By Timothy Cahill ’16 M.A.R.

In the language of art, a shape is a two-dimensional outline of an area or figure. Circle, square, rectangle, triangle—take a line out for a walk, and these are the basics from which everything is drawn. As universal as these shapes are, though, it doesn’t take long to discover that they are limiting. They don’t get you far past stick figures or cartoons. To express life in its rich detail, you need modeling and perspective, techniques to indicate volume, dimension, mass, and proportion. Thus shapes become forms—sphere, cube, cylinder, cone—raw materials to render the complex world.

Learning to draw depends on crossing the frontier from shape to form. So too the art of understanding people. Like shapes, the labels we use to define others are two-dimensional. Black and white, gay and straight, young and old, Christian and Muslim. We can’t get far with them. Only when we begin to see with perspective and proportion can reality become rounded, complex, three-dimensional. Strangers become neighbors; the Other, a brother. It’s a necessary movement beyond the self to the world.

Learning to draw depends on crossing the frontier from shape to form. So too the art of understanding people. Like shapes, the labels we use to define others are two-dimensional. Black and white, gay and straight, young and old, Christian and Muslim. We can’t get far with them. Only when we begin to see with perspective and proportion can reality become rounded, complex, three-dimensional. Strangers become neighbors; the Other, a brother. It’s a necessary movement beyond the self to the world.

This is the subject of From Shape to Form, on display at Yale Divinity School until late June. On its face, the show appears to be a familiar exploration of “identity,” the concept encompassing the ways contemporary artists challenge cultural stereotypes and explore issues of gender, sexuality, race, heritage, and diversity. Curator Jon Seals ’15 M.A.R. declares this intention in the first sentence of the exhibition’s description. “From Shape to Form,” he writes, “highlights a selection of contemporary Latinx artists working through varied materials and processes to explore a range of topics including communal/individual memory and progress/regress.”

The opportunity to hear the voices of underrepresented artists is, decidedly, one of the fruits of this collection of six emerging painters, sculptors, photographers, and mixed-media artists whose roots are in Latin America, from Mexico to Chile to Suriname.

But Seals’ ambitions for the exhibition run deeper. His curator’s statement continues, “From Shape to Form enters into conversation with these artists in rejecting flattened notions of sameness and difference. The art assembled here embraces a more nuanced and dimensional approach filled with depressions, reliefs, and fantastic textures.”

In this, Seals is describing more than surface smoothness and roughness, visual peaks and valleys. The “depressions, reliefs, and … textures” he alludes to are as psychological as they are formal, philosophical as much as physical. While revealing something of what it means to be Latinx in the United States, the show also meditates on what it means to be human in this place at this moment in history. The artworks are autobiographical, memoiristic, confessional, rich with childhood memories of family, faith, loss, migration, displacement, and fear.

The six artists represented are Gaby Collins-Fernandez, Xavier Robles de Medina, José Delgado Zúñiga, Saredt Franco, Rocío Olivares, and Carmen Flores. They live and work in the U.S., but were born south of the border upon which Donald Trump would build his wall. The dissonance created by Trump’s election incited Seals’ 2017 YDS exhibition, The Complexities of Unity. While he wants firmly to move this new exhibition beyond overt political readings, the curator allows that the President’s divisive presence ripples through these artworks as well.

As a Christian artist and educator, Seals struggles with much of Trump’s worldview. “We are called to serve the oppressed, the hungry, the needy, to include, to incorporate, to reach out, to share,” he says. A spirit of inclusivity guides From Shape to Form, and reflects Christian doctrines that guide us “to invest in the lives of others. That’s what Christ did. He saw the full person.”

Seals travelled from his home in Florida to YDS in early March to install the exhibition, where he worked with Assistant Curator Laura Worden ’19 M.A.R., an Institute of Sacred Music student in the fourth semester of an extended degree program in religion and visual culture. They moved artworks up and down the ramped corridors of the school’s north wing as they arranged the show.

Seals travelled from his home in Florida to YDS in early March to install the exhibition, where he worked with Assistant Curator Laura Worden ’19 M.A.R., an Institute of Sacred Music student in the fourth semester of an extended degree program in religion and visual culture. They moved artworks up and down the ramped corridors of the school’s north wing as they arranged the show.

The exhibition begins in the Sarah Smith gallery, just off the YDS main entrance, and holds the walls the length of the building. As it descends to the ISM, the work grows darker, moving from swirling relief sculptures and velvet abstractions to grim visions of mayhem and death.

“That needs to be shown,” Seals says of the unflinching memories of murder victims by Carmen Flores that conclude the exhibition. “This is an exploration of artists working though concepts and realities of their own lives. These are stories that need to be told.”

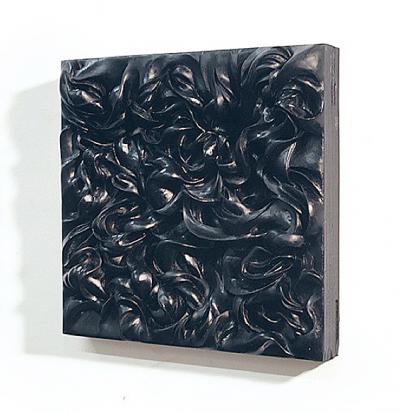

The starkness of Flores’ work, Seals notes, is counterbalanced by the light touch of Xavier Robles de Medina, a young sculptor from Paramiribo, Suriname, a former Dutch colony in South America. His polymer reliefs eddy, billow, and surge with luxuriant waves and curves. They look like flames, river rapids, even the stiff peaks of meringues. In fact, the sculptures are derived from the elaborate hairdos and hair-product ads Robles de Medina saw growing up around his mother’s beauty shop. He reinterprets the haute coiffure in polyurethane forms, casting abstractions he finishes with, among other tools, curved dental picks.

The starkness of Flores’ work, Seals notes, is counterbalanced by the light touch of Xavier Robles de Medina, a young sculptor from Paramiribo, Suriname, a former Dutch colony in South America. His polymer reliefs eddy, billow, and surge with luxuriant waves and curves. They look like flames, river rapids, even the stiff peaks of meringues. In fact, the sculptures are derived from the elaborate hairdos and hair-product ads Robles de Medina saw growing up around his mother’s beauty shop. He reinterprets the haute coiffure in polyurethane forms, casting abstractions he finishes with, among other tools, curved dental picks.

“I was presented with concepts of aesthetics at an early age,” he writes, referring not only to his mother, but to his dentist father and a grandfather who was an artist. “To me, all three professions involve a practical attitude toward personal aesthetics as well as varying degrees of conceptual engagement…. I transform [my] materials by caressing, massaging, pulling, and pushing skin-like surfaces and forms.”

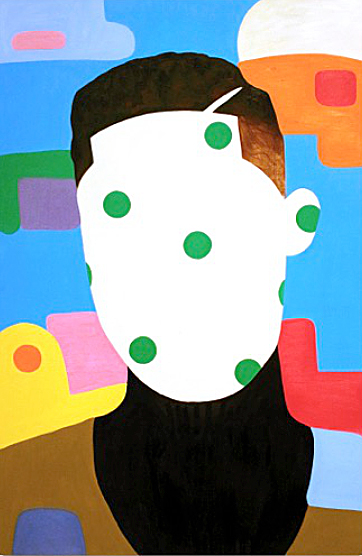

Stylized haircuts also inform the work of José Delgado Zúñiga, whose paintings appropriate the “lineups, tapers, and fades … popular among Latino men.” These hair fashions, he notes in his artist’s statement, “have enabled [young Latinos] to express themselves as an individual or as a collective.” In a pair of works titled Shapeless and Shape up, Delgado Zúñiga presents large, faceless portraits whose carefully trimmed hairlines assert themselves against vibrant decorative surfaces.

The painter names bilingualism, socio-political influences, and the musical and visual bricolage of his Mexican-American upbringing as source material. His consciousness was formed by “traces of the past that have been written and recorded in song, melody, and rhythms,” where “images invigorate me; color is the trace of my memory, the stream of sensation, feeling, experience, and gesture.” Delgado Zúñiga’s work crisscrosses between figure and ground, shape and form, style and self. His large collage, Frankenstein, casts a grotesque figure adrift in a cacophony of pattern and color—a metaphor, the artist observes, of the “negligence” of White America that “haunts our present.”

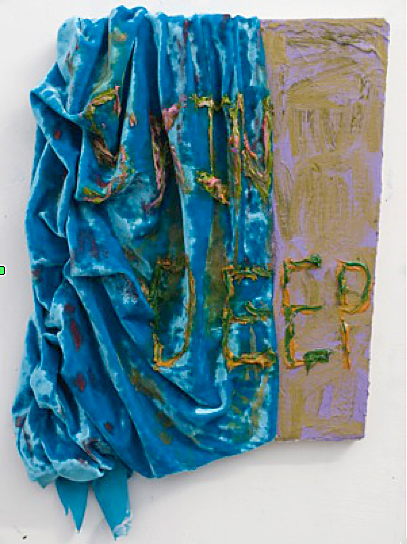

Gaby Collins-Fernandez M.F.A. 2012 studied painting and printmaking at Yale, where she developed an “interest in [the] intersection of material and image.” Her paintings are vivid, sometimes jolting in their chromatic juxtapositions, marked by her use of crushed velvet. Her Blue Velvet SKIN DEEP painting is typical. Its sheeny electric-blue fabric is gathered and draped on the frame like a half-skinned pelt, revealing part of a painted canvas below. Across the disrupted surface in capital letters read the words “SKIN DEEP.” Similar solid-cap inscriptions mark all the works, declaiming “MOM,” “YOU OR NOTHING,” “GENTLE TERROR”— fragments, the artist says, “overheard within the urban clutter and movement of New York.”

Gaby Collins-Fernandez M.F.A. 2012 studied painting and printmaking at Yale, where she developed an “interest in [the] intersection of material and image.” Her paintings are vivid, sometimes jolting in their chromatic juxtapositions, marked by her use of crushed velvet. Her Blue Velvet SKIN DEEP painting is typical. Its sheeny electric-blue fabric is gathered and draped on the frame like a half-skinned pelt, revealing part of a painted canvas below. Across the disrupted surface in capital letters read the words “SKIN DEEP.” Similar solid-cap inscriptions mark all the works, declaiming “MOM,” “YOU OR NOTHING,” “GENTLE TERROR”— fragments, the artist says, “overheard within the urban clutter and movement of New York.”

Saredt Franco has memories of going with her mother to Mass in a cathedral in Mexico City, where she lived until age 10, when the family moved to West Palm Beach, Florida. In her artist’s statement, she writes of herself in the third person: “Her interest in the political and the absurd originated from her own experience as an immigrant, constantly trying to reconcile two worlds, which were ever more parallel.”

A sense of straddling boundaries, of sitting between chairs, infuses her deadpan urban landscapes. There are walls, fences, rooftops, cemeteries. Her pictures appear empty at first, set pieces waiting for someone to appear. The absence quivers with a Waiting-for-Godot presence. In one photo, it’s the shade of whoever bashed the doorway-shaped opening in a cinderblock and razor-wire wall; in another, the soul who set up a white-draped altar before a brick wall. In a third, its whoever built the chain-link fence thinking they could confine the wandering clouds behind it.

A sense of straddling boundaries, of sitting between chairs, infuses her deadpan urban landscapes. There are walls, fences, rooftops, cemeteries. Her pictures appear empty at first, set pieces waiting for someone to appear. The absence quivers with a Waiting-for-Godot presence. In one photo, it’s the shade of whoever bashed the doorway-shaped opening in a cinderblock and razor-wire wall; in another, the soul who set up a white-draped altar before a brick wall. In a third, its whoever built the chain-link fence thinking they could confine the wandering clouds behind it.

Man proposes, God disposes, Franco exposes. The irony of her photos is leavened by a sense of desire, of a spirit striving to transcend physical limits. Her sensitivity to the symbolic potential of the world is a vestige of her religious childhood. “I think of Catholicism as an ethnicity more than a belief system,” she says, but its gravitas adheres.

“I grew up Mexican, so super-Catholic,” she said in an interview. “I feel that I cannot-not have symbols that mean a lot. I loved to go to church because it was this beautiful experience. The stained glass. The murals. For me, Catholicism [is] a visual language. My friends, my fellow-artists, when I went to school, just did not have that immediacy of symbolism and meaning.”

Rocío Olivares received her BFA from the Universidad Catholica de Chile in Santiago, Chile, then came to New York for an MFA at Columbia University. Layered meanings are the subject of her video, Cattle Egrets, a sly exercise in subverting surface expectations. The film, which plays in a loop with a second short video, appears at first to be a placid nature documentary about a heron-like bird. But it slowly comes unhinged as the content of the narration diverges from the subtitles that had originally matched it. Soon, the titles at the bottom of the screen are describing something banal—migratory habits, for example—while the voice-over grows ever more lurid, relating brutal acts of egret aggression against other birds, even their own chicks in the nest.

This all happens while you are dreamily distracted by footage of the handsome white birds with their dusky orange plumes. As you struggle to catch up with the text, disorientation renders the images all but impossible to focus on. The video has become a kind of anti-visual artifact, and you, no longer a viewer, the object of a savvy perceptual ambush on information, awareness, and the fragility of attention.

Carmen Flores’ biographical drawings have a similar element of ambush. Flores was born in Culiacan, capital of the Mexican state of Sinaloa, a place rampant with drug violence. Seals met her while both were MFA students at Savannah College of Art and Design, where, he recalls, “she had a gripping fear of being killed by a stray bullet.”

Carmen Flores’ biographical drawings have a similar element of ambush. Flores was born in Culiacan, capital of the Mexican state of Sinaloa, a place rampant with drug violence. Seals met her while both were MFA students at Savannah College of Art and Design, where, he recalls, “she had a gripping fear of being killed by a stray bullet.”

Flores’ large graphite and chalk narratives are elegies to the victims of violent death. They confront the viewer with horror, dread, and, ultimately, pathos. “I select incidents that shock me because of their brutality and/or impunity,” she writes. Bad Dream depicts a screaming girl waking from a nightmare; Portrait of 50 Missing Girls superimposes the faces of departed children like fugitive memories; Playing presents a grim tableau of a dog-pack nuzzling and chewing human body parts. Flores annotates her drawings with a form of embroidery called “redwork,” a red-thread technique typically found in folk patterns. She uses it to indicate gunshots, bullet wounds, life blood. Her Did not come back pays homage to souls lost to violence, while meditating on her own existential displacement and the meaning of her name. In the large wall sculpture, the dead are remembered in descending rows of snowy handkerchiefs embroidered with red floral blooms (flores is Spanish for flowers), each one bleeding a trail of carmine thread.

Carmen Flores reminds us that “shape” and “form” are also verbs, that what we experience shapes us, and that we are formed by what we make. The artists in From Shape to Form define themselves by themselves and by the world they inhabit. In the process, they leave their mark on us.

Timothy Cahill ‘16 M.A.R. writes on religion and art.