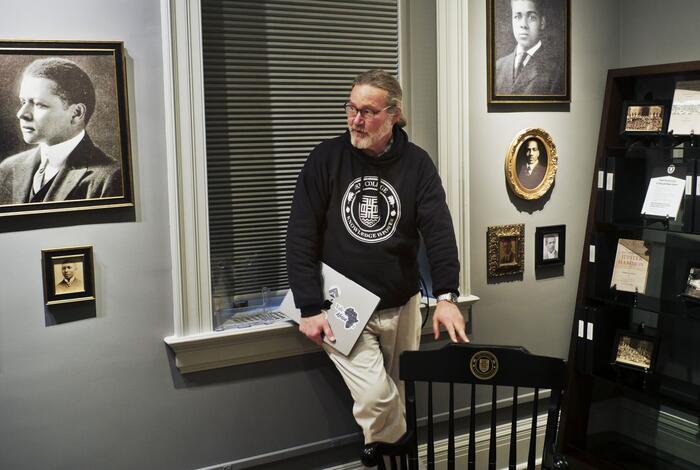

Michael Morand ’87 B.A., ’93 M.Div. greeted nearly a dozen staffers of the New Haven Museum who had been assembled in their Whitney Avenue building for an informational tour of the new exhibition he had organized. His long, graying hair was bunched and tied behind his head, and he wore a black hoodie emblazoned with the seal of the “1831 College” and motto “Knowledge is Power.” His affable expression hid nearly all of the slightly frayed concentration of a curator in the final hours before the opening of a show.

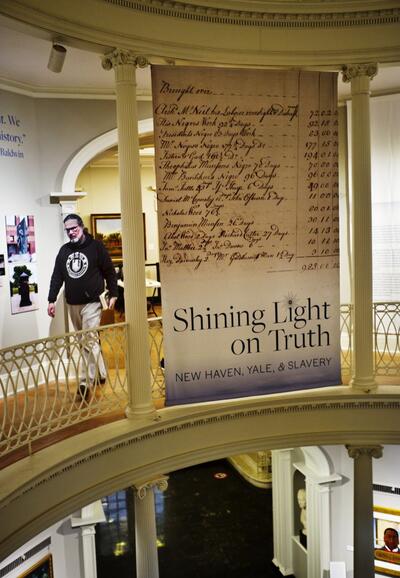

The exhibition, “Shining Light on Truth: New Haven, Yale, and Slavery,” is installed in one of the museum’s most prominent spaces, the colonnaded rotunda gallery that graces its second floor. It features historical documents, photographs, and archival ephemera that combine to create a pointed and poignant meditation on the links between the city, the university, and the legacy of Black enslavement. The exhibition runs through the summer.

The exhibition, “Shining Light on Truth: New Haven, Yale, and Slavery,” is installed in one of the museum’s most prominent spaces, the colonnaded rotunda gallery that graces its second floor. It features historical documents, photographs, and archival ephemera that combine to create a pointed and poignant meditation on the links between the city, the university, and the legacy of Black enslavement. The exhibition runs through the summer.

Morand, Director of Community Engagement at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, organized the show as part of the Yale and Slavery Research Project, which arose from a 2020 summons by President Peter Salovey for Yale to reckon with its historical ties to slavery. The museum exhibition coincided with the February publication of Yale and Slavery: A History by David W. Blight, Sterling Professor of History and African American Studies, written and edited with research project colleagues Hope McGrath and Morand. The book was released alongside a companion website, videos, and audio walking tour, accessible from yaleandslavery.yale.edu.

Blight, author of the Pulitzer-winning biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, is unequivocal in the new book. Its opening sentence declares, “A multitude of Yale University’s founders, rectors, early presidents, faculty, donors, and graduates played roles in sustaining slavery, its ideological underpinnings, and its power.”

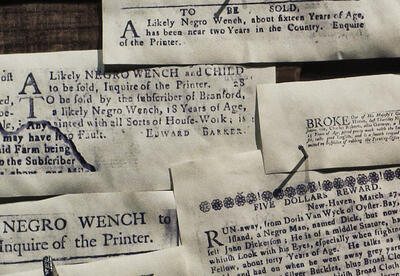

The exhibition is steeped in the same unvarnished truth. A floor label at the threshold of the rotunda alerts visitors, “Please be advised this exhibition contains complex and challenging text and images.” It’s a point Morand reiterated as he led the museum staff through the show. “There’s some tough language” here, he said, indicating a display of rough-sawn boards posted with a blizzard of public notices reproduced from early New Haven newspapers. The announcements offer rewards for runaway slaves or advertise “Negro” “wenches” and “servants” for sale. They read like malign odes to centuries of callousness toward slavery and racism. One brief bill announces: “To Be Sold: Two building lots in New Haven Township, which face three streets; likewise a young Negro lad.”

The exhibition transforms the abstract into something very real, “This is about human beings,” Morand said of the exhibition. “It is sanctified work.”

This evocation of sanctity reflects a life twined by faith and opposition to racial injustice. Morand studied liberal arts at Yale College and earned a Master of Divinity degree from YDS. He has deep ties to the New Haven Black community and church and credits his husband, scholar and author Dr. Frank Mitchell ’89 M.A., and their longtime mentor, the late Rev. Samuel Slie ’52 B.D., ’63 S.T.M., as among his greatest teachers. His talk is rich with Biblical allusions, an influence that goes all the way back to his teen years at a Jesuit high school in Cincinnati. Over his four decades at Yale and in New Haven, Morand has been both a social activist and a public servant. He served two terms on the New Haven Board of Alders and led the Board of Directors of the New Haven Free Public Library.

This evocation of sanctity reflects a life twined by faith and opposition to racial injustice. Morand studied liberal arts at Yale College and earned a Master of Divinity degree from YDS. He has deep ties to the New Haven Black community and church and credits his husband, scholar and author Dr. Frank Mitchell ’89 M.A., and their longtime mentor, the late Rev. Samuel Slie ’52 B.D., ’63 S.T.M., as among his greatest teachers. His talk is rich with Biblical allusions, an influence that goes all the way back to his teen years at a Jesuit high school in Cincinnati. Over his four decades at Yale and in New Haven, Morand has been both a social activist and a public servant. He served two terms on the New Haven Board of Alders and led the Board of Directors of the New Haven Free Public Library.

‘Georgia of New England’

The exhibition was conceived “to give people an embodied experience with the material” in the book, Morand explained. Curated by him with Charles E. Warner, Jr., and designed by David Jon Walker MFA ’23, the show animates the written history with tangible evidence culled from historical collections, archives, and databases. As a venue, the New Haven Museum, with its galleries spanning every aspect of regional history, adds four centuries of context to the story.

“This is a Yale story that is also a New Haven story that is also a Connecticut story,” Morand observed. “New Haven was Connecticut and Yale was New Haven.”

Connecticut, which abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison once derided as the “Georgia of New England,” was the last New England state to abolish slavery, in 1848, its urban economy being intimately tied to the slave trade. Connecticut merchants sold goods to the slave plantations in the West Indies, and Connecticut businesses insured enslaved people as property. Many of those traders, merchants, and businessmen were sons of Yale.

Wall texts describe a history of complicity as tangled and pernicious as an invasive vine. The very name of the university was changed in 1718 to honor early donor Elihu Yale, whose fortune was made in part from the sale and export of enslaved people. Men as essential to Yale’s history as Benjamin Silliman (after whom one of Yale’s original residential colleges is called) and James Hillhouse (whose name is on the street where the President’s residence is located) are called out not for their contributions, but for their involvement in selling or owning other humans.

Another class of person is exposed in the exhibition as well: Black men and women whose identities until now had been buried under centuries of white disregard. The exhibition begins with a list of more than 200 names of individuals enslaved by the leaders of Yale in its first century. The display, simple printed lists in heavy wooden frames, was conceived, Morand said, “to give dignity and presence” to people recorded as single names only, or no distinct name at all. “We hope people will interact with this in a reverential way.”

This imperative to speak their names is manifested throughout the exhibit. Thus, visitors are introduced to “Jack,” “Mingo,” and “Dick,” enslaved men who in 1752 helped build Connecticut Hall on Yale’s Old Campus, the oldest surviving building in New Haven. They learn of Mary Ann Goodman, a Black woman who in 1871 bequeathed the equivalent of nearly a quarter-million dollars to Yale to train “young men of color” for the ministry. High on the walls are oversized quotations from the likes of Alexander Crummell ’23 M.A.H., Yale’s second Black student, and Jacob Oson, America’s first great Black historian, like raised voices of hope and courage.

“It’s not as if this is hidden history,” Morand said of the information presented on the walls. “It’s there for anyone who wants to look.”

The 1831 College

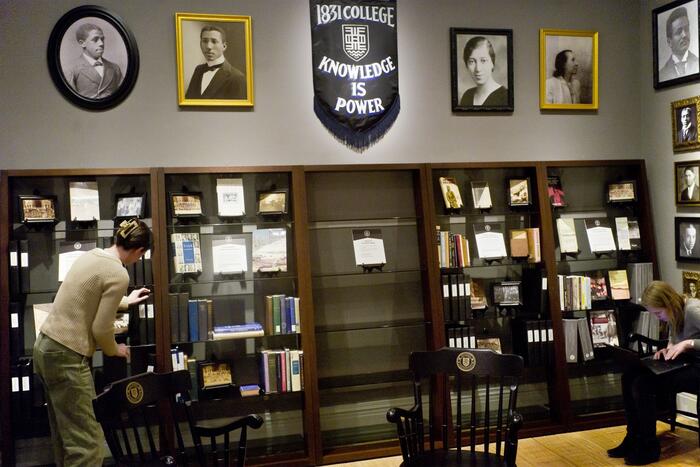

The exhibition’s greatest resurrection of memory lies just off the rotunda space, in a small adjacent gallery that has been transformed into the reading room of the so-called 1831 College. This college for Black men was proposed for New Haven that year, three decades before the start of the Civil War. It is tantalizing to consider the effect such an institution might have had on the discussion about slavery and white supremacy in those intervening years. It would have been the country’s first HBCU. But the idea was killed in its cradle.

At the concept’s announcement, New Haven Mayor (and Yale graduate) Dennis Kimberly convened an alarmed meeting of the city’s prominent white property owners. Yale alumnus Ralph Issacs Ingersoll, a congressman whose portrait hangs in the New Haven Museum, and attorney David Daggett, co-founder of Yale Law School, led the opposition to the college. The meeting voted 700 to four against permitting the college in New Haven. A subsequent court ruling written by Daggett against the establishment of Black schools in Connecticut was later cited in the Dred Scott decision.

To honor this institution that never was, Morand’s team imagined a library reading room in what they generically denominate as the “1831 College.” It includes a bookshelf of texts written by Black authors of Yale and New Haven, and leaves one bookshelf empty, in remembrance of the unwritten books that might have been produced by the college’s graduates. Around a table are five black wooden Hitchcock chairs, the kind common in Ivy League dorms and offices. They bear the “seal” of the college, a circular field ringed by the college’s name, oak leaves of wisdom and strength, acorns of possibility, and the “Knowledge is Power” motto. A center shield has waves representing the New Haven harbor site proposed for the college and the transatlantic slave trade, and the Akan symbol of knowledge from Ghana.

To honor this institution that never was, Morand’s team imagined a library reading room in what they generically denominate as the “1831 College.” It includes a bookshelf of texts written by Black authors of Yale and New Haven, and leaves one bookshelf empty, in remembrance of the unwritten books that might have been produced by the college’s graduates. Around a table are five black wooden Hitchcock chairs, the kind common in Ivy League dorms and offices. They bear the “seal” of the college, a circular field ringed by the college’s name, oak leaves of wisdom and strength, acorns of possibility, and the “Knowledge is Power” motto. A center shield has waves representing the New Haven harbor site proposed for the college and the transatlantic slave trade, and the Akan symbol of knowledge from Ghana.

But perhaps the most affecting element of the installation is the collection of some five dozen photographs of early Black Yale students and graduates that crowd the walls of the imagined library. As arranged and catalogued by the Beinecke’s Jennifer Coggins and Tubyez Cropper, the antique, sometimes imperfect portraits stir the imagination. These men and women, in overcoming the bigotry, discrimination, and white complacency of their day, convey and fulfill all the nascent promise of the 1831 College .

As stained windows once taught Bible stories to those who could not read, so this exhibition will reach museum goers, including schoolchildren, who might never find their way to a copy of Yale and Slavery. To stand in the gallery of the 1831 College, in communion with so many solemn and noble faces, is not simply to encounter the lessons of history, but to be absorbed and altered by them.

Morand agrees. “That room is a balm in Gilead,” he said—a spiritual medicine. “My hope is it will be a source of celebration in the midst of a very tough story and exhibition.”

In the conversation below, Morand speaks about his earliest consciousness of racial injustice, his experience at Yale Divinity School, and the “ubiquity of Black presence” in early New Haven. The interview was recorded in February and has been edited for clarity and length.

Timothy Cahill: What was your first awareness of race and racism?

Michael Morand: I was born in Covington, in northern Kentucky, where all my family roots are. I grew up just over the Ohio River, outside of Cincinnati. I’m a graduate of St. Xavier High School in Cincinnati, the same Jesuit high school my father went to.

A Jesuit high school—safe, then, to assume you grew up in a Catholic household?

If I tell you my father’s name is Joseph Francis Xavier Morand, and my mother, before she married my father, was in the convent, that might give it away.

Along with the other schools of the Society of Jesus, the motto of mine was “Men for Others.” My own growing-up in that life was very much informed by faith, and the belief that faith without works is dead. So, faith very much embodied in and engaged with the world. My consciousness came in high school, when I came to a recognition that I lived in a segregated neighborhood, and that of the 325 students in my high-school class, only one was Black. And also in work that I did outside of school, in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati, which was a very extensive and interesting place of very low income. Actually, I’m going to use the Barber formulation [Rev. William Barber, Director of the Center for Public Theology and Public Policy at YDS]—very “low-wealth” white Americans and Black Americans. It was and still is a very interesting neighborhood, one of the few broadly mixed Black and white “ghettos,” for lack of a better word, in the country. It had a lot of people who were Great Migration folks, Black Americans from the South and white Americans from Appalachia. A tale of two cities—Over-the-Rhine stood in stark contrast to my school and the segregated neighborhood I lived in. So, the consciousness was there.

What do you think was the seed of your teen-age sensitivity to these issues?

If you’ve got eyes, you see that where you live is a hundred percent white people.

I’d guess that a great many of the people in your high school didn’t have those eyes.

No, I think most white people actually recognize this. Whether we act on it or not is another matter.

I don’t know. The present evidence, the polarization of the conversation on race in this country, suggests the opposite.

People know that segregation exists, because you can’t not, but what they do with that knowledge or how they understand it differs. There are people who might ignore it or say that’s just the way it is. In the old days, it was God’s order, right? We live with these legacies of Christian apologetics for racism, of one group having power and even ownership over another group. I think the question is not necessarily the consciousness of racism itself, but how one understands it, analyzes it, and whether one chooses to deal with it as something that could and should and needs to be changed.

And you brought this awareness with you to Yale College. What year did you arrive?

In 1983. I came with this consciousness about inequality and a growing consciousness of white supremacy and racism in our country. It was not as activated, but I came with it. And at Yale, I quickly understood that Connecticut was not a land of perfection and heaven on earth, not a multi-racial paradise. I had a false sense coming to New Haven and Connecticut that it would be this progressive, integrated place. In fact, from a residential standpoint racial segregation in Connecticut is as severe as it is anywhere else, and in some ways more severe in income inequality.

As an undergraduate, I got involved in campus life and New Haven life in solidarity work—in labor organizing and global solidarity and anti-apartheid. And we all had a clear understanding that you couldn’t stand against racism and white supremacy in another place—i.e., South Africa—without also reckoning with the same issues in our local campus and community. I got to know a lot of people throughout Yale and New Haven and decided to stay here after I graduated. I worked for two years in the Chaplain’s Office and Dwight Hall. I went to Yale Divinity School in 1989, which was also the year I was elected to the New Haven Board of Alders. I like to say I took Yale’s mission of “service to Church and State” literally and took the and as a command to do both, to study ministry and theology as well as serve on the city council. After I graduated from divinity school, I went to work for the university administration doing community engagement.

What sent you to YDS for the Master of Divinity?

I was considering Congregational ministry in discernment. I was inspired by work that I had been doing in local activities, a community soup kitchen, solidarity work. So many of the people I got to know, people who were deeply rooted and committed, came from faith traditions of various sorts.

I was at home in the Congregational Church at the time I pursued ministry, but it became clear that, while I loved the Church, it really was not my one true home. Ministry in the Congregational Church, formal ministry, is pretty much parish ministry, and my own interests were never to be a parish minister or pastor. So, it was clear to me that that really wasn’t my path. And part of my discernment was knowing that ministry and faith can be expressed in multiple ways. I found that my ministry, such as it is, was in university administration and now, working in the literal heart of the university, as it says on Sterling Memorial Library, being part of Yale Library and particularly at Beinecke Library.

And YDS was a good place to be because of the ways it engages with the world. The preaching skills that David Bartlett taught me, those kind of communication skills, are useful in many different formats. Hermeneutics and other scholarly close reading are valuable not only for knowing sacred texts, but other texts as well. And I was blessed at YDS to do my supervised ministries with my longtime friend, the Reverend Samuel N. Slie. I’d known Sam through the Church of Christ in Yale and Dwight Hall, and with my husband, continued to know him throughout his life. He helped introduce me to New Haven history, to the embodied struggle and persistence and excellence and achievement in Black New Haven, in the Black church. Sam was one of the great alums of YDS. He was a son of Dixwell Church and connected me to its people and incredibly vital role in the history of YDS and Yale over two centuries. Among the many, many great things that YDS gave to me was to extend and deepen the relationship I had with fellow alum Sam Slie.

How long have you been at the Beinecke?

Since September 2016. So, seven and a half years.

And your expertise is in communications as opposed to library science?

Yes. I’ve always loved books and libraries. In addition to shouting out Sam Slie as a formative influence, I’ll give due homage and credit to the public libraries I grew up with. There was the world and it was free. The public library was an incredible catalyst and cupboard of ingredients for me to cook a life.

So, early on in my time here I got to know the New Haven Free Public Library. When I was an alder, I served two terms on the board of directors of the public library. It was only later that I realized there are jobs for people who are not just librarians and trained in library science. I jumped at the chance to work at the Beinecke, which is such an extraordinary place, and an expression of everything I’m interested in.

And now it’s led you to this opportunity, curating the exhibition, but more importantly, being part of a team correcting the omissions of Yale’s and New Haven’s history. I like the way the exhibition’s title, “Casting light on truth,” plays on the university’s motto, Lux et veritas.

You know, one of the questions people often asked during the research process was, “What surprised you about this work?” And the answer is, the ubiquity of it all. The ubiquity of slavery in the colonial and early republic context, the ubiquity of the economic ties of commerce with the West Indies in Connecticut, New Haven, and Yale. Likewise, the extraordinary ubiquity of Black presence and contributions, including free Black people. It is this ubiquity, the extraordinary community and network of Black people, that in some ways is the story. It’s those people who were always central but had been ignored or forgotten. If we ask, “What was ‘Black space’ in New Haven?”—we’re using the exhibition, the museum, and the 1831 College gallery to say that every space was Black space. There wasn’t a space, almost from the first days of English colonial settlers, where there were not Black people living, working, worshiping. Understanding that is at the center of the book and the exhibition.

You know, one of the questions people often asked during the research process was, “What surprised you about this work?” And the answer is, the ubiquity of it all. The ubiquity of slavery in the colonial and early republic context, the ubiquity of the economic ties of commerce with the West Indies in Connecticut, New Haven, and Yale. Likewise, the extraordinary ubiquity of Black presence and contributions, including free Black people. It is this ubiquity, the extraordinary community and network of Black people, that in some ways is the story. It’s those people who were always central but had been ignored or forgotten. If we ask, “What was ‘Black space’ in New Haven?”—we’re using the exhibition, the museum, and the 1831 College gallery to say that every space was Black space. There wasn’t a space, almost from the first days of English colonial settlers, where there were not Black people living, working, worshiping. Understanding that is at the center of the book and the exhibition.

I’m Chair of the Friends of the Grove Street Cemetery. When the cemetery was first opened in 1797, there was a segregated area for the burial of people of color, many of whom we showcase in the show. It was off to the side, in the least-status part of the cemetery. But as the cemetery grew and changed over time—that segregated area is now the first thing people see, immediately to the left of the gatehouse when you enter. So, the most prominent part now is what had been shunted aside. Within our tradition of both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament—and, if I may, the scripture of Robert Nesta Marley—the stone that the builder rejected becomes the chief cornerstone. And that in some ways is what this work is about. Making that ubiquity and centrality and cornerstone reality stand out in how we display things and bring people together.

One doesn’t often hear Bob Marley’s name given so complete, so thanks.

Well, yes. He was part of a religion, so he was a sacred singer.

——

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. is a writer specializing in religion and the arts.