By Moses N. Moore ’77 M.Div.

As faculty, students, alumni/ae, and friends of Yale Divinity School reflect on the challenges posed by COVID-19, we can gain insight from the efforts of Orishatukeh Faduma 1894 B.D. to assist the residents of Sierra Leone, who taxed their diverse religious beliefs and rituals to make sense of the ravages of the 1918 flu pandemic.

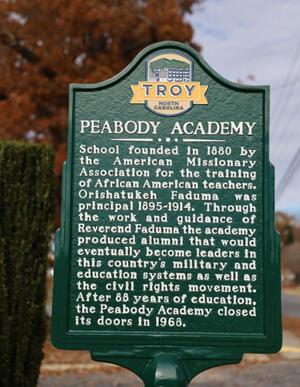

The relationship of Yale Divinity School with Sierra Leone, the-then British colony on the West Coast of Africa, dates from the famed Amistad Incident of 1839. In response to the Amistad captives’ imprisonment and trial for “mutiny,” YDS faculty and students assisted them in winning their freedom and returning to Africa. This historic intersection of abolitionism and evangelicalism contributed to the establishment of the Mendi Mission in Sierra Leone in 1841 and the founding of the American Missionary Association in 1846.

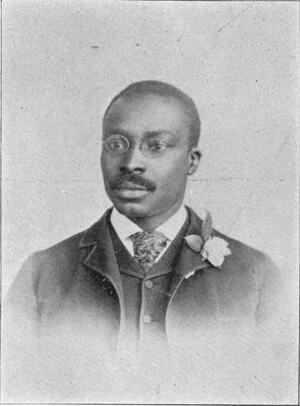

The ties between YDS and Sierra Leone continued via missionary activism and the subsequent enrollment of several students from the African country. One of these students was Orishatukeh Faduma, who was born on September 15, 1857, to West African parents freed by the British anti-slave squadron and transported as “indentured servants” to British Guyana. In keeping with accepted missionary custom, which required a “Christian name,” his newly converted parents christened their new son William J. Davis.

The ties between YDS and Sierra Leone continued via missionary activism and the subsequent enrollment of several students from the African country. One of these students was Orishatukeh Faduma, who was born on September 15, 1857, to West African parents freed by the British anti-slave squadron and transported as “indentured servants” to British Guyana. In keeping with accepted missionary custom, which required a “Christian name,” his newly converted parents christened their new son William J. Davis.

Repatriated with his family to West Africa at the age of eight, the intellectually precocious youth concluded his primary studies in the village of Waterloo and moved to Freetown—”the Athens of West Africa”—where he joined other students at Wesleyan Boys High School. Upon completing his studies there, Davis traveled to Britain and attended Wesley College and the University of London. The former was a traditional Methodist denominational school. However, the University of London had been established in the 1820s as a secular institution, and it reflected the changes being induced within the British academy by the scientific, intellectual, and academic currents emerging under the press of modernity. “Imbued with the modern spirit,” it provided Davis the benefits of a curriculum rooted more in the “new science than in the old humanities.”

Hailed as the first West African to “successfully pass the intermediate B.A. at London University” on his return to Sierra Leone in 1885, Davis joined the faculty of Boys High School, where he distinguished himself as a gifted teacher and cultural activist. On August 5, 1887, in accord with the goals of a religious and cultural reform movement inspired by noted educator, religious scholar, and Pan-Africanist Edward Blyden, he announced his change of name from William J. Davis to the “purely native name Orishatukeh Faduma.”

“Protestant Liberalism”

Amid simmering controversy related to his alleged rejection of his Christian name and its replacement with a “pagan name,” Faduma traveled to the United States and in 1891 became a student at Yale Divinity School. It was an auspicious time to enroll, since the Divinity School was one of the premier outposts of the era’s new theological synthesis referred to as “Protestant Liberalism.” The theological transformation at the Divinity School was accompanied by a progressive curriculum that also sought reconciliation of the tenets of evangelical Christianity with the scientific, intellectual, and religious currents emerging during late-Victorian modernity. Thus, Faduma and his fellow students were shaped theologically and academically by the theoretical and methodological assumptions of evolutionary theory and comparative religion, historical and biblical criticism, philosophy of religion, sociology, the science of missions, and social ethics.

Faduma’s mastery of the YDS curriculum was not only noted by faculty but also celebrated by Black classmates such as Hugh Henry Proctor, who exclaimed: “[A]lthough his [Faduma’s] parents were natives taken right from the bush, he was one of the brightest men in the class of over thirty coming from the picked universities of the world. He upset all the theories of the phrenologists and ethnologists.” His academic success was also attested by his graduation in 1894 with “honors,” and the publication of several articles that had their origins as student papers at the Divinity School. These bore such titles as “Materials for the Study of World Religions” (1896), “Africa or the Dark Continent” (1893), “Religious Beliefs of the Yoruba People of West Africa” (1895), “Success and Drawbacks of Missionary Work in Africa by an Eye-Witness” (1896), and “The Pastoral Epistles” (1894).

Virulent racism

By 1912 a despondent Faduma was convinced that the New Theology was not equal to the task of countering the South’s resurgence of virulent racism. “In the United States,” he lamented, “Anglo-Saxon teaching on race ideals is that all race varieties other than his are inherently inferior and dependent … In state, church, and society, the idea is put into practical operation in such a way that the best in the Negro is treated as filthy rags. In the Southern states particularly, the idea is enforced by means of the argumentum baculum—brute force—and all kinds of class legislation which the imagination can devise.”

Seeking respite from the debilitating physical and spiritual brutality of American racism, Faduma joined the Back-to-Africa Movement of Chief Alfred Sam. Having long shared Edward Blyden’s dream of a selective Black return to Africa, he became an enthusiastic and vital recruit of this Pan-African-oriented commercial, missionary, and emigrationist venture, which foreshadowed the more widely known movement later founded by Marcus Garvey. While the Gold Coast-born Sam was the self-styled and popularly acclaimed “Moses” of this intended exodus, Faduma became its most important ideologue and theologue. In numerous articles, he provided the American and West African press with the genesis, history, and goals of the movement.

Despite significant opposition in the United States and the active antagonism of the British Colonial Office, which sought to “nip the movement in the bud” and labeled “the whole thing a fraud,” the movement succeeded in purchasing a ship. Christened the S.S. Liberia amid appropriate fanfare, it set sail on July 3, 1914, for West Africa with Sam, Faduma, and approximately 60 delegates. However, British opposition became more aggressive as the S.S. Liberia approached the West Coast of Africa. It was seized by the British authorities, who disingenuously explained the seizure as a “war precaution” made necessary by the presence aboard the Liberia of a German-made wireless. Although British authorities subsequently released the Liberia, its unjustified detention fatally crippled the African Movement.

Upon the collapse of the African Movement, most of the delegates made an ignominious return to the United States. Faduma, however, resettled in Sierra Leone, where over the next eight years he made major contributions to educational, religious, and political developments in the colony and wider British West Africa. He served as principal of the United Methodist Church Collegiate School, member of the colony’s Education Committee, Inspector of Schools, tutor of teacher training, and officer in charge of the colony’s model school. In each of these positions and in multiple related addresses and articles on education and educational theory, Faduma advocated pedagogical and theological reforms that adapted African education to the era’s new scientific and intellectual developments while retaining a sensitivity to indigenous history and culture.

Science and religion

Faduma’s pedagogy was engrained with his theologically rooted belief in the complementary nature of science and religion. In contrast to religious conservatives and fundamentalists who regarded science as “antagonistic to religion,” he argued that “true science” and “true religion” could never be in opposition. “Seeming conflict between them,” he asserted, “is a conflict between the old theology and the new—a conflict between the old systems of thought and the new.” Faduma drew upon these intersecting theological and pedagogical convictions as he joined the increasingly desperate efforts of Sierra Leone’s religious leaders to mitigate and make sense of the deadly ferocity unexpectedly visited upon the west African colony in 1918 by the “Spanish Flu.”

Sierra Leone’s experience as an epicenter of the pandemic was rooted in the logistics of war that made the British colony’s deep-water harbors especially valued and frequently used sites for refueling ships traveling to and from Europe. On August 15, the H.M.S. Mantua arrived for refueling with a crew already suffering from influenza, and the virus was passed to the African laborers who refilled its coal bins. They carried the virus with them as they returned to their homes and neighborhoods, and speedily it began to burn through the colony’s residents. With the arrival and departure of other ships throughout the remainder of August, the deadly reach of the influenza was exponentially expanded.

Sierra Leone’s experience as an epicenter of the pandemic was rooted in the logistics of war that made the British colony’s deep-water harbors especially valued and frequently used sites for refueling ships traveling to and from Europe. On August 15, the H.M.S. Mantua arrived for refueling with a crew already suffering from influenza, and the virus was passed to the African laborers who refilled its coal bins. They carried the virus with them as they returned to their homes and neighborhoods, and speedily it began to burn through the colony’s residents. With the arrival and departure of other ships throughout the remainder of August, the deadly reach of the influenza was exponentially expanded.

The Sierra Leone Weekly News provided a poignant chronicle of the virus’ progress. By early September, it announced in alarmist tones that “the whole of Freetown lies at present under the shadow of a great anxiety due to the outbreak of a rather strange epidemic.” Adjacent to increasingly long columns listing the names of those who had succumbed to the virus, the paper reported that “doctors are at present flabbergasted”. As a result of their apparent failure, “the bulk of the people are left to take care of themselves and all sorts of remedies –from tea bush to peppers—are being tried.” Seeking to provide some relief from the “anguish and torturing,” the paper even shared recipes of hopeful remedies and reported that the populace had “been steadily drinking these homebrews, with something like religious fervor.”

“A Spiritual Side to the Present Distress”

The editor’s reference to “religion” and observation that “some amongst us are of the opinion that there is a spiritual side to the present distress” illuminated another critical aspect of the response of Sierra Leone’s population to the pandemic. Cataclysmic and apocalyptic events associated with war, disease, and other calamities have from time immemorial challenged, tested, and tempered the beliefs and rituals of the faithful. It was no different in Sierra Leone in the early fall of 1918. Members of its diverse religious community made up of adherents of African indigenous traditions, devotees of Islam, and members of multiple denominations of Christians initially sought relief from their visitations of suffering with renewed commitments to their respective religious beliefs and the employment of “protective” rituals, charms, beads, and amulets. Some explained the spreading pestilence as a sign of divine or ancestral wrath for sins of commission or omission and made haste to mend their ways by improving their religious conduct or honoring their ancestors more fully. Others viewed it as evidence that their existing religion and religious rituals had been proved ineffective by the relentless efficiency of the pandemic. In the wake of the latter conclusion was “a flurry of conversions to Christianity or Islam by traditional believers or of reversions from Christianity and Islam back to traditional beliefs.”

In a letter published in the Weekly News, “J,” a resident of Sierra Leone, expressed the alarm of many traditional adherents of Christianity with his proclamation that “everyone seems baffled and overwhelmed and is led to question the Providence of God.” To console and encourage the faithful, he cited biblical events and scripture as he confessed that he still dared “to believe that the hand of Providence is in it all and is creating a new consciousness in us of His ever-abiding presence in all our human affairs and causing us to recognize Him in our life’s destiny.” Having discerned God’s “wise and inscrutable Providence” at work even amid the suffering accompanying the pandemic, he admonished: “Now fellow sinners and sufferers let us take our stand here and ask God for mercy, pardon, and forgiveness.”

Notwithstanding efforts of various segments of Sierra Leone’s diverse religious communities to explain, justify, and mitigate its effect, the pandemic continued its apparent indiscriminate winnowing of young and old, male and female, Black and White, good and bad from the ranks of Indigionists, Muslims, and Christians.

A measure of solace

As the list of Sierra Leone’s dead increased exponentially, Faduma joined the desperate discourse among the colony’s secular and religious leaders. An evangelical liberal, he provided a distinctively different perspective as he engaged the theological, philosophical, pedagogical, scientific, and medical challenges posed by the pandemic. In his attempt to offer some measure of solace to members of the Christian community who found their traditional theological beliefs and religious rituals of little comfort, Faduma evoked tenets and insights gleaned from his studies at YDS. Explicitly rejected were what he labeled traditional Protestant “superstitions” that taught that “sin is the cause of pain and suffering” and that the epidemic was, therefore, a divine winnowing of Sierra Leone’s “saints” and “sinners.” It was not true, he insisted, “that those who escaped the dire effects of the epidemic in our land are the only saints, while those who do not are the sinners.”

Faduma also evoked Protestant Liberalism’s emphasis on human ability and responsibility rather than providential determinism as he opined that the “lessons to be learned from the epidemic were not about humanity’s sinfulness, nor God’s wrathful judgment and complicity in their suffering,” but rather about social responsibility and the “workings of physical laws” related to sanitary conditions. Insisting that faith and prayer without works were “of no avail,” he admonished that unless the lessons of health and sanitation were heeded, religious faith and ritual would do nothing for physical health: “[U]nless we repent and rectify these … we shall perish in spite of prayers and songs when the time of visitation comes.”

However, like other members of the faithful, Faduma did not prove immune to the more profound and challenging theological and soteriological questions elicited by the pandemic. In the aftermath of the misery and tragedy of the pandemic as well as the broader social and spiritual dislocations occasioned by the war, he revisited theological and soteriological concepts long held dear in a series of newspaper articles aptly titled “The Faith That Is in Me.” In this often-poignant series, Faduma presented a summary and analysis of the evolved theological convictions and beliefs that continued to shape his life and work. He sounded a new note of realism, which suggests that he was among the theological liberals who, amid the carnage of World War I, the pandemic, and theological liberalism’s manifest failure to usher in the “kingdom of God on Earth,” were forced to reexamine and temper their idealism and optimism.

Appraising Faduma

Despite the controversial nature of the theological, missiological, and pedagogical reflections and reforms advocated by Faduma, his numerous contributions to the religious, educational, and political well-being of Sierra Leone and broader West Africa were not unappreciated. In 1923, the Sierra Leone Weekly News published “an appraisement of Professor Faduma” that summarized and celebrated his contributions before, during, and after the pandemic. The paper’s tribute coincided with Faduma’s plans to return to the United States. On September 19, 1923, following a round of farewell services “in recognition of his valuable service to the Colony in Educational, Literary and Religious undertakings,” he sailed for the United States.

By December 1924, Faduma was re-associated with the American Missionary Association and stationed at Lincoln Academy in Kings Mountain, N.C. During the waning years of his life, which were spent in High Point, N.C., with his wife of almost 50 years, Faduma’s dogged evangelical liberalism was further assaulted by the brutalities of World War II and the continued intransigence of Southern racism. In a 1943 article entitled “Some of My Experiences in the Southland,” he poignantly recalled his experiences with racism during his 39-year ministry in the South, which he described as “a land of conundrums.”

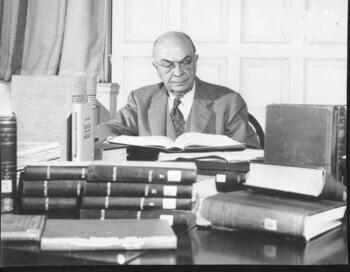

It was perhaps fitting that Faduma issued the final summaries of his life’s work in response to a 1944 alumni questionnaire from Yale Divinity School. Replying in an aged script, he reported that he was a “Retired Missionary” who had spent a total of “57” years at various mission posts and institutions in the United States and Sierra Leone. He also included a listing of 50 of his “literary contributions,” the typescript of his autobiographical sketch entitled “My Nigerian African Background,” and a copy of “Some of My Experiences in the Southland.”

Intrigued by the aged African alum, Dean Luther Allan Weigle requested additional information. In May 1945, Faduma replied in a letter that gave a more comprehensive account of his life and labors and even recounted his years as a student at the Divinity School. Explicitly recalling his old instructors, “Dean Day, Professors Fisher, Harris, Brastow, Stevens, Curtis, [and] Porter,” Faduma confessed that they “left behind them and in my life memories which are indelible.”

Weigle responded with a letter that expressed the Divinity School’s pride in Faduma’s accomplishments: “I congratulate you heartily upon the long and effective service that you have rendered in the field of Christian missions and Christian education, and I assure you that we of the faculty of your old school take pride in what you have accomplished.” Less than a year later, on January 25, 1946, Faduma died and was buried at High Point.

Weigle responded with a letter that expressed the Divinity School’s pride in Faduma’s accomplishments: “I congratulate you heartily upon the long and effective service that you have rendered in the field of Christian missions and Christian education, and I assure you that we of the faculty of your old school take pride in what you have accomplished.” Less than a year later, on January 25, 1946, Faduma died and was buried at High Point.

Faduma’s long career and contributions were testimony to the theological and pedagogical liberalism that was nurtured during his study at YDS and doggedly embraced even as it was chastened and tempered amid the relentless persistence of Southern racism, the wake of the brutality of two world wars, and the horror of the 1918 influenza pandemic, particularly as experienced firsthand among the residents of Sierra Leone.

Dr. Moses Moore ’77 M.Div. is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Arizona State University.