By Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div.

Fifty-seven years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, a new generation gathered at the Lincoln Memorial calling for racial equality and justice reform. Wearing masks in the stifling August heat, the protesters listened intently as Dr. W. Franklyn Richardson ‘90 M.A.R. made an impassioned plea to keep working on the dream:

“We must stand up, we must fight, we must engage in every resource that we have,” he declared. “We still believe in America’s promise. Not only are we on the precipice of perishing, but we are on the precipice of realizing the promise.”

“We must stand up, we must fight, we must engage in every resource that we have,” he declared. “We still believe in America’s promise. Not only are we on the precipice of perishing, but we are on the precipice of realizing the promise.”

The march—called the Commitment March: Get Your Knee Off Our Necks—was planned by the National Action Network (NAN). Founded by the Rev. Al Sharpton, NAN is a civil rights organization in the spirit of Dr. King. Richardson has served as NAN’s board chair for the past 15 years.

“I became chairman at a very critical crossroads,” Richardson said. “NAN was a grassroots organization transitioning into an institution. We’ve been building a structure that will hopefully continue beyond us.”

***

W. Franklyn Richardson speaking at the Commitment March: Watch the video.

***

Sharpton is grateful for Richardson’s work as the leader of NAN and Chair of the Board of the Conference of National Black Churches, and the two have become close friends.

“He connects so well to people because his theology is fighting for the underprivileged—the antithesis of prosperity preachers,” Sharpton said.

Both Sharpton and Richardson were pleased with the outcome of the march. “There were no fights, no arrests, and no uptick in COVID,” Richardson said. “In the spirit of King, it was nonviolent. We put our hands together to steer our country back on track.”

Early challenges

Growing up with an undiagnosed reading disability in West Philadelphia, Richardson struggled in school and could not have envisioned the amazing twists and turns his life would take.

“When I graduated from high school in 1966, I couldn’t read,” he said. “Many schools in the inner city did social promotion. So if you don’t get the skills, you still passed to the next grade.”

Richardson faced other challenges as well.

“My elementary school was in the heart of a gang area,” he said. “My parents kept me out of gangs by immersing me in the life of the church.”

Richardson found another passion when, in high school, he got a job at a local hospital.

“I worked in the lab with tissue and blood samples,” he said. “It made me think deeply about humanity. I wanted to become a doctor.”

When Richardson told his high school counselor about his plans, he was told he was not college material.

“I was devastated,” Richardson said. “I wasn’t college material because the schools had not prepared me to be college material.”

But something else happened at this time that would change the course of Richardson’s life. He was stricken with appendicitis, and complications during surgery left him paralyzed for three days. While paralyzed, he “prayed to God and promised to become a minister” if healed.

Richardson did heal, and shortly thereafter, he enrolled at Virginia Union University, an HBCU that nurtures and trains Black preachers. He was accepted with conditional matriculation. Once there, he finally received help for his literacy issues. He majored in sociology and urban planning, with a minor in religion.

“Virginia Union shaped me,” he said. “I never knew a Black doctor or a Black teacher, so I never had an affirmation of identity in authority figures. It was an institution run by Black people. I was introduced to the Black elite. That was my trigger to move forward.”

Today, he is the Chairman of the Board of Virginia Union. “I went from conditional matriculation to signing the diplomas,” he said. “I am an example of how powerful a good education can be.”

A social justice preacher

Richardson proved to be such a natural talent that he received requests to preach while still in college.

“I got an invitation to pastor a church in Richmond when I was only nineteen,” he said. “I found myself pastoring in a depressed community struggling with urban renewal. We fought to make sure people were not mistreated. I always had a big social justice aspect to my ministry.”

After eight years of pastoring in Virginia, Richardson was asked to pastor Grace Baptist Church in Mount Vernon, N.Y. Located in Westchester County, Mount Vernon borders the Bronx to the south and Yonkers to the north.

After eight years of pastoring in Virginia, Richardson was asked to pastor Grace Baptist Church in Mount Vernon, N.Y. Located in Westchester County, Mount Vernon borders the Bronx to the south and Yonkers to the north.

“It was a depressed and divided community,” he said. “There was the south of the tracks and the north of the tracks. Most Blacks lived on the south.”

Richardson began to work on social justice issues. His first goal was to inspire the community to vote.

“Black people didn’t vote in school board elections and let the white community have their ways,” he said. “Because of that, all of the administrators and teachers were white, and all the students were Black.”

Richardson motivated parents to take ownership of their children’s future.

“I told them that their children were being underserved,” he said. “I am an example of that. When you fail to provide an education, you prepare people to be failures in society.”

Dr. Vivien Salmon came to Grace Baptist right when Richardson arrived. She was one of the first students to receive an academic scholarship from the church.

“He is an outstanding man,” Salmon said of Richardson. “He has provided our community with a sense of strength and stability. He understood that we had to move the agenda forward to maintain ourselves in the community as far as social justice and politics were concerned.”

Salmon was also touched by Richardson’s support of women.

“He let us know that women were at the forefront of the church,” she said. “Overall, he wanted to make sure we had a broad understanding of the civil rights movement. We stand for what is right in our community.”

Salmon is now the treasurer and trustee of the church and has a Ph.D. in healthcare administration. Richardson has helped her through this difficult time.

“I lean on my pastor for advice and comfort every day,” she said. “He has been a comforting voice to all our church members.”

Along with education, Richardson has also fought hard on housing issues. The church has partnered with a developer and the government to build over 400 units of affordable housing, including housing for seniors and young people.

Life at Yale

Richardson first came to Yale Divinity School for the 1975 Lyman Beecher Lectures, when famed preacher Gardner Taylor spoke.

“He was a great artist of preaching,” Richardson said. “He had a poetic approach.”

After watching Taylor’s lectures, Richardson wanted to go to Yale Divinity School. Taylor wrote him a letter of recommendation.

“YDS really affected my life,” Richardson said. “It sharpened my interpretive skills and my biblical background.”

Richardson is especially grateful for his New Testament professor, Dr. Abraham Malherbe.

“He was a white man from South Africa,” he said. “He gave me a new approach to the New Testament that I did not have. He unlocked all of the dynamics in the text. He had a warmness about him that moved me.”

Richardson was not bothered that his professor was a white man from South Africa; in fact, he invited him to preach at his church.

“He preached at Grace, and it was wonderful,” he said.

Looking back and looking ahead

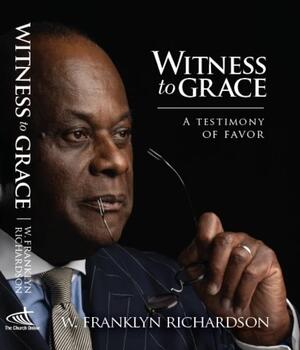

Richardson recently wrote a book about his remarkable life titled Witness to Grace: A Testimony of Favor. Sharpton was moved while reading his friend’s book.

“Richardson’s story is different,” Sharpton said. “Unlike most major ministers in the Black church, he did not inherit his pulpit; instead, he broke through and pastors one of the major churches in the suburban, middle-class Black area in Mount Vernon, which was unlikely for a boy growing up in Philadelphia.”

“Richardson’s story is different,” Sharpton said. “Unlike most major ministers in the Black church, he did not inherit his pulpit; instead, he broke through and pastors one of the major churches in the suburban, middle-class Black area in Mount Vernon, which was unlikely for a boy growing up in Philadelphia.”

Sharpton believes that Richardson’s unlikely rise is part of their connection to each other and to the next generation of activists.

“I have had a similar background to him,” Sharpton said. “We came from the bottom up and had to deal with racism in general, and classism in the Black community. Our lives match the young people today who come from similar backgrounds, and I think this type of connection is God’s way of using us in this difficult time.”

Richardson agrees. At 70 years old, he is working overtime to get out the vote and believes the current challenges “are an opportunity to see the grace of God.”

“The grace of God does not come in the conformity of our expectations,” he said while leaning forward in his desk chair. “This pandemic has shown the great inequities within our society and the misuse of the environment. It teaches us to approach life with a sense of sacredness. It is raising societal consciousness, and I think we are going to be a better people and a better country because of it. Could this be the intervention of God’s grace?”

——

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.

Lauren Yanks ‘19 M.Div. is a writer and professor and Executive Director of the Blue Butterfly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that helps educate women and children who have been trafficked and enslaved.